Kentucky senator looks to create a pathway to study ibogaine for the treatment of addiction

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

A Kentucky lawmaker plans to introduce a bill during the next legislative session to allow researchers to study an illegal psychedelic drug called ibogaine as a treatment for drug addiction, a condition that continues to plague the state.

Ibogaine is a naturally occurring compound found in the root bark of iboga, a West African shrub. It is illegal in the U.S., but is used in some other countries, including Mexico, to treat substance-use disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder and treatment-resistant depression.

“My hope is to create an avenue, or a pathway, where we can start doing some research on this preparation, on this compound here in the commonwealth as well,” said Sen. Donald Douglas, R-Nicholasville, noting earlier that Texas had already passed a bill to allow ibogaine research.

Douglas, who is also a physician, told the Aug. 27 Interim Joint Committee on Health Services that the hope is to also reclassify ibogaine. It is currently a Schedule 1 drug, which are drugs that have a high potential for abuse and no recognized medical purpose in the U.S. “Ibogaine is neither of those,” he said.

Douglas said too many Kentuckians are still dying from overdoses, even with the declines seen in the last three years. According to the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy, 1,410 Kentuckians died from a drug overdose in 2024.

Further, he said, despite having the greatest number of rehabilitation clinics for substance-use disorder in the nation, “real data” suggest that over 85% of the individuals who complete these programs relapse.

“I’m really here today to introduce a different clinical model. We’ve been dealing with the same clinical model over and over for decades. It ain’t working, folks. It’s not working,” Douglas said.

Dr. Jean Loftus, an ambassador for Americans for Ibogaine and a plastic surgeon, said the one-year success rate for traditional treatment is about 10%, even at the best recovery centers. With ibogaine, she said 23% to 50% remain abstinent at one year, and that’s without any other supports.

“We do not know what the numbers will be with support, but they’re expected to be even better,” she said.

Loftus stressed that ibogaine is not a cure for addiction, but instead stops withdrawal symptoms and cravings, “so that the addicted person can then remain abstinent.”

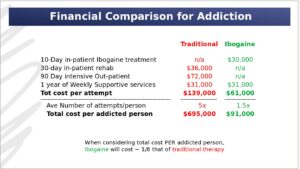

In addition to the human cost of addiction, Loftus said there is an economic impact to consider. When it comes to addiction, the total cost of traditional care per addicted person is nearly $700,000, and the total cost of an ibogaine treatment is $91,000, according to slides presented by Loftus.

“Ibogaine costs about one-eighth that of traditional treatment per person, and these numbers are for treatment attempts per person, not for treatment successes,” she said.

So far, no placebo-controlled, double-blind trials have been conducted on the use of ibogaine to treat substance-use disorder, which are needed for it to be approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration.

“We have plenty of evidence that ibogaine has helped many people overcome addiction, PTSD, treatment-resistant depression, including a high-level study by Stanford … ,” Loftus said. “But we do not yet have large prospective studies with effective long-term follow-up, nor do we have randomized line studies, which are the gold standard in clinical research.”

Loftus also noted that while it is known that ibogaine poses a risk of cardiac death for some people, she said, “Cardiac risk with ibogaine can be mitigated with magnesium monitoring and early intervention. And just to be clear, the FDA does not expect any drug to be 100% safe, because none are.”

Gov. Andy Beshear pointed to this risk when asked about ibogaine at an Aug. 28 news conference.

“A lot more research needs to be done on Ibogaine. It can also cause some really significant reactions in a number of people,” Beshear said. “You don’t tread lightly into something that could be that powerful or could potentially be that damaging. So this is what the FDA is for. This is what they ought to be researching.”

He also pointed to the success Kentucky had in decreasing its overdose deaths by 30% in 2024, noting that Kentucky already has treatments and systems that work.

“So let’s make sure that we’re not just looking at the next bright, shiny object, but that we’re recognizing the hard work with the structure we have in place, (which) has done so much to help our people, and let’s keep doing that work,” he said.

Douglas introduced a similar bill during the last legislative session, but said he withdrew it because of the time constraints of a short session, which lasts no more than 30 legislative days. “I will be reworking the bill,” he said.

Douglas said he had been in contact with legislators from up to 15 states who are willing to look at forming a “legislative consortium” to put money into research for ibogaine.

Asked by Chairman Stephen Meredith, R-Leitchfield, if the state’s research universities were interested in doing the research or if they had been consulted, Douglas said, “I haven’t reached out to them,” and then immediately moved on to talking about the need to look at “public-private partnerships.”

Loftus told KHN after the meeting that if Kentucky’s ibogaine research plan follows other states’ plans, like Texas, this research would be accomplished through a public-private partnership. This, she said, would allow the state to get money back from its own investment, once ibogaine becomes a treatment.

The idea to allow clinical trials on ibogaine as a treatment for addiction was originally proposed in Kentucky by the former Kentucky Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission director, Bryan Howard, who was appointed by then-Attorney General Daniel Cameron. Hubbard proposed that the commission commit $42 million of the opioid settlement money for such trials. Hubbard’s proposal was ultimately shut down by Attorney General Russell Coleman when he took over the commission.

Asked after the meeting if he would seek opioid settlement monies for this research, Douglas said he will have conversations about ibogaine with the attorney general, but because Coleman is in charge of that fund, “It really is the attorney general’s call.”

Loftus wasn’t so diplomatic, saying, ideally, it would be good to use about 5% of the opioid settlement funds for ibogaine research. This would amount to about $45 million at this time.

“Can that be done legislatively is another question, ” she said. “But ideally, that would be the route so that it doesn’t take taxpayer dollars.”

Hubbard, as the executive director for American Ibogaine Initiative, continues his work to get funding for FDA–approved clinical trials of ibogaine for the treatment of substance-use disorder. Most recently, he was the architect of the Texas legislation that earmarked $50 million in funding toward that effort in May, an amount to be matched by private sector investments, according to a story about Hubbard in the Lexington Herald-Leader.

Jessical Blackburn Allen, a licensed social worker and a volunteer with Americans for Ibogaine, said her struggles with substance use started when she was 17 and escalated into a daily oxycodone or heroin habit by the age of 19. She said she made five or six attempts to quit over five years, using FDA-approved medications, with no success. In 2008, she underwent an ibogaine treatment in Mexico and said the experience “saved my life.” She has been sober for 10 years.

“Because of ibogaine, I was able to reclaim my autonomy and make the conscious decision to make healthier choices and allow myself to heal and grow,” she said. “Every person who suffers should be afforded the same opportunity.”