By Tara Kaprowy

Kentucky Health News

After hearing experts say communities should take the lead in improving the quality of health care and lowering its cost — especially because there are so many unknowns about the new federal health care law — McCreary County mother and health activist Susan Taylor stepped up to the microphone Tuesday in Somerset.

“I hear what you’re saying, but how do you go about getting our leaders motivated?” she asked a panel at the 2011 Howard L. Bost Memorial Health Policy Forum.

“That has sort of been my challenge,” replied William Hazel, health and human resources secretary in Virginia. “It’s an education process.”

There were no simple answers, but experts, medical professionals and community members were willing to ask the tough questions and offer their views at the forum, sponsored by the

Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky and named for a Kentuckian who played a major role in writing the Medicare law.

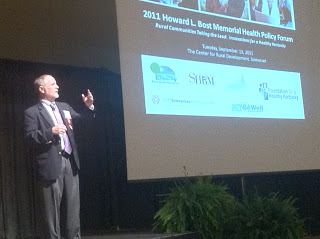

Again and again, experts said solutions can be found by going local, rather than focusing on goings-on in Washington or Frankfort. “My whole point is this: Make it work where you live and work and the whole country will want to be like that,” said Len Nichols, left, professor of health policy and director of the Center for Health Policy Research and Ethics at George Mason University.

Nichols, the forum’s keynoter, advised state legislators and rural Americans to stay calm about health care, focus on what can be measured and change accordingly. “Forget politics,” he said. “Forget Obama. Don’t watch TV at all. Focus on where you live.”

He acknowledged that is easier said than done, because politicians can’t talk about health reform “without making half the population mad and half the population scared.” “People are scared, and why wouldn’t they be scared?” he asked. “It looked and felt and still feels like the Great Depression.”

But federal health reform is necessary, Nichols said, because the current system is unsustainable: 7 percent of the average family’s income went toward paying health insurance premiums in 1987. By 2006, it had risen to 17 percent and by 2016, withough reform, it is projected to be 34 to 45 percent. Medicare is likewise unsustainable, Nichols said, with a projected 7.3 percent of the gross domestic product being spent on paying for Medicare alone by 2035.

While the majority of the new health law won’t be implemented until 2014, and with repeal still a possibility if Obama loses the 2012 presidential election, community-based changes can contain health care costs.

In West Tennessee, businesses have banded together and formed the Memphis Business Group on Health, which represents 350,000 employers, employees and their families. The group chooses its providers based on value and performance and, because its numbers are significant, providers are willing to comply with the group’s requirements. CEO Cristie Upshaw Travis said the private sector can “transform the market” by banding together in this way. “They’ve had absolutely no choice but to change how they do their benefits,” she said.

Hospitals, physicians and health plans are all assessed using survey reporting instruments, whether that means an administrator answering questions about the number of pressure ulcers in a hospital or an insurance agent evaluating a plan on consumer engagement or chronic disease management. “Having this public report in our community has had an impact on the improvement, quality and efficiency of care,” Travis said. “In one way, it gave them something to focus on.”

In North Carolina, the state has turned to patient-centered medical homes for Medicaid patients. In this model, a family doctor’s office becomes the hub of a patient’s care. With the help of physician assistants and nurse practitioners, doctors use electronic health records to track patients between visits, communicate with specialists, monitor blood sugar and blood pressure and are actively involved in whether patients are getting enough exercise or taking their medicine.

There are 1,400 medical homes in North Carolina, the first of which was developed in a rural county in the late 1980s. “There was a huge access problem, the emergency room was overrun,” said Tork Wade, executive director of

Community Care of North Carolina. But by increasing access points, linking patients with a primary care physician and engaging community leaders — “That was another key thing,” Wade said — the effort worked. “We got money to go to another 12 counties,” Wade said. “(The model) responded to a real need, it wasn’t just top down.”

The state’s embrace of Wade’s non-profit program, which is effectively a managed-care plan for Medicaid, struck a contrast with Kentucky’s current shift to a managed-care system run by competing, for-profit companies. “My problem with a competing system is that it doesn’t lift all boats,” Wade said at a breakout session, where advocates said the Kentucky plan seems more concerned with saving money than ensuring quality.

Kentucky Health and Human Services Secretary Janie Miller, left, a McCreary County native who gave openign remarks, said Medicaid should provide what patients need, “but there hasn’t really been a strong, deliberate, structured method . . . to really assure we’re getting the best bang for the buck.”

Though the North Carolina program is now statewide, the key was that the answers came from the communities, Wade said: “It has to be local. If it doesn’t work in the community, it’s not going to work. So you might as well start there.” Getting buy-in from rural communities was easier than in urban centers because “in urban areas there are competing health systems,” Wade said. “In rural areas, there is a single system of care and a history of people working together.”

Susan Taylor is going the local route by focusing on prevention with

Get Healthy McCreary County, which the health department there formed in 2007. The mission is to create awareness about healthy living in the community and promote any events that relate to it.

Though the group has hosted a few events, including a cooking class for kids and an educational session on the health reform law, Taylor says she is having trouble generating interest. “I just think they haven’t really realized how important our health is,” she said. “Once we get sick, then we’ll go to the doctor and worry about it. They don’t understand prevention.”

Taylor went to Tuesday’s forum to find answers, but came away with more questions. As for the federal health care law fixing community problems, Taylor — whose personal interest even prompted her to get a copy of the 1,200-page health care law from her congressman — admitted she doesn’t know if that will happen. “I think we saw that” at the forum, she said. “Even amongst the people who seem aware, still no one really know how it’s going to play out.”