Appalachian women are more likely to get cervical cancer and die from it, but pass up vaccine partly because of fatalistic beliefs

Kentucky Health News

A fatalistic belief that getting or preventing cancer is beyond a person’s control is one of many reasons young women in Appalachian Kentucky are likely to not get or complete the series of HPV vaccinations to prevent cervical cancer, according to a study by researchers at the University of Kentucky, published in The Journal of Rural Health.

“Our study found that fatalistic beliefs influenced immunization behaviors, which is concerning, given the high success rates of preventing HPV infection and cervical cancer through HPV vaccination and the elevated burden of cervical cancer in Appalachian Kentucky,” Robin Vanderpool, lead author of the study, said in an email.

The human papillomavirus, or HPV, is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the U.S., affecting an estimated 79 million individuals. Two types of HPV cause two-thirds of all cervical cancers, and unlike any other cancer, there is a three-dose HPV vaccine that can prevent it, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The UK researchers found that the women in the study who believed they had limited control over their health generally and limited control over cervical cancer specifically were significantly less likely to complete the HPV vaccine series than those who did not have this belief.

“This is an important finding because rural Appalachian residents often perceive cancer as pervasive, inevitable and mostly hereditary,” the authors wrote.

The 344 rural Appalachian women who volunteered for the study were given the first dose of vaccine free of charge, and surveyed about their beliefs regarding cancer. They were followed for nine months after the first dose to determine completion rates.

Other studies had determined that many Appalachian women don’t get or complete the HPV vaccine because of cost, lack of transportation, cultural views, lack of knowledge about cervical-cancer prevention and limited support from parents, peers and health-care providers. A belief in fatalism can now be added to this list.

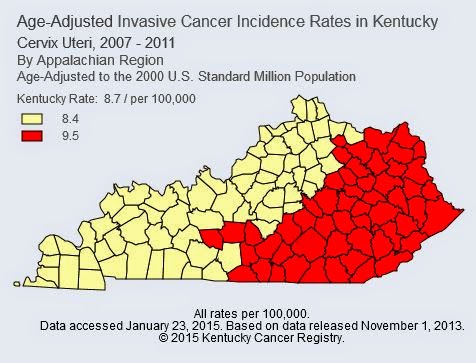

Health advocates are working to get through these barriers because Appalachian Kentucky has the state’s highest rates for cervical cancer and deaths from it, according to the Kentucky Cancer Registry. This, in a state that is among the top 14 for the most cases of HPV-related cervical cancers in the nation, according to the CDC.

Health advocates are working to get through these barriers because Appalachian Kentucky has the state’s highest rates for cervical cancer and deaths from it, according to the Kentucky Cancer Registry. This, in a state that is among the top 14 for the most cases of HPV-related cervical cancers in the nation, according to the CDC.

Kentucky has a low HPV vaccination rate, with only one in four adolescent women initiating the vaccine and less than one in nine receiving the full series, according to The Kentucky Cancer Consortium. These rates are even lower in Appalachia, says the study.

Kentucky has a low HPV vaccination rate, with only one in four adolescent women initiating the vaccine and less than one in nine receiving the full series, according to The Kentucky Cancer Consortium. These rates are even lower in Appalachia, says the study.

The CDC recommends routine HPV vaccination for females ages 11-12 and catch-up vaccination for females ages 13-26. The second dose should be given one to two months after the first injection; the third dose should be administered six months after the first dose. Males are also encouraged to get the vaccine.

The study acknowledged that future such studies should compare women who have received the first dose of the vaccine, as in this study, against women who had not. It also suggests that these findings indicate a need for future research in how to educate and intervene with Appalachian women in a way that is culturally sensitive to improve HPV vaccination rates and to impact cancer disparities that affect the women in the region.