Nursing homes say Ky. has highest malpractice insurance costs and needs lawsuit review panels to keep providers and facilities

Kentucky Health News

The state’s nursing-home lobby is renewing its effort to get legislative insulation from lawsuits, a prospect that could improve if Republicans control the state House after Tuesday’s election.

Kentucky needs medical liability reform to stay competitive with its surrounding states, all of which have enacted some form of it, representatives of the Kentucky Association of Health Care Facilities told a legislative committee.

“It makes us not a friendly state to operate long-term care services,” Betsy Johnson, president of the association, said at the Nov. 2 meeting of the Interim Joint Committee on Health and Welfare, held during the association’s annual meeting in Louisville. “Providers are leaving Kentucky and new companies will not even consider locating in our commonwealth because of the high cost of health-care liability.”

Kentucky has at least one nursing home in every county, with a total of 281 nursing homes and 88 personal care homes. Combined, these facilities care for over 36,000 people, provide over 30,000 jobs and provide $200 million in state and local taxes, the group said.

|

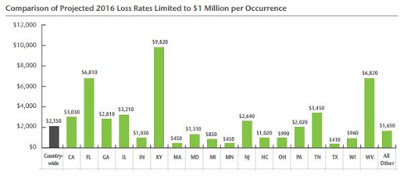

| Graphic Aon 2015 Long Term Care report |

Citing a recent study, Johnson said Kentucky’s long-term care providers are paying $9,350 per bed in liability insurance, the highest of any state. The study found Kentucky paid over $400,000 per claim in 2015, “the highest claims severity of all the states profiled in the Aon study,” Johnson said. Aon Risk Solutions is a risk-management and insurance company.

Kentucky also had the highest loss rate of Medicaid dollars in the study, which means that “14.66 percent of Medicaid reimbursement dollars that facilities receive end up going back out to cover losses,” Johnson said. “That is money that is not being used to provide care to the residents that we are committed to serving.”

Aon said in a statement, “Kentucky’s high cost of liability may be related to its lack of restrictions on tort actions. The state constitution prohibits limits on non-economic damages and there are no statutes concerning qualifications of expert witnesses, certificates of merit, pre-trial alternative dispute resolution or limits on attorney’s fees.”

For several years, nursing homes have been trying to get the legislature to require that medical-malpractice lawsuits be reviewed by a three-person panel to determine if a case has merit before the suit could proceed. Panel findings would be admissible in court, but not legally binding. The legislation has passed the Republican-led Senate, but has not been heard in the Democrat-led House.

Sen. Ralph Alvarado, R-Winchester, a physician, said after the meeting that he will likely introduce the bill again, pointing out that 43 other states have some sort of tort reform.

“The motivation for me to run for office to begin with was tort reform,” he said. “It is kind of what has gotten me here. So this is the big white whale that I am chasing and if I harpoon it and I get voted out of office, I can leave with a smile on my face. So, I am really hoping to get this accomplished.”

Another Senate bill, sponsored by Sen. Danny Carroll, R-Paducah, called the “truth in advertising” bill, would require advertisements of nursing-home inspection results to prominently include the date the deficiencies were found, the plan to correct them and whether they were corrected. It too passed the Senate, but was not heard in the House.

Such bills are opposed by the Kentucky Justice Association, formerly the Kentucky Academy of Trial Attorneys, a group comprised mainly of plaintiffs’ lawyers.

Maresa Fawns, CEO of the group, said in an email, “Restrictions on free speech that inform the public of negligence aren’t in the public’s interest. Neither is restricting the rights of individuals and businesses to seek redress in the courts. Both are protected by our constitution.

The heart of the matter is that less negligence through higher standards will result in fewer lawsuits. An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure and the solution is better staffing, better care, and less harm to our seniors.”

Medicaid approval delays

Johnson also said the association is working with the Cabinet for Health and Family Services and its Department of Community Based Services to get nursing-home patients approved for Medicaid more quickly. If a person hasn’t already qualified for Medicaid, they can’t apply for it until they have been admitted and because Medicaid will not pay for services until a resident has completed a 30-day stay, they will not process the application until the 31st day, she said in an e-mail. In addition, she added that it is “extremely difficult” to discharge a patient from a nursing home for “any reason, including non-payment” without an appropriate and safe discharge plan. The group said application approvals often take more than 90 days, with some taking more than a year.

As a result, nursing homes are caring for patients without being paid. This has amounted to an average balance of $170,093 per facility in September of 2016, according to a KAHCF survey for cases over 90 days. This problem is so bad that the survey found that a few facilities have stopped admitting Medicaid patients altogether and many more are considering it, Johnson said. The problem escalated in 2014 as a result of legislation that shifted the workflow to a centralized system, instead of the local DCBS offices, though that issue has recently been rectified, Johnson said.