Telling doctors about their patients who die of overdoses makes some reduce their prescribing of opioids

Telling doctors that their patients have died from drug overdoses reduce the physicans’ prescribing of opioids, the San Diego County medical examiner’s office in California found when it sent such letters to doctors.

The effect was modest, Carolyn Y. Johnson reports for The Washington Post: “Doctors who were informed of their patients’ deaths were 7 percent less likely to start new patients on opioids, and issued fewer high-dose prescriptions over the next three months, compared with those who did not receive a letter. In total, there was a 9.7 percent reduction in the total amount of opioids they prescribed,” according to results published in the journal Science.

The experiment was aimed at finding a solution to the opioid epidemic that is estimated to have killed almost 72,000 people from overdoses in 2017, 1,565 of them in Kentucky — a 10 percent increase nationally and an 11.5 percent increase in Kentucky from 2016. The synthetic opioid fentanyl was present in 68 percent of the deaths and in more than half of the Kentucky deaths.

The medical examiner’s letters, sent to hundreds of doctors who had prescribed opioids in the past year, also included recommendations for safer prescribing. Johnson described the letter as “supportive, but grim.” It read:

“This is a courtesy communication to inform you that your patient (Name, Date of Birth) died on (Date). Prescription drug overdose was either the primary cause of death or contributed to the death. … We hope that you will take this as an opportunity to join us in preventing future deaths from drug overdose.”

Johnson notes that the experiment addresses “the gulf between the care doctors provide and their knowledge about the consequences for patients,” noting that many doctors never know when their patients die from an overdose.

“Depending on what field you’re in, [the opioid epidemic] can feel a little remote. If you’re not a pain doctor or a primary-care doctor, it’s not quite as common to know or see your actions having a negative impact, which is what this is showing — it makes it very real,” Alexander Chiu, a surgeon at Yale New Haven Hospital who was not involved in the study, told Johnson. “As evidence-based as we are as a profession, sometimes anecdotes can be really powerful.”

The researchers write that prescribing may have declined among doctors because they thought they were being monitored, or because it allowed doctors to know what happens to their patients who don’t return for appointments, noting that they are disproportionately exposed to patients who return for their opioid prescriptions and are uneventful.

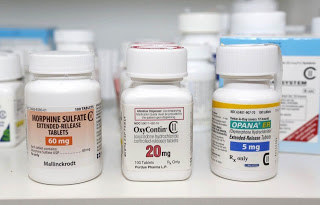

They also note that “people rely upon knowledge that is impactful, recent and easy to retrieve from memory when judging probabilities and making decisions.” For example, Johnson writes, “If a doctor learns that a few months after she prescribed 30 pills of OxyContin, a patient died of an overdose, the information may make her reconsider whether the prescription is truly necessary next time.”

The researchers urged other communities to adopt this strategy, noting that medical examiners’ offices already track overdose deaths and that all states (except Missouri) have a prescription drug monitoring programs. “It is thus feasible to “close the loop” on deaths by encouraging safe prescribing habits through the use of behavioral insights,” the report says.