Meth labs were more prevalent in ‘dry’ counties in 2004-2010; adds to evidence that making alcohol legal decreases drug use

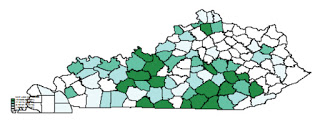

Meth use is more prevalent in counties where the sale of alcohol is illegal, say researchers at the University of Louisville. They looked at meth-lab seizures in Drug Enforcement Administration records and local-option ordinances in Kentucky counties from 2004 to 2010, and found that “the number of meth-lab seizures in Kentucky would decrease by 34.5 percent if all counties became wet.” (UofL maps: Meth lab seizures by county, with green indicating more busts; alcohol status: red for wet, orange for moist or limited, and yellow for dry)

In 2010 Kentucky had 39 “dry” counties (where all alcohol sales are banned), 32 “wet” counties (sales are allowed), 20 “moist” counties (contain some wet jurisdictions) and 29 “limited” counties (sale by the drink in restaurants meeting certain criteria). All the dry counties were rural; several have since gone wet or moist.

For the study period the mean lab-seizure rate was 2.17 per 100,000 residents in wet counties, 2.26 in moist counties and 3.92 in dry counties. The highest rates of lab seizures were along the border of Tennessee, a state in which beer is generally available but stronger drink is less so.

Christopher Ingraham of The Washington Post reports, “After running some statistical tests, the researchers found that this is more than just a simple correlation.” They said, “Our results add support to the idea that prohibiting the sale of alcohol flattens the punishment gradient, lowering the relative cost of participating in the market for illegal drugs.”

“In other words: people who buy alcohol in places where it’s illegal become accustomed to dealing with the black market,” Ingraham writes. “If you’re going to get punished whether you trade in booze or trade in meth, why not give meth a spin?” (Post graphic using data from UofL study)

The UofL research “fits in with other findings showing harmful effects of localized alcohol prohibitions,” Ingraham writes. “A 2005 paper in the Journal of Law and Economics found that when Texas counties changed from dry to wet, their incidences of drug-related mortality decreased by 14 percent as people substituted alcohol for other drugs. Records from the Kentucky State Police show that dry counties tend to have higher rates of DUI-related car crashes than wet ones, presumably because when you live in a dry county, you have to drive farther to get your booze. A 2010 report from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation found that binge drinking rates were often higher in Alabama’s dry counties than its wet ones.”