By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

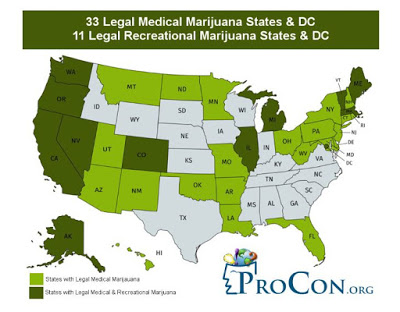

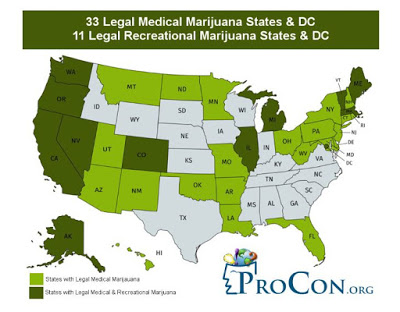

The health benefits of medical marijuana haven’t been proven and more research is needed, according to a leading researcher on the topic, but that hasn’t stopped 33 states from approving it. It’s still to be determined what will influence Kentucky lawmakers as they again consider passing such a law.

In the last legislative session, Kentucky legislators were able to get a bill to legalize medical marijuana out of committee. And though it wasn’t called up for a House vote so late in the session, and key Senate leaders are opposed to it, its sponsors have vowed to try again in January.

On Sept. 23 in Lexington, the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky held the first major conference in Kentucky about the issue, at its annual policy forum. “Medical Marijuana Fact and Fiction: Practical Public Health Policy Considerations for Kentucky” drew a sellout crowd of 360 to the Marriott Griffin Gate Resort in Lexington.

“If this is coming our way, shouldn’t public health, shouldn’t the medical community, shouldn’t the people who care about the welfare of the citizens of this state have an important voice and an important place at the table during these discussions?” asked Ben Chandler, president of the foundation. “I’m afraid that they might not have that place, if everybody puts their head in the sand.”

Chandler told the crowd that the forum was being held to look at the evidence regarding the public-health impact of legalized medical marijuana, increasingly known as cannabis (its biological genus).

“The Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky has not taken a position on the subject as yet, but what we do believe is this: whatever Kentucky ultimately decides to do, it ought to make that decision based on evidence,” he said.

What does the research say?

Nationally recognized researcher Shanna Babalonis walked through several peer-reviewed scientific studies and said medical research does not support using cannabis for chronic pain, nerve pain, as a replacement for opioids, opioid-use disorder, anxiety or depression.

“All of the research that we can use right now just doesn’t support it,” she said, noting that the study of pain is complex. “We’re not saying 100 percent that cannabinoids do not work for pain, it’s just we’re really limited in being able to demonstrate that,” she said. “But if you strictly look at the scientific literature, there’s really little to no signal that cannabinoids actually help . . . folks that have pain.”

However, she said we don’t have enough research on the medical benefits of marijuana because it is a Schedule I drug, meaning federal law classifies it as having no medical benefit. That means researchers need a special license to work with it, which involves a process that Babalonis described as “onerous.”

Asked about studies from other countries that dispute her findings, Babalonis said they are typically based on self-reported, anecdotal information. While such studies have value, she said, scientists and physicians are held to a higher standard, ones that require randomized, well-controlled, well-executed, placebo-controlled methods of research.

Studies have suggested the presence of medical marijuana in a state reduces the number of opioid doses prescribed in it, and that opioid-overdose deaths have declined by 25 percent in such states, but Babalonis said such population-based studies are limited and don’t dig deep enough into what is or may be causing these declines.

For example, she said, they don’t show the relationship between those who use marijuana and those who have an opioid prescription. Nor, she said, do they account for other factors that influence opioid use and overdose deaths, like prescription monitoring programs, laws that address opioid prescribing, or access to Naloxone, a drug that reverses opioid overdoses. Also, she said more recent population-based studies show the opposite effect, that medical marijuana laws increase overdose deaths.

“There is no evidence that suggests cannabis can help with any aspect of the opioid crisis,” Babalonis said. “We know virtually nothing about the interactions between the two, or how they come together to influence addiction and drug misuse.” She added later, “I think it’s really safe to say that it’s absolutely reckless to suggest that cannabinoids are going to be the answer for the opioid crisis.”

She concluded, “I think we just need to carefully consider what conditions will be permitted and what products will be permitted.” Babalonis is an assistant professor at the University of Kentucky medical school, in its Center on Drug and Alcohol Research. She has a doctorate in behavioral neuroscience and psychopharmacology.

What’s happening in Colorado?

The keynote speaker at the forum, Andrew Freedman, oversaw Colorado’s legalization of marijuana for both medicine and recreation. He talked about the impact of legalizing marijuana on a variety of public-health aspects. He now works at Freedman & Koski, a cannabis consulting firm, which he co-founded. Colorado is one of 11 states that allow recreational marijuana.

In essence, Freedman told the group that young people’s use of marijuana in Colorado hasn’t really changed since legalization, while adult use has.

He said past 30-day use among 12- to 17-year-olds increased slightly after it was legalized in 2012, from 10.5% to 11.2%, then peaked at 12.6% after the first stores opened in 2014, but has since decreased to 9% in 2016-17. The national rate in 2016-17 was 6.5%. This data came from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration‘s National Survey on Drug Use and Health.

Among adults in Colorado, from 2016 to 2017, use in the past 30 days increased in most age groups, from 13.6% in 2016 to 15.5%. That was largely driven by a rise in use among 18- to 34-year-olds. The report also shows that Colorado adults are using marijuana more frequently, with adult daily or near-daily use increasing from 6.4% in 2016 to 7.6% in 2017.

Freedman noted that there is likely some “observation bias” in those figures because people are more willing to admit use of marijuana since it is now legal to do so for any purpose.

The latest Gallup Poll found that 79% of Americans who oppose making medical marijuana legal say that the risk of increased car accidents underlies their opposition.

Freedman said in Colorado, fatal crashes involving marijuana have steadily increased over the years, from 47 in 2013 to 133 in 2017. He noted that Kentucky’s death rate from all automobile accidents is well above Colorado’s rate and the national rate.

Other key findings in the state report that were not mentioned include a slow upward trend of unintentional consumption among children under the age of 9, as well as related emergency-room visits. Freedman said Colorado has since changed its packaging requirements to require the manufacturer to use childproof, resealable packaging and that this has helped.

What’s next?

Freedman, like Chandler, encouraged the attendees to put aside their feelings about whether legalizing medical marijuana was a good idea or a bad idea, but to instead think about how to manage it from a public-health perspective in case it were to go forward.

In particular he encouraged efforts to restrict advertisements for marijuana, with a focus on making sure vulnerable populations aren’t targeted.

All that said, some in the the medical community are pushing back. Dr. Danesh Mazloomdoost, with Wellward Regenerative Medicine, took issue with calling marijuana a medicine, stating that medicine is used to treat a specific condition with a specific dosage, and offers contraindications for people who should not be taking it — and marijuana does not have such guidelines.

“As the medical community . . . the universal stance is that we don’t feel comfortable as a clinician body to endorse marijuana as a medication,” he said.

Mazloomdoost said he personally thought it should be labeled for what it is, a vice.

Freedman agreed: “I personally advocate for the broad public-health framework to be cannabis as an intoxicant. I think that does the best at preventing driving while high, preventing substance abuse, really looking at it from the government perspective, as this is an intoxicant that your people are taking and then they’re in society.”

He added, “We need a path forward to allow for sympathetic patients to continue to have access to cannabis, while the FDA catches up with research, because I think what we’re hearing in polling, what we’re hearing in the legislature is people are just simply tired of waiting.”

Jaimie Montalvo is one of those patients. He has multiple sclerosis, is a cancer survivor and says he has found relief for his conditions with cannabis. Montalvo is also the executive director for

Kentuckians for Medical Marijuana, a nonprofit working for patients to have access to marijuana without fear of prosecution. Montalvo participated in a panel at the forum, explaining the medical cannabis bill that he said will be filed.

Montalvo said in a telephone interview that Kentucky needs to pass a law to allow medical marijuana in Kentucky primarily for public safety. He pointed out that many Kentuckians have experimented with cannabis for their health conditions and found relief, usually after exhausting traditional medications that have either not worked, not worked sufficiently or have resulted in unwanted side effects.

“We need to make sure that what these patients are consuming is clean, is properly tested and is being sold in a safe environment,” he said.

Things to consider

Freedman said Colorado also struggles with drug cartels that have come into the state and taken advantage of its home-grow rules and the overall lack of regulation. He said many are growing cannabis in Colorado and selling it out of state because they get $800 a pound in Colorado and $3,000 a pound in unlisted states.

Another challenge is potency. “THC concentrations are sky high,” said Babalonis. THC stands for tetrahydrocannabinol, the psychoactive ingredient in marijuana.

In the 1970s marijuana had a THC content of 1% to 2%, while today’s products are around 17%, with dab and wax products closer to 80% or higher, she said. She added that medical marijuana is between 15% and 20%.

Freedman agreed, saying, “Potency is one of those areas that nobody knows what to do with right now. . . . We don’t have a public-health framework for what is too potent, and what is not too potent.”

Babalonis said, “One key thing that I just wanted everyone to take away from this meeting today is that there is not real differences in the products and in the plant material that is available for medical use versus recreational use . . . It’s almost exactly the same. There’s nothing special or protective about medical marijuana versus recreational marijuana.”

And while marijuana use does not produce overdose or death in adults, it can be highly toxic to children and animals, she said.

Beau Whitney, with New Frontier Data, which provides data about the cannabis industry, told reporters that 480,000 Kentuckians have used marijuana in the past year, with a total market value of $800 million.

The latest Kentucky Health Issues Poll on this topic was conducted in the fall of 2012. It found that 78 percent of adults supported the use of medical marijuana if their doctor recommended it; 26% supported it for recreational purposes; and 38% approved it under any circumstances.

The latest Gallup poll on the topic, taken in May 2019, found that 64% of Americans favor legalizing cannabis for recreational purposes, with 86% of that group saying medical use of the product was a very important reason for their support.