Appalachian smoking cessation studies suggest changes in tactics, such as being blunter with pregnant smokers

Beth Bailey, director of the Primary Care Research Department of Family Medicine at East Tennessee University, reported on her research in the fall newsletter of the Appalachian Translational Research Network.

The first project Bailey directed attempted to address the high rates of pregnancy smoking in the region and the consequent poor child health and development outcomes, writes Bailey, who is also a professor of medicine at ETSU’s James H. Quillen College of Medicine.

This project, implemented in obstetric practices, found that “rural Appalachian women prefer detailed information about the significant fetal harm and long-term developmental effects that can result from smoking during pregnancy” instead of the current approach of providing a positive message with specific tips and techniques to stop smoking.

“These findings led us to revise our intervention efforts, better tailoring them to the needs of Appalachian women, increasing success rates,” Bailey writes.

Kentucky leads the nation in smoking by pregnant mothers, with 22.5 percent of Kentucky women reporting that they smoked during pregnancy; and nearly one in every 10 Kentucky babies are born at low-birth-weight, to which smoking during pregnancy contributes, according to the the annual Kentucky Kids Count report.

|

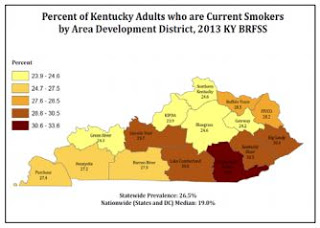

| Graph from Ky. State Innovation Model report |

The second project, also led by Bailey, examined the differences between those who successfully quit smoking following intervention by primary-care providers, and those who didn’t.

In Kentucky, 26.5 percent of adults smoke, but this rate is much higher in Eastern Kentucky with rates of 30.4 percent in the Big Sandy Area Development District, 30.5 percent in the Kentucky River Area Development District and 33.6 percent in the Cumberland Valley Area Development District , according to the Kentucky State Innovation Model Draft Population Health Improvement Plan.

This examination found that the presence of chronic health conditions related to smoking did not make a difference in whether a person quit smoking, and people with depression or other mental-health problems, or who were disabled and unable to work, were more than twice as likely to fail to quit smoking.

These findings have led to a modification of primary-care smoking intervention, to include a kook at mental health and work history, as well as advsing such patients to stay busy when trying to quit.

Bailey writes that she hopes these findings will help others in the region to “benefit from this knowledge and enhance smoking cessation efforts in other areas of Appalachia, where the burden from this health behavior is substantial.”