Study finds no link between tighter controls on prescription opioids and increased use of heroin; some researchers disagree

|

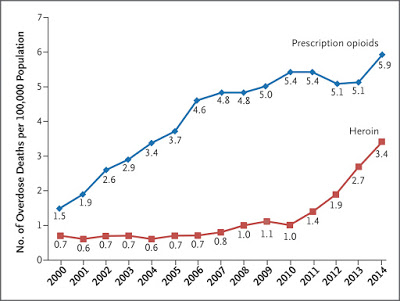

| National overdose-death rates for heroin (red) and prescription opioids (blue) |

By Al Cross

Kentucky Health News

Soon after Kentucky cracked down on “pill mills” where prescription painkillers were easily available, officials noticed a jump in heroin arrests and overdoses, and many presumed that one helped lead to the other. A study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found no link between the two, at least on a national scale, but some other experts disagree.

The study was conducted by physician William Compton of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, pharmacy Dr. Christopher Jones of the Department for Health and Human Services and public-health specialist Grant Baldwin of the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

They wrote, “It appears that the shift toward heroin use among some non-medical users of prescription opioids was occurring before the recent policy focus on prescription-opioid abuse took hold.” They note that heroin use began to increase by 2007, and that a pill-mill crackdown in Florida, similar to Kentucky’s, was followed by only a small increase in heroin overdoses.

“The results of these studies consistently suggest that the transition to heroin use was occurring before most of these policies were enacted, and such policies do not appear to have directly led to the overall increases in the rates of heroin use,” the researchers wrote. “Although the majority of current heroin users report having used prescription opioids non-medically before they initiated heroin use, heroin use among people who use prescription opioids for non-medical reasons is rare, and the transition to heroin use appears to occur at a low rate.”

They said the shift from prescription opioids to heroin is most prevalent among “persons with frequent non-medical use and those with prescription opioid abuse or dependence,” and is driven mainly by cheaper, purer and more accessible heroin.

Those conclusions drew a letter to the journal from researchers who have concluded otherwise. Theodore Cicero and Matthew Ellis of the Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis wrote, “A growing body of research has shown direct associations between the introduction of reformulated OxyContin and increases in rates of heroin use.” The reformulated drug was much harder to inject; the federal researchers looked at the possible effect of the change and discounted it.

The critics didn’t mention state crackdowns, but wrote, “It would be unwise for the agencies that the authors represent to ignore unanticipated negative aspects of efforts to limit supply, such as a shift to heroin in some persons, even if they represent a small part of the total heroin problem.”

The federal researchers concluded their report with lines few could disagree with: “Fundamentally, prescription opioids and heroin are each elements of a larger epidemic of opioid-related disorders and death. Viewing them from a unified perspective is essential to improving public health. The perniciousness of this epidemic requires a multi-pronged interventional approach that engages all sectors of society.”

“The last sentence is the most important,” said Van Ingram, director of the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy. “Prescribing regulations are more about slowing the creation of new people obtaining an opioid-use disorder. If we keep prescribing at the same rates this country has been this problem never gets solved.”