Report: KY still pays price for one of nation’s highest rates of opioid use disorder

By Sarah Ladd

Kentucky Lantern

Kentuckians living with addiction can call Kentucky’s helpline at 833-859-4357. Narcan, which can help reverse overdoses, is available at pharmacies for sale and through some health departments and outreach programs for free.

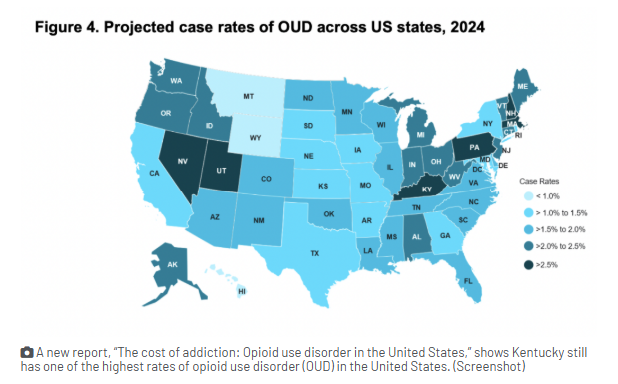

Even though overdose deaths have declined over the last three years, Kentucky still has one of the highest rates of opioid use disorder (OUD) in the United States, according to a national report released Tuesday.

“The cost of addiction: Opioid use disorder in the United States” shows Kentucky is one of four states where the rate of opioid use disorder is higher than 2.5% of the population aged 12 or older. The others are New Hampshire, Nevada and Massachusetts.

Margaret Scott, an author of the study from Avalere Health, said the estimate is based on the National Survey on Drug Use. The report doesn’t look at factors that might lead to higher or lower rates of cases.

“We did rely on the national figures from the national survey, but this is self-reported cases of opioid use disorder, so it is possible that individuals in those states are more likely to self-report,” she said.

In 2024, 1,410 Kentuckians died from an overdose, according to the 2024 Drug Overdose Fatality Report. In 2023, there were 1,984 overdose deaths, which was a decrease from the 2,135 lost in 2022.

“It is encouraging to see the number of overdose deaths decreasing,” Scott said. “We’re still seeing 80,000 overdose deaths in the country. It’s hard to say what is contributing to that decline (in Kentucky), but we do know that OUD is still a significant problem.”

Ben Mudd, the executive director of the Kentucky Pharmacists Association, said Kentucky does a lot right when it comes to diagnosing and treating addiction.

“There’s been a huge focus on harm reduction and naloxone distribution and I think that is why we’ve seen the decrease in overdose deaths,” Mudd told the Lantern.

But that intervention, which can reverse an overdose, “doesn’t necessarily stop new cases.”

“Those cases still exist,” Mudd said. “There’s so much naloxone out there, people are educated, perhaps people aren’t using alone, things like that. All of those programs that have been put in place have led to fewer overdoses, but not necessarily a reduced number of people with opioid use disorder.”

What does the report show?

Tuesday’s report is mostly interested in the costs surrounding OUD and the economic impact of addiction.

“Some of the costs that we estimated included things like lost income taxes based on the lost productivity for businesses as well as employees’ lost wages. We looked at property, client crime from OUD, as well as different types of costs to the state and local governments,” Scott said. “Those costs included things like Medicaid direct costs for substance use treatment, as well as those lost income taxes and corporate taxes, and then, of course, the criminal justice costs, which would include police presence, courts, jails, all of those things.”

In Kentucky, OUD costs big bucks, according to the report:

- Kentucky has one of the highest rates of opioid use disorder in the nation.

- Opioid use disorder costs Kentucky about $95 billion, with an average cost per case of $709,441.

- State and local governments bear more than $2 billion in costs, primarily driven by criminal justice expenses and lost tax revenue.

- The state/local per capita OUD cost is among the highest nationally, between $400-$500 per resident annually.

- OUD-related costs in Kentucky are more than 6% of the state’s gross domestic product.

“Our study shows that barriers to care include physician stigmatizing and expressing reluctance to treat OUD patients, inadequate provider education and training, geographic distances to treatment locations, and social stigma,” Scott said.

Medicine treatment pays off in the long run, the report says, as it “has been shown to reduce cravings, increase abstinence from opioids and reduce morbidity and mortality, thereby making it a key component for addressing the economic and public health consequences of OUD.”

Treatments can include medications and therapy. Methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone are treatments approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for OUD management.

“As states and local governments explore new strategies to reduce healthcare costs, encouraging public health, governments and payers to prioritize OUD treatments can lead to greater savings,” Michael Ciarametaro, managing director at Avalere Health, said in a statement.

This is especially true for the formerly incarcerated, who live “opioid naive” behind bars and may, upon release, take the same dose they did before being incarcerated and not have the resistance to handle it, Mudd explained.

“If you’re incarcerated, you hopefully don’t have access to opioids. But when you leave that facility, many folks go back to the same routine that they were in before, the same environment they were in before,” he said.

What is Kentucky doing to combat opioid use disorders?

Kentucky has taken aggressive steps to treat and prevent addiction. The latest Drug Overdose Fatality Report showed that for 2024:

- $29.8 million was distributed in grant and pass-through funding from the state Office of Drug Control Policy.

- 170,000 doses of Narcan were distributed.

- 84 syringe exchange program sites served 27,799 unique participants.

- 142,312 Kentuckians received addiction services through Medicaid.

- 17,399 Kentuckians received treatment paid by the Kentucky Opioid Response Effort.

- 17,984 Kentuckians received recovery services like housing assistance, employment services, transportation and basic needs services in their community, paid for by the Kentucky Opioid Response Effort.

- 3,329 incoming calls were made to the KY HELP Call Center with 14,087 outgoing follow-up calls.

- 21 counties are certified as Recovery Ready Communities, representing 1,495,518 Kentuckians.

There’s still some stigma when it comes to seeking treatment, Mudd said.

“There are folks, even within my profession, that think that this is just a pill mill,” Mudd said. A “constant turnover” of patients is a “real thing” and “a concern of health care providers across the state.”

“It’s the nature of addiction and folks with OUD,” he said. “It’s hard to differentiate at the pharmacy counter: ‘Is this patient truly in recovery, or is this patient seeking this product so that they can sell it or trade it or whatever for illicit drugs?’ And that’s tough for pharmacists to make that determination.”

Some won’t dispense the treatments, he said, while others say, “‘Hey, I want to make sure, just like Naloxone (Narcan), that we see this as a vehicle to help people. Some will use it, some will misuse it, some will divert it.’”

Meanwhile, he said, the pharmacist association is focused on making sure pharmacies are “good access points” for treatments because, especially in rural areas, people may be able to access a pharmacy more easily than a doctor’s office.

“If your prescriber, physician, nurse practitioner is 45 minutes an hour away, what we’re trying to do is break down those barriers,” Mudd said. “These products are not available at every drugstore in Kentucky. They’re not stocked at Walgreens. They’re not stocked at your local independent pharmacy. But we know those are good access points.”