County Health Rankings, released Tuesday, show a few big shifts

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

Some Kentucky counties that are actively working to improve their community health made significant gains in the latest County Health Rankings issued by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and the University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute.

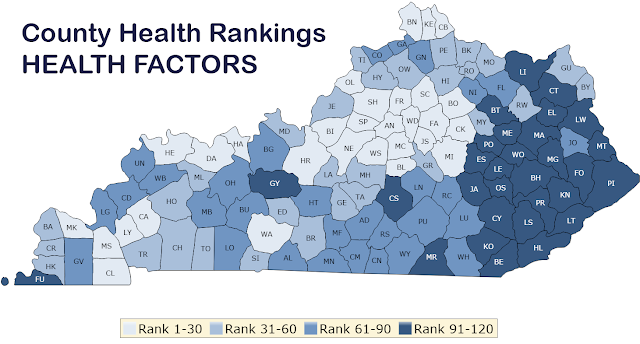

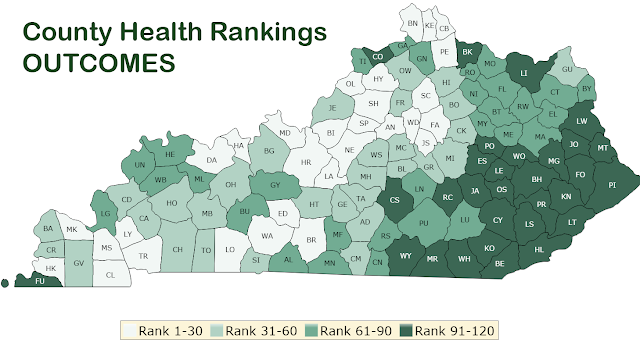

The rankings measure health outcomes, gauged by life expectancy and measures of quality of life; and health factors, such as access to physicians and areas to exercise, tobacco use, children living in poverty, violent crime, long commutes and other environmental factors.

Clinton County, in Appalachian Southern Kentucky, moved up 30 notches in health outcomes, to 64th from 94th among Kentucky’s 120 counties. Pendleton County, in Northern Kentucky, went up 31 slots, to 25th from 56th. Lyon County, in Western Kentucky, rose to eighth from 38th.

Clinton County has ranked in the bottom fourth of counties for health factors and outcomes for many years. It moved up only five slots, to 90th, for health factors, but its big gain in outcomes was significant.

The improvements could be an indication that the efforts of the Clinton County Healthy Hometown Coalition that was created in 2013 are beginning to pay off. The coalition, which was created with the help of a grant from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky, has largely focused on efforts to improve the health of the county’s children, such as building walking paths and playgrounds as well as working to increase physical activity and nutrition programs in the schools, which banned tobacco.

“The Clinton County coalition is a great example of community coming together to identify a significant local health issue and develop a comprehensive plan to make actual, measurable improvements,” said Ben Chandler, president and CEO of the foundation. “Members represent a broad cross-section of the community. That’s essential to developing and implementing programs that address the myriad factors that affect health.”

Most counties’ changes were insignificant; the rankings compare a state’s counties against each other without national comparisons, so when one moves up, another moves down.

In health outcomes, 19 counties moved up at least 10 notches since last year, and another 14 moved down by at least 10. In health factors, about 12 counties improved at least 10 notches and 11 dropped by at least 10.

Because the shifts in the rankings for most counties are so small that they are statistically insignificant, the researchers have placed counties in four groups of 30 counties, called “quartiles.” The rankings are meant to be viewed more as a general categorization of a county’s health status, rather making specific comparisons with counties that are relatively close in the rankings.

The bottom quartile for both health outcomes and factors continues to be almost entirely Appalachian. The only exceptions for health outcomes are Fulton County, in the Mississippi Delta at the state’s western tip, and Carroll County, between Louisville and Cincinnati. The exceptions for health factors are Fulton County and Grayson County, in west-central Kentucky.

Oldham and Boone, two of Kentucky’s wealthiest counties, continue to be the top two for health outcomes, as they have been since the rankings began in 2011. No. 3 Shelby County, which borders Oldham, has been in the top five since 2013. Adjoining Spencer County is ranked fourth. Calloway County (Murray) in Western Kentucky took the fifth spot this year, replacing Bullitt County, which dropped to No. 9.

Oldham and Boone are also the top two counties in health factors, and have been since 2015. They have been in the top five since 2011. Woodford, Campbell and Scott are currently ranked third, fourth and fifth, respectively.

Owsley, Perry, Breathitt, Bell and McCreary counties, in that order, are the bottom five in outcomes. All are in the Eastern Kentucky Coalfield. Wolfe County, which has been in the bottom bunch since 2016, moved to No. 113, an insignificant change. The bottom five counties for health factors are Clay, Owsley, Harlan, Lee and Wolfe, all in the eastern coalfield.

Some counties show big changes

Several counties moved up more than 10 notches to make it into the top quartile for health outcomes. Hickman County, the only Kentucky county that borders Fulton County, moved up 26 slots to rank 17th. Edmonson County moved up 15, to rank 18th; Logan moved up 18, to 22nd; and McCracken (Paducah) moved up 21, to 26th.

Two counties dropped more than 10 slots to land them into the bottom quartile for health outcomes: Lewis is now 92nd, down from 74th last year, and Wayne is 91st, down from 77.

Two counties moved up more than 10 slots to make it into the top quartile for health factors: Bourbon, which moved to 28th from 51st, and Caldwell, which moved to 29th from 56th.

Carter County was the only one to drop more than 10 slots to fall into the bottom quartile for health factors, to 97th from 76th.

Livingston County saw the greatest drop in health outcomes this year, falling 42 notches, to 76th from last year’s 55th. It also dropped 25 slots in health factors, to 65th.

McLean County also saw a big drop in outcomes, falling 38 slots to 73rd. It dropped 21 slots in factors, to 56th.

Tiny Robertson County saw the greatest improvement in health factors, moving to a 36th from 75th last year. However, it saw an eight-notch drop in health outcomes, to 96th.

Another county that saw big drops in both outcomes and factors is Carlisle, just north of Hickman on the Mississippi. It had a 29-notch drop in outcomes, to 52nd, and a 14-notch drop in factors, to 41st. From 2014 to 2018, Carlisle had ranked between 21st and 27th for health factors.

For a table of counties with big changes, click here.

The report charges Kentucky counties to take this data and turn it into action, and offers specific strategies to do so on the “Take Action to Improve Health” section of its website. These strategies include, among other things, a link to evidence-informed policies and programs that are proven to work locally in the “What Works for Health” section.

Further, the measures in the rankings offer journalists a unique opportunity to see what is going on in their communities when it comes to health — both good or bad. And many Kentucky newspapers do just that.

In 2017, an analysis by researchers at the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues at the University of Kentucky found that 31 papers in 30 counties published 36 separate articles about the rankings in the five weeks after the rankings were released in late March. The researchers examined 106 of the approximately 140 paid-circulation newspapers outside Kentucky’s three major urban areas, covering 115 of the state’s 120 counties.