Ky. has 59 operating syringe exchanges and six in the wait; state drug-policy director credits public-health advocates for increase

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

Kentucky is lauded nationwide for its embrace of syringe exchanges to thwart the spread of HIV and hepatitis C among intravenous drug users, but getting them approved locally continues to be a challenge and generally only happens after months, or even years, of educating the public.

Van Ingram, executive director of the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy, attributed the success of Kentucky’s syringe exchanges to the ongoing efforts of the state’s public health workers, who promote the exchanges as “harm reduction programs.”

“It’s just great public health advocacy at the local level, who just wouldn’t give up,” Ingram said July 11 at a health-related forum in Covington.

He was speaking broadly about the state’s many efforts to battle the opioid epidemic, including a 2015 law that allows syringe exchanges with approval of the county health board and fiscal court and the legislative body of the city where the exchange is to be located.

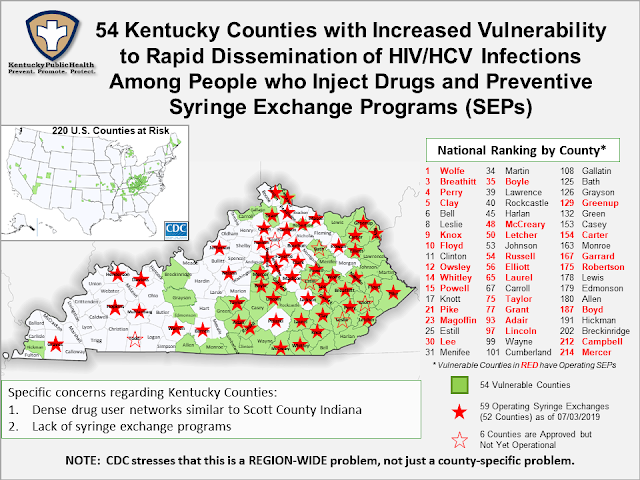

Kentucky has 59 operating syringe exchange locations in 52 of its 120 counties, with six more approved but not operational. Since mid-February, when Kentucky Health News did its last syringe exchange roundup, 11 additional counties have been marked on the state health cabinet’s map of exchanges.

Since February, Henderson, Hopkins, Taylor and Owen counties have been added to the map and are identified as operational locations. Magoffin County was also recently added, even though it opened last June, Hazard’s WYMT-TV reports.

Among the 54 Kentucky counties the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has identified as being the most vulnerable to outbreaks of HIV and hepatitis C among IV drug users, 33 have approved an exchange, with 29 of them operational.

The vulnerable counties that have not approved an exchange are Allen, Bell, Breckinridge, Carroll, Casey, Clinton, Cumberland, Edmonson, Gallatin, Grayson, Green, Harlan, Hickman, Johnson, Lawrence, Lewis, Martin, Menifee, Monroe, Rockcastle and Wayne.

Bath, Estill, Knott, and Leslie counties, which are included on the list of 54, were recently added to the exchange map, as have Todd County in Western Kentucky and Scott County in the Bluegrass region. These exchanges are marked as not yet operational.

State Sen. Whitney Westerfield of Hopkinsville “still thinks some of his colleagues are uneasy” about syringe exchanges, Max Blau reports for Stateline. “But he’s still hopeful that the results will mirror that of the CDC’s research, which shows that injection drug users who have access to syringe exchanges are five times more likely to get treatment than those who don’t.

“There’s not universal support, but we’ve moved in that direction,” Westerfield said. “I don’t see the people who hated [syringe exchanges] filing bills to reverse it. With harm reduction, there’s more general acceptance of it.”

Western Kentucky

Western Kentucky has been slow to adopt such programs, but that could be changing; three of the eight syringe exchanges west of Louisville are among the newest.

Henderson County’s exchange offers an example of the importance of persistent public health advocacy and education when it comes to getting these exchanges approved.

Douglas White details in his article for The Gleaner the many evidence-based arguments that Green River Health District Health Department officials presented at a January meeting of the Henderson City Commission meeting in support of a syringe exchange. He noted that the issue had been discussed on and off for several years and the exchange had been approved by the Fiscal Court, but needed the approval of the city, which finally happened in February.

Clayton Horton, the health department’s director, told Charles Taylor of the National Association of Counties about the importance of getting buy-in from the community.

“That required us to do a lot of education and do some advocacy with local governmental bodies,” he said. “We weren’t asking for resources; we’re weren’t asking them to pay for it. But we were asking them to consent and agree and to trust us and to trust the evidence-based practice to set these up and run them.”

Todd County’s exchange was approved June 14, Adam May reports for WHOP in Hopkinsville, and his story also spoke to the importance of public health’ leaders’ role in educating the community.

Magistrate Brent Spurlin said “he was initially skeptical and heard from people who believe the needle exchange is only a way to enable addicts, but he changed his opinion as he learned more,” May reports.

When Graves County opened its exchange in April, Mayfield Police Chief Nathan Kent told Chris Yu and Randall Barnes of Paducah’s WPSD-TV that he applauded the health department for opening the program, and that he believed it would not enable drug users — which is a common misperception.

“From our perspective, if folks come in here and take advantage of this opportunity, and they get the resources that convince them to make a change in their life, and they are able to overcome their addiction, then that’s just one more productive citizen,” Kent said.

Lauren Carr, the Graves County Health Department’s harm-reduction coordinator, told WPSD that the first person who came to the exchange for clean needles told her, “No one has treated me like a person before.”

“The whole goal of this program is to meet individuals where they’re at, but you can’t leave them there,” she said. “You have to give them the resources, the education, and the things that they need to make better choices for themselves.”

Hopkins County approved its exchange in April, Doreen Dennis reports for Surf KY News.

Cave City in Barren County was considering an exchange, but the city council voted unanimously against it, Gina Kinslow reported for the Glasgow Daily Times on Feb. 11. Barren County already has an exchange, in the county seat of Glasgow.

The middle of the state

The first sentence in Steve McClain’s Georgetown News-Graphic article about Scott County finally passing its syringe exchange sums up the challenges involved in getting many of these programs passed: “After months and months of tense debate and votes, Scott County’s syringe exchange program launches Monday, July 1, from noon to 4:30 p.m.”

And while there’s not much posted online about Owen County’s newly approved exchange, a December 2016 article in the Owenton News-Herald indicated that the Three Rivers District Health Department has been working on getting one there for years.

In another example of public-health persistence, the Anderson County Health Department proposed a syringe exchange three years ago and couldn’t gain the support from either the city or county — but in June of this year, the health board approved one, which now allows it to go before the city council and fiscal court, Ben Carlson reports for The Anderson News.

Taylor County approved its exchange in April. The Lake Cumberland District Health Department offers two educational videos about syringe exchanges to educate its community, one that addresses how syringe exchanges help with the cost of Hepatitis C and the other titled, “Why in the World Would You Give a Needle to a Drug Addict?”, shown below.

Exchange models vary

Ingram told the forum attendees, “When you’ve seen one syringe exchange program in Kentucky, you’ve seen one syringe exchange program in Kentucky.” While they all work toward what is commonly called “harm reduction,” they vary in their hours, locations and services offered.

One of the more unique set-ups is the use of mobile exchanges, which Laurel, Knox, Clay and Jackson counties will share. Whitley County, which has a stationary exchange, was supposed to join the program, but has decided to not participate, according the county health department.

WKYT-TV reported in April that Lexington’s program was expanding to two days a week, and since September 2015 has served more than 2,700 people, with an average of 175 coming in every Friday.

“The thing we are most proud of is 128 people have entered rehab through this service,” health department spokesman Kevin Hall told WKYT. “We have on-site counselors available to offer referrals into programs and so that is 128 people who get a second chance.”

Another evolution of these programs is that many of them now regularly distribute naloxone, a drug that can reverse an opioid overdose.

Terry DiMio reports for the Cincinnati Enquirer that at least 92 lives have been saved with naloxone that was handed out at two Northern Kentucky syringe exchanges. Since opening the two exchanges have handed out 1,358 naloxone kits, she reports.

Click here to get a list of all the exchanges and their hours of operation, as well as a list of facts about syringe exchange programs.