Panel of physicians at national conference discuss future of rural primary care, how to solve doctor shortages

More needs to be done to address the shortage of primary-care physicians, a big problem in rural areas and much of Kentucky, according to a panel of physicians at “Rural Health Journalism 2014,” Kris Hickman writes for the Association of Health Care Journalists, which sponsored the conference.

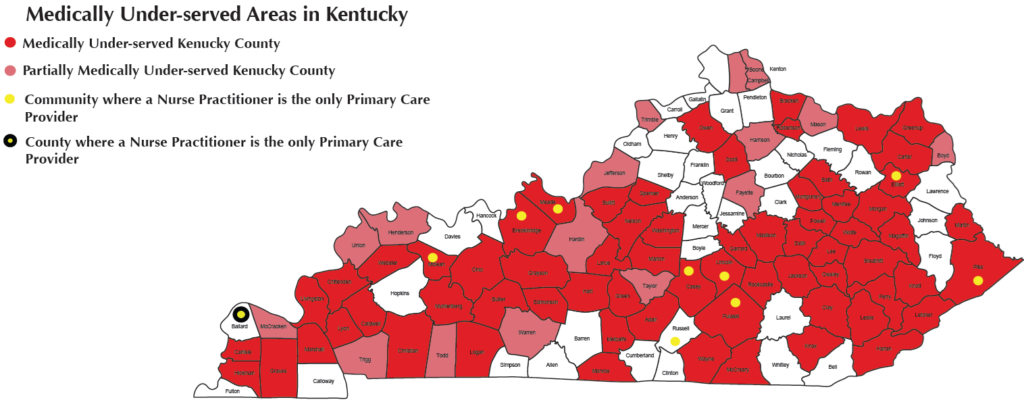

Almost half of rural U.S. counties, 44 percent, struggle with primary care physician shortages, said Andrew Bazemore, M.D., M.P.H., director of the Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care of the American Academy of Family Physicians. According to a presentation at the 2013 Kentucky Rural Medical Educators Conference, Kentucky had a 1,287:1 primary care physician to citizen ratio, which is 557 short of the national average.

The national shortage is expected to worsen soon because almost 27 percent of those providers are older than 60, said Mark A. Richardson, M.D., dean of Oregon Health and Science‘s School of Medicine.

Bazemore said the medical community needs to draw more attention to the need for more primary care physicians in rural areas. He also said that for every dollar spent on health care, only six or seven cents are spent on primary care. “States facing a shortage should remember that primary care is the logical basis of any health care system,” Bazemore said.

Richardson recommended that medical schools try to recruit students who have rural backgrounds because they’re more likely to return to practice in rural areas. He and Bazemore agree that students who practice in rural areas should be given loan forgiveness or scholarships. “Debt prevents many people from choosing primary care,” Bazemore said.

Richardson said the most important factor for where medical students end up practicing is where they completed their training. “Rural training is one of the highest predictors of a rural practice and should be required,” he said. To do this, the government-imposed cap on graduate medical education spending would have to be abolished.

“Medical care is not a free market dynamic,” Richardson said. “We pay for health care transactions, rather than health.” (Read more)