Trying to stop overdose epidemic, CDC tells docs to limit most opioid prescriptions to 3-7 days, use low doses and warn patients

|

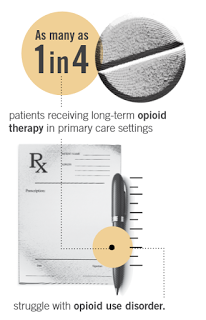

| Graphic from CDC guideline brochure |

Kentucky Health News

Doctors who prescribe highly addictive painkillers for chronic pain should stop and be much more careful to thwart “an epidemic of prescription opioid overdoses” that is “doctor-driven,” the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said Tuesday, March 15.

“This epidemic is devastating American lives, families, and communities,” the CDC said. “The amount of opioids prescribed and sold in the U.S. quadrupled since 1999, but the overall amount of pain reported by Americans hasn’t changed.”

Kentucky ranks very high in use of opioids and overdoses from them, and Louisville reported a big increase in overdoses this month, Insider Louisville reports.

The agency said doctors should limit the length of opioid prescriptions to three to seven days, use “the lowest possible effective dosage,” monitor patients closely, and clearly tell them the risks of addiction.

It said most long-term use of opioids should be limited to cancer, palliative and end-of-life treatment, and that most chronic pain could be treated with non-prescription medications, physical therapy, exercise and/or cognitive behavioral therapy.

The guidelines are not binding on doctors, but Dr. Thomas Frieden, the CDC director, “said state agencies, private insurers and other groups might look to the recommendations in setting their own rules,” the Los Angeles Times reported.

However, Modern Healthcare reported that the guidelines are unlikely to change physicians’ practices. “One current hurdle to curbing the number of prescriptions is that it’s much easier for a busy clinician to prescribe a 30-day supply of oxycodone or Percocet to treat a patient’s chronic pain than it is to convince him or her to do physical therapy,” Steven Ross Johnson writes. “The time constraints affecting physicians’ practice has never been more acutely felt than in this era of health-care reform that emphasizes quality and value-based payment.”

Money could be a key in making the guidelines effective. Sabrina Tavernise of The New York Times writes, “Some observers said doctors, fearing lawsuits, would reflexively follow them, and insurance companies could begin to us them to determine reimbursement.” The federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services could also play a role.

Johnson notes that physicians are trained to “reserve opioids for severe forms of pain . . . but in the 1990s, some specialists argued that doctors were under-treating common forms of pain that could benefit from opioids, such as backaches and joint pain. The message was amplified by multi-million-dollar promotional campaigns for new, long-acting drugs like OxyContin, which was promoted as less addictive.”

Purdue Pharma, maker of OxyContin, agreed to pay $600 million in penalties to settle federal charges that it over-promoted the drug to doctors, prompting the epidemic, especially in Central Appalachia.

“When reports of painkiller abuse surfaced, many in the medical field blamed recreational abusers. In recent years, however, the focus has shifted to the role of doctors,” Harriet Ryan and Soumya Karlamangla report for the Times, noting that a 2012 analysis “of 3,733 fatalities found that drugs prescribed by physicians to patients caused or contributed to nearly half the deaths.”

Doctors, insurers, drug companies and government agencies “all share some of the blame, and they all must be part of a solution that will probably cost everyone money,” Caitlin Owens writes for Morning Consult, which also notes prescribers’ complaints and CDC’s responses.