Federal judge says he will rule in Medicaid lawsuit by June 30; changes are set to start rolling out, county by county, on July 1

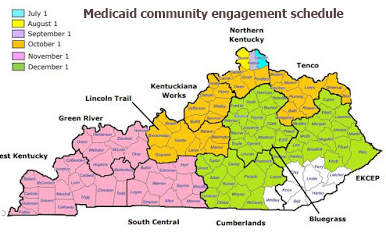

After hearing oral arguments Friday, a federal judge in Washington, D.C., said he will rule by June 30 whether federal law allows states to require people in Medicaid to work or take schooling — the most controversial part of a Kentucky Medicaid revamp that is scheduled to begin in Campbell County July 1 and be underway in all but eight counties by December.

U.S. District Judge James Boasberg noted the July 1 date after listening to lawyers for the state, the federal government and 16 Kentucky Medicaid beneficiaries who sued the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, claiming that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services waiver allowing Kentucky’s changes is illegal.

The plaintiffs said the plan’s work and reporting requirements would be “onerous” and “would end up limiting access to health insurance, the prime objective of Medicaid,” Lesley Clark reports for the Lexington Herald-Leader. Ian Gershengorn, an attorney with the National Health Law Program, told Boasberg that “The obvious intent is to undermine Medicaid.”

“Government lawyers argued that states would be more likely to embrace Medicaid expansion if they could impose similar restrictions,” Clark reports. Boasberg “could put all these expansion programs on the chopping block,” Deputy Assistant Attorney General Ethan Davis, representing HHS, told him.

Kentucky was the first state to get a waiver for a work-or-education requirement. “The outcome of the case could affect the fate of similar Medicaid work requirements approved by the CMS in Arkansas, Indiana and New Hampshire,” Dickson reports. “Arizona, Maine, Mississippi, Michigan, Utah and Wisconsin are seeking similar waivers.” Virginia is expected to join the group, following legislative enactment that wouldn’t have passed without agreement on a work requirement.

Opponents of the changes “said they don’t believe HHS’s argument,” Nathaniel Weixel reports for The Hill, a Washington publication. Boasberg, an appointee of Barack Obama, “appeared skeptical of the arguments used by the defendants, and his questions largely ignored them.”

Boasberg pressed Davis to explain how “community engagement” requirements such as work or schooling help with health care, “adding that promoting health and medical assistance are ‘two different things’,” Clark reports. “Davis said the program includes a boost for addiction treatment and noted that ‘a variety of studies’ have shown a relationship between health and community involvement.”

“The goal here is not to have benefits cut,” Davis said, adding that saving money wasn’t a goal of the waiver, but “a happy side effect.” The state has estimated that in the next five years, estimated Medicaid spending of $37.2 billion would be reduced to $35 billion, because the program would have 95,000 fewer members with the waiver than without it — partly from members’ failure to meet new requirements. (Tens of thousands of Kentuckians go on and off Medicaid each month.)

Initially, Bevin said the plan was the only way the state could afford to continue expansion of Medicaid to people with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, implemented by his Democratic predecessor, Steve Beshear, in 2014. “More recently, however, Bevin has told reporters that he doesn’t know ‘nor do I really care’ what the cost savings would be,” Clark notes. “The more important goal is helping dependent people to become healthy and productive, he said.”

Nevertheless, Bevin’s deputy general counsel, Matthew Kuhn, told Boasberg that the plan would keep the state from spending money it “does not have,” and “this is the only way we could afford to have expanded Medicaid.”

Bevin has said that without work requirements, he would eliminate the expansion, which at last count covered 493,000 Kentuckians. A county-by-county spreadsheet of enrollment in Medicaid, as of January 2018, is here.

“Gershengorn argued that Medicaid, unlike some other forms of public assistance, is not a job-training program, and the Trump administration lacks the authority to transform it into one,” Clark reports.

Gershengorn argued that the waiver “did not support the Medicaid Act’s purpose of furnishing medical assistance,” Virgil Dickson reports for Modern Healthcare. Gershengorn said, “Unlike some other public assistance programs, Medicaid is not a jobs-training program, and the administration does not have the authority to turn it into one. The rule of law requires that the president adhere to and uphold federal law, not subvert it.”

Weixel writes, “The work requirements get the most attention, but Kentucky’s waiver was notable for other reasons. It was the first state to charge premiums up to 4 percent of a person’s income. The current limit has been 2 percent. Kentucky was also the first state to lock people out of coverage for up to six months for failure to timely renew their coverage or to alert the state if their income or family circumstances have changed. Beneficiaries can also be locked out if their income is at least 100 percent of the poverty level and they fail to pay premiums. The Trump administration lawyers argued the lockouts are much more flexible than some that were approved under the Obama administration.”

The American Medical Association said Thursday that it opposes lockouts. “Discontinuing health care for thousands of our most vulnerable citizens for failure to meet administrative burdens is a cruel, bureaucratic response to our neediest patients,” AMA board member William McDade said in a press release. “As physicians, we recognize that many of our Medicaid patients lead complicated, difficult lives, and we should value empathy over rigid adherence to red tape.”