Leaders in health care and education meet on child obesity and what can be done about it, and not just in the schools

By Al Cross

Kentucky Health News

Children who are physically active are likely to be better learners, but not enough Kentucky schools seem to put that knowledge into practice, speakers suggested at last week’s Kentucky Summit on Childhood Obesity and Physical Activity at the University of Kentucky.

Kentucky ranks eighth in child obesity, and nationally, adult obesity is expected to grow from 30 percent of the population now to 60 percent by 2030.

“Many of the adults who will be obese in 2030 are the children in Kentucky schools today,” said Dr. Mary Lynne Capilouto, the wife of UK President Eli Caiplouto. The couple hosted an opening brunch for the conference, and at one small-group session.

The conference was an unusual gathering of people from education and health care, who don’t discuss common interests enough, said Terry Brooks, executive director of Kentucky Youth Advocates, which staffed the conference. “Our intent is to put together a guiding coalition . . . and make something happen in 2015-16.”

That would probably include legislation, but “We can’t legislate ourselves out of this problem,” educator Leon Mooneyhan told the group. “We need to change the mindset of our society,” with multifaceted solutions. Mooneyhan, a former superintendent in Shelby County, is CEO of the Ohio Valley Educational Cooperative, which assists school districts.

He said each district needs a strong “wellness committee” to focus on health, nutrition and physical activity and promote such measures as integrating physical activity into the classroom and not using denial of recess as punishment for misbehavior. “We really need to focus at the elementary schools,” he said. “That’s where it starts.”

The biggest obstacle may be the educational system itself.

|

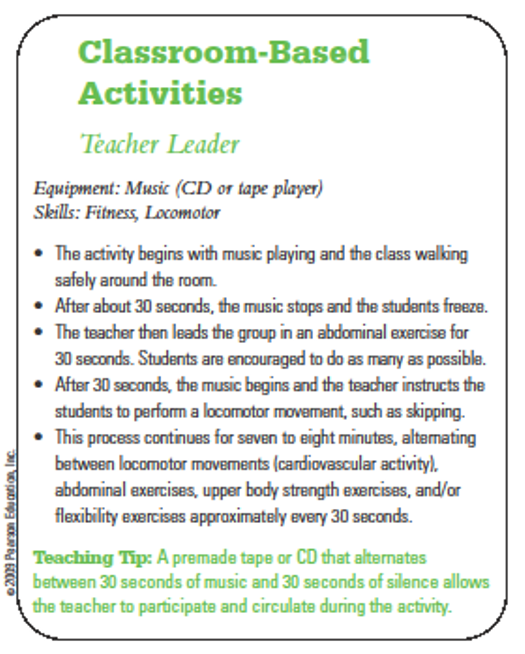

| An example of classroom-based physical activity, from Dr. Heather Erwin’s PowerPoint presentation |

Some schools are reluctant to carve out time for physical activity because of pressure to spend time preparing students for annual achievement tests, but research shows that more physical-activity time “does not appear to to adversely impact academic performance,” said Heather Erwin, Ph.D., a UK specialist in kinesiology, the study of human movement.

Erwin said some schools have started intensive math instruction lasting 90 minutes, and students could benefit from two of three physical-activity breaks in such a long classroom session. She said, “So many teachers will say after implementing physical activity, why haven’t we been doing this all along?”

“If your butt is numb, your brain is, too,” said Jamie Sparks, director of the School Health and Physical Education Network for the state Department of Education.

Sparks said it’s unfortunate that some schools are using recess as extra study time before achievement tests. Stu Silberman, executive director of the Prichard Committee for Academic Excellence, said research has shown that students do better on achievement tests on days that they have physical activity.

“There is an achievement gap related to obesity,” but many teachers don’t see the connection, Silberman said. When students take part practical, in-class programs like those Erwin mentioned, “it becomes a habit for the rest of their lives. . . . Frankfort’s not the answer on this.

Tom Shelton, who succeeded Silberman as superintendent in Fayette County, said asking teachers “to do one more thing is almost criminal,” they are so busy, but nations such as India and China emphasize physical activity, and “It’s amazing to me that we’re going the other way. . . . We know for a fact that healthy students are better learners.”

Shelton said “Poverty is the number-one barrier to student achievement,” and part of that is “lack of good food options.”

The face of poverty has changed to one of obesity, said David Jones Jr., a member of the Jefferson County school board and a Louisville venture capitalist. Poor people often eat poor food and don’t get enough exercise. “The problem is, we don’t know how to eat. We don’t know how to deal with calorie-rich environments,” Jones said.

Jones was among those who said the solution to child obesity lies in the community at large, not just in its schools.

“It has to be parents and schools and the community and legislators,” said Susan Zepeda, president of the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky, which funded the conference. “This challenge is about nutrition policies, physical-activity policies and building our environment with health in mind.”