Meant to be a conversation starter to fuel change for better health, the third-annual

County Health Rankings were released today, a health-evaluation tool that assesses the country’s counties on everything from their smoking to early mortality rates. Kentucky’s rankings did not change significantly from last year, with Oldham and Boone counties at the top and Owsley, Magoffin and Wolfe counties at the bottom of the list.

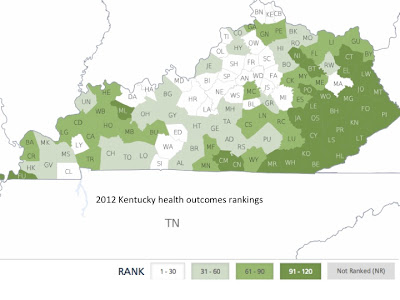

Kentuckians who are the least healthy live in the Appalachian swath of the state, the rankings show. Fulton County in Kentucky’s southwestern tip ranks low, though is not surrounded by other low-ranked areas. Counties that hug urban centers — Louisville, Lexington and Cincinnati — have the highest rankings. The data are compiled by the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute in collaboration with the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation.

Kentucky’s breakdown is not unusual, but part of a nationwide pattern in which the least healthy counties are often in rural, sparsely populated areas, said Dr. Patrick Remington, lead researcher and associate dean for public health at UW’s

School of Medicine and Public Health. “At the other end, you see urban centers as having similar problems and often ranking at the bottom of the list,” he said. “Another pattern is some of the suburban communities, ring communities, are some of the healthiest communities.”

Counties are ranked in two ways: health outcomes (such as premature death rates, low birthweight, how good or bad people feel physically and mentally) and health factors (such as smoking, obesity and binge-drinking rates). In health outcomes, graphic above, Oldham, Boone and Calloway ranked first, second and third respectively. Owsley County was ranked last, preceded by Martin and Wolfe counties.

In health factors, left, Woodford County ranked first, followed by Oldham and Boone. Clay County (labeled CY) was in last place, preceded by Magoffin and Wolfe counties (MG and WO).

Though Kentucky’s counties are ranked from 1 to 120, because of the small sample sizes in many of them, the rankings do not “represent statistically significant differences from county to county,” the rankings website reads. Sources for the data also change, so direct comparisons from year to year are also inexact, Remington said. This year, researchers tracked the number of fast-food restaurants in a county and levels of physical inactivity. They also used premature death rate trends over 10 years, a hard number that alone can indicate progress, Remington said.

Though Remington said he would “be naive to say the competitive element doesn’t pique interest in the rankings,” they are “not really intended to be a race to the top.” Instead, rankings should be used as a “Polaroid snapshot of community health,” Remington said. The data should be used by officials to pinpoint problem areas, drill down and make policy changes in turn, he said.

That’s what Chip Johnson, mayor of Hernando, Miss., did. Participating in a teleconference about the rankings, Johnson talked about how policies aimed at improving health have changed his city. Officials have required sidewalks in all new and re-developments, he said. All new streets should be biking and pedestrian accessible. The city has partnered with schools so people can use their gyms to work out. And Johnson encouraged a local bank to donate land for a 37-acre park. “Banks are sitting on land they’ve repossessed and don’t know what to do with it,” he said. “We’re naming the park after the bank.”

The goal is to create infrastructure that will make it easier for people to make healthy decisions, he said, pointing out, “You can’t exercise your personal responsible for good health if your city or county does not give you that atmosphere or opportunity.” Johnson said he responded to this reality by strategically placing the city’s only farmers’ market, community garden and community center in its lowest-income area.

As indicated by the data assessed and Johnson’s efforts, “Much of what influences our health happens outside of the doctor’s office,” foundation President Risa Lavizzo-Mourey said, and factors like education rates, income levels and access to healthy food all play a part, researchers found. Data also show where someone lives can influence health. Excessive drinking, for example, is highest in Northern states. Rates of teen births, sexually transmitted infections and children living in poverty are highest in Southern states.

The rankings are based on several sources of data, from vital statistics to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention‘s Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, the world’s largest, on-going telephone health survey. “We found even though the data are available nationally, it requires a lot of time and effort,” Remington said. “This is one-stop shopping, not just for death and disease rates but for all of the factors that lead to a healthy community. Combining them allows people to start the conversation pretty easily.”

Susan Zepeda, CEO of the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky, applauded the effort. “Local health data can spur communities to action to create better health outcomes for all Kentuckians,” she said.

By Tara Kaprowy

By Tara Kaprowy