Study indicates risk of fatal birth defects is higher in counties with mountaintop-removal coal mining

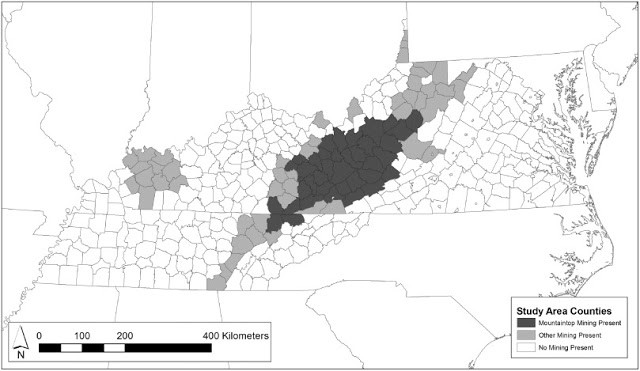

“Children born in counties home to mountaintop coal mines had a 26 percent higher risk of suffering” a fatal birth defect “compared to ones born in non-mining regions,” according to a new study, Dan Vergano of USA Today reports. The study, led by health economist Melissa Ahern of Washington State University in Spokane, will appear in the upcoming Environmental Research Journal. (Map shows counties with coal mines in 1996-2003, with “mountaintop” mining counties in darker gray)

Air and water pollution from mountaintop mining led Ahern and her colleagues “to look for health effects on infants” in West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, Vergano writes. The researchers found birth defects in mountaintop mining areas were elevated above non-mining areas in six of seven categories, including heart, lung and gastrointestinal. Because of an already established connection between poverty and birth defects, the researchers then “controlled for social factors such as smoking, drinking, mother’s education, race and other poverty-related factors” and found a 26 percent increased risk of fatal birth defects in mountaintop-mining counties, Vergano reports.

Air and water pollution from mountaintop mining led Ahern and her colleagues “to look for health effects on infants” in West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, Vergano writes. The researchers found birth defects in mountaintop mining areas were elevated above non-mining areas in six of seven categories, including heart, lung and gastrointestinal. Because of an already established connection between poverty and birth defects, the researchers then “controlled for social factors such as smoking, drinking, mother’s education, race and other poverty-related factors” and found a 26 percent increased risk of fatal birth defects in mountaintop-mining counties, Vergano reports.

Air and water pollution from mountaintop mining led Ahern and her colleagues “to look for health effects on infants” in West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, Vergano writes. The researchers found birth defects in mountaintop mining areas were elevated above non-mining areas in six of seven categories, including heart, lung and gastrointestinal. Because of an already established connection between poverty and birth defects, the researchers then “controlled for social factors such as smoking, drinking, mother’s education, race and other poverty-related factors” and found a 26 percent increased risk of fatal birth defects in mountaintop-mining counties, Vergano reports.

Air and water pollution from mountaintop mining led Ahern and her colleagues “to look for health effects on infants” in West Virginia, Kentucky, Tennessee, and Virginia, Vergano writes. The researchers found birth defects in mountaintop mining areas were elevated above non-mining areas in six of seven categories, including heart, lung and gastrointestinal. Because of an already established connection between poverty and birth defects, the researchers then “controlled for social factors such as smoking, drinking, mother’s education, race and other poverty-related factors” and found a 26 percent increased risk of fatal birth defects in mountaintop-mining counties, Vergano reports.

A spokesman for the National Mining Association “suggested adding more demographic factors to the study might remove the elevated birth defects,” Vergano writes, then quotes environmental and pediatric-health expert Lynn Goldman of George Washington University as saying “It isn’t proof of cause and effect” and paraphrases her: “Because the study is the first of its kind, public health researchers will need to reproduce the study results to feel confident it has uncovered a real link, she cautions. Further studies will be needed to show how exposures in mountaintop mining communities could lead to more birth defects.” (Read more)