Proposed Medicare premium hike could cost Kentucky a lot, because some on Medicare are also on Medicaid

UPDATE, Oct. 28: the budget deal agreed to by the president and Congress eliminates the Medicare premium increase.

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

If a proposed increase in Medicare premiums is approved later this month, Kentucky will have to find a way to cover as much as an extra $100 million a year for Medicare beneficiaries whose premiums are paid by the federal-state Medicaid program.

“The state is concerned about the budget implications surrounding this issue,” the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services said in a statement. “Since Medicaid is funded in great part with federal dollars, the Department for Medicaid Services must comply with all federal mandates. . . . All states are following this issue closely, since the decision by the (U.S. Department of) Health and Human Services to increase Medicare Part B premiums could have significant budget implications for state Medicaid agencies.”

HHS has not yet finalized its projections, but is expected to announce the final 2016 Medicare monthly premiums later this month.

Premium increases could affect about 15 million of the 51

million people enrolled in Medicare Part B, which covers doctors’

services, outpatient hospital services, some home-health care and other

items. Those who are in both programs are expected to have an increased

premium of $55 a month.

If the $55 hike goes through, “Kentucky taxpayers will be hit

with another $100 million a year Medicaid bill in 2016,” writes David

Adams, a strong critic of the federal health-reform law who sued unsuccessfully to stop Gov. Steve Beshear’s embrace of the law.

On his Kentucky Progress blog, Adams said some 200,000 Kentucky Medicare recipients are also on

Medicaid. The Cabinet for Health and Family Services did not immediately

respond to a request to confirm that number.

“This is a huge issue for states,” Matt D. Salo, executive

director of the National Association of Medicaid directors, told The New

York Times. “To finance Medicare, the federal government would shift

billions of dollars in costs to state Medicaid programs.”

It’s also an issue for the federal government, which pays most Medicaid costs. Congress and the Obama administration are looking for ways to stop these Medicare premium hikes, including using administrative action, noting that premiums “could rise by roughly 50 percent for some beneficiaries next year,” Robert Pear reports for the Times.

But Pear also reports that Republicans, who are looking at “the cost of avoiding such big premium increases, $77.5 billion by some estimates,” may see this as a problem, with aides to Speaker John Boehner telling the Democratic leadership that the “cost would have to be offset by savings elsewhere in the federal budget.”

Why are some people in both programs? “Medicare enrollees who have limited income and resources may get help

paying for their premiums and out-of-pocket medical expenses from

Medicaid,” the National Conference of State Legislatures explains. “Often referred to as ‘dual eligibles,’ these individuals are among the

disabled, most chronically ill, and costly in either program. It’s been

estimated that on average the dual eligible population costs 60 percent

more than non-dual eligible individuals. Medicare covers their acute and

post-acute care services, while Medicaid covers Medicare premiums and

cost sharing, and—for those below certain income and asset

thresholds—long-term care and social supportive services and, until

2006, prescription drugs, among other services. Approximately half

initially qualify for Medicare because of disability rather than age and

nearly one-fifth have three or more chronic conditions.”

Most on Medicare won’t pay more, so rest have to make it up

Gail Buckner of Fox Business explains why some Medicare recipients may see a 50 percent increase in their premiums, while most will not.

Medicare, the federal health insurance program for those 65 and older, is comprised of Medicare Part A, which covers hospital stays, and Part B, which covers doctor visits and out-patient services.

Part A is paid for by a 2.9 percent tax on employers and employees. The cost of Part B is shared by the federal government, which typically pays 75 percent, and premiums.

A “hold harmless” rule set by Congress years ago that says if a senior’s Part B premium goes up more than their Social Security benefit, their premium can remain the same.

Because inflation has been so low, many Social Security beneficiaries will not get a cost-of-living adjustment next year, which means their Medicare premiums won’t change. This year, 70 percent of retirees fall into this category,

But that also means that the remaining 30 percent will have to bear the entire increase in the premiums.

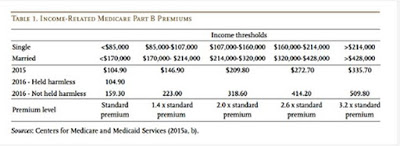

The New York Times reports that Medicare actuaries predict an increase of $159 a month for most standard premiums as well as an increase in the annual deductibles, estimating a rise to $233 next year, from $147 in 2015.

Those who will have to pay the higher premiums are: dual eligibles; new retirees; individuals who are enrolled in Medicare, but do not receive Social Security, such as retired teachers; and wealthy retirees, who make up 6 percent of seniors.