Perseverance is often needed to set up syringe exchanges, since local politicians have the say-so, and it’s a local election year

The new mobile exchanges will be run by the Northern Kentucky Health Department at locations of St. Elizabeth Healthcare. The Newport location will begin July 24 and the Covington location will start July 26, reports The River City News.

It took perseverance for the counties to establish the exchanges, overcoming social and political obstacles, like many other Kentucky counties that are still trying to create their own exchanges.

Campbell County approved an exchange in 2016, but state law requires approval from the city in which the exchange will operate, as well as the board of health and the county government, and Newport did not approve the exchange until February of this year.

Newport’s decision came after a cluster of HIV cases were identified in the region, as well as a high number of hepatitis C cases. From Jan. 1, 2017, to March 16 of this year, the NKHD had diagnosed 45 cases of HIV, 21 of them intravenous drug users. From 2009 to 2016, zero to five such cases were reported each year, department spokeswoman Emily Gresham-Wherle toldTerry DeMio of the Cincinnati Enquirer. The region also has a high rate of hepatitis C infections, typically carried by sharing of needles.

Kenton County and Covington had also approved a syringe exchange in 2016, but with a requirement that it could not start until two other Northern Kentucky counties in the NKHD district had operational exchanges. Campbell County’s exchange allows the Kenton County program to go forward; NKHD has operated one in Grant County for three years.

The new mobile units will provide clean needles, Naloxone overdose-reversal kits, offer HIV tests, and provide referrals for other health services, including addiction treatment. What they won’t do is provide condoms — which are also known to fight infectious diseases and commonly distributed in these programs — because the mobile exchanges will be located on the grounds of Catholic hospitals, DeMio reports.

Nevertheless, it appears that health officials in the area are grateful to St. Elizabeth for providing a site for the exchanges. Hospital spokesman Guy Karrick told DeMio that while the hospital couldn’t countenance the distribution of contraceptives, it wanted to get the exchange going as quickly as possible. He added that the exchange might be better situated on health department property.

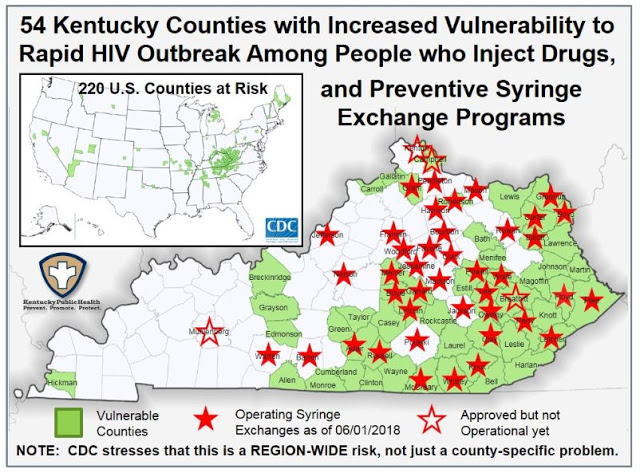

However, the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says 54 Kentucky counties are among 220 in the nation with the highest risk of an HIV or hepatitis C outbreak among IV drug users, and half of those 54 counties still haven’t approved exchanges.

One of the 27 high-risk holdouts, Clinton County, narrowly approved an exchange in March but backed out eight days later after complaints that it would encourage drug use. In the Republican primary election in May, the Fiscal Court magistrate most vocally opposed to the exchange defeated the county judge-executive, who favored it. The CDC says the county has the 11th greatest risk of any county in the nation for an HIV or hep-C outbreak among drug users.

Lawrence County, ranked 39th on the list, has also struggled with the issue. The county health board approved the proposal in September 2016, and the Louisa City Council followed suit in July 2017, the Fiscal Court unanimously rejected the proposal in March, WYMT-TV reported.

County Judge-Executive John Osborne told a packed house at the meeting that while he worries about HIV and hepatitis C, he worries about needles more, WYMT reported. “If you give out 40 needles at a time, you’re probably are going to see a lot more needles on the ground,” Osborne said. “It does bring a lot of people not from this area and that could cause a lot more problems.”

Public Health Director Debbie Miller told WYMT that she was disappointed but not surprised with the result. “I feel like the Fiscal Court is telling us that they’re not concerned with the fact that Lawrence County has been deemed one of the most vulnerable counties in the U.S. for an HIV or hepatitis C outbreak,” she said. “The bottom line is, no matter how uncomfortable these syringe exchange programs make us all feel, and they do all make us somewhat uncomfortable, they are proven to save lives.”

On the other hand, five Eastern Kentucky counties on the CDC list have started syringe exchanges in the last few months.

Perry, Letcher and Wolfe counties added exchanges in April “thanks to the expanded initiative by the Kentucky River District Heath Department,” Will Puckett reported for WYMT in April. That came a few months after after Lee and Owsley counties approved theirs.

Scott Lockard, the department’s public health director, told Puckett that the price of bringing in used needles and exchanging them for clean ones is small compared to the cost of treating diseases: $80,000 for a case of hepatitis C, “and the cost for someone who contracts HIV can cost over half a million dollars.”

Getting county officials to accept a syringe exchange program often depends on public education and perseverance, as evidence by another county that took two and one half years to get its exchange.

In March, Mary Meehan reported for Ohio Valley ReSource that it took Bourbon County two and a half years, and two failed votes, to get an exchange. It finally passed on a 6-2 Fiscal Court vote, and opened its doors in May.

Bourbon County is not on the CDC list, but the concerns there reflect those voiced across the state. People worry that the drug users will just take the needles and sell them; some say drug users are just looking for a handout; others say it is enabling their misbehavior, and others worry that it will draw addicts from surrounding counties that don’t have exchanges.

Research shows that syringe-exchange programs do not encourage the initiation of drug use, nor do they increase crime or the frequency of drug use among current users. They do reduce the spread of infectious diseases like HIV and hepatitis C; increase community safety; and connect people to treatment, according to the state Cabinet for Health and Family Services.

Meehan writes, “The health facts run up against deeply help opinions about the moral aspects of drug use and the notion that a needle exchange enables drug addicts to continue harmful behavior.” She reported that Bourbon County Judge-Executive Mike Williams encouraged other community leaders to persevere. “It took us three times,” he said. “Don’t give up, and keep presenting the facts.”

The State Journal in Frankfort recently said in an editorial that syringe exchanges are part of a holistic approach to fight the opioid epidemic, noting that the Franklin County’s exchange had provided more than 115,000 clean syringes to users, and collected more than 82,000 used ones.

The newspaper said there are still many in Franklin County who object to the exchange, but “We’d ask whether it’s better for a user to share needles and potentially infect others or be infected or to use clean needles and reduce or eliminate the chance of infection.”