Federal appeals-court judges indicate they are unlikely to revive Bevin plan for work requirements in Medicaid

Federal judges were dubious Friday of Republican Gov. Matt Bevin’s campaign to add work requirements to the Medicaid program, as they heard an appeal of rulings that have blocked it.

“People are going to lose coverage … and you haven’t addressed that,” Judge Harry Edwards told Trump administration lawyers during oral arguments at the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in Washington.

Edwards and the other two judges asked how the plan would “fulfill the central objective of Medicaid, which is to ensure health coverage to the nation’s most vulnerable citizens,” reports Deborah Yetter of the Louisville Courier Journal.

“The government argued that in order for states to maintain a certain level of quality of coverage for everyone, states can compel able-bodied adults that are covered by Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to work for a certain amount of time each month to promote general physical health and financial stability,” Alexandra Marquez reports for the Lexington Herald-Leader.

The law doesn’t allow “states to make people prove they are working in order to keep coverage, said Judge David Sentelle, brushing aside arguments from the states that requiring people to prove they are working or volunteering could make them more engaged in their communities and become healthier,” Yetter writes.

Sentelle was appointed by Ronald Reagan, and Edwards by Jimmy Carter. Judge Cornelia Pillard, a Barack Obama appointee, “questioned claims by states and the Trump administration that the changes could help make people healthier and move from Medicaid to commercial insurance,” Yetter reports:

“Where is the evidence that this kind of stuff is even plausibly going to have that effect?” she asked Alisa Klein, a U.S. Justice Department lawyer representing the Trump administration, which has approved such plans in nine states and has 10 more requests pending.

“It is very difficult to prove causation,” Klein said.

“Indeed,” replied Pillard dryly, triggering a burst of laughter in the packed courtroom.

Bevin wants to require “able-bodied” Medicaid members without children to spend 80 hours a month working, going to school or taking job training, and report their hours monthly. His administration has estimated that in five years, the state’s Medicaid rolls would have 95,000 fewer people with the rules than without them, with noncompliance being one of the main reasons.

Kentucky was the first state to get work requirements approved, but a lower-court judge blocked its plan and one that had already taken effect in Arkansas.

“There is no set date for a judges’ ruling on the case, but the Justice Department has asked for an expedited decision,” Marquez reports. “Depending on the decision, the suing Kentucky and Arkansas residents or HHS will have the option to appeal the case to the entire D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals or directly to the Supreme Court,” either of which can refuse to hear the case.

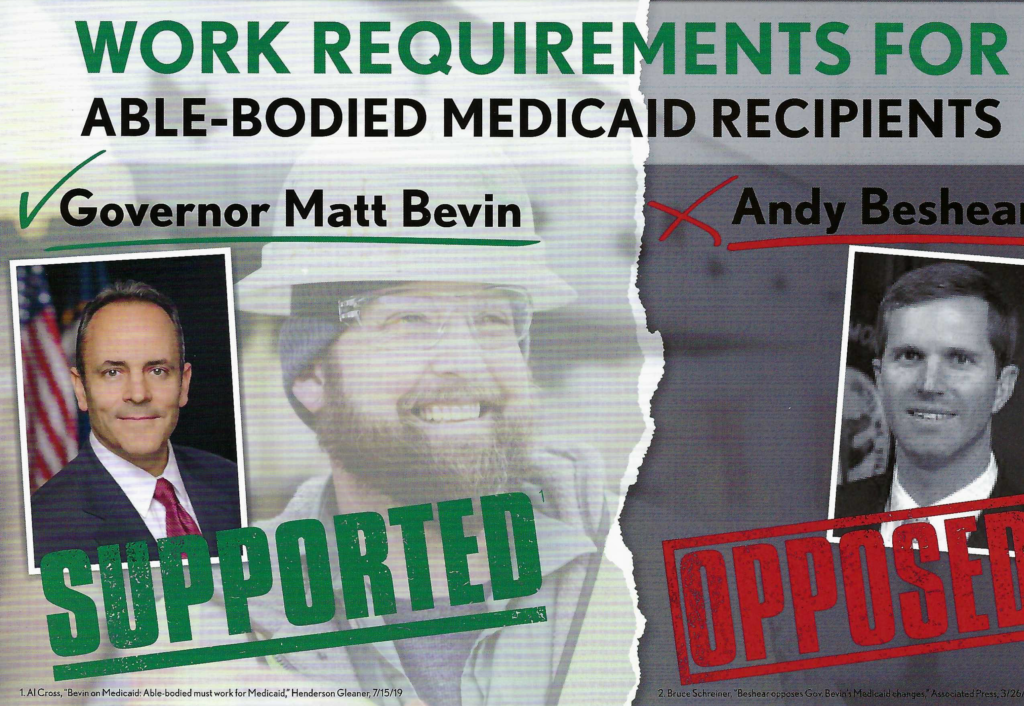

Bevin has said he expects the Supreme Court to decide the issue. He has issued an executive order that would end the Medicaid expansion six months after a final ruling against his plan. His opponent in the Nov. 5 election, Attorney General Andy Beshear, has promised to drop the work rules.

Beshear’s father, then-Gov. Steve Beshear, used the 2010 reform law in 2014 to expand Kentucky Medicaid to about 500,000 people with incomes less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. That limit is $23,336 for a couple and $35,535 for a family of four. The federal government pays 90 percent of the expansion’s cost, and about 70 percent of the cost of traditional Medicaid.

The Trump administration is giving states hundreds of millions of dollars to implement work rules. The General Accounting Office of Congress said Thursday that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is “not conducting adequate oversight” of the money, but “CMS rejected GAO’s recommendation to consider the administrative costs of such programs when looking at whether [they] are budget neutral,” which the law requires, James Romoser reports for Inside Health Policy.

“Work requirements may cause significant increases in Medicaid administrative costs as states seeking to adopt the policy update their eligibility and enrollment systems, educate beneficiaries, train staff, and develop ways to monitor compliance,” Romoser writes. “According to GAO, CMS officials said the agency did not review the Kentucky contract and approved Kentucky’s request based on the state’s assertion that the costs were specific to technology.”

Kentucky’s budget of $271 million for the work (more than $100 million of which has been spent, 87 percent of it federal money) is much larger than the five other states examined by the GAO. That’s apparently because it presumes that the plan would affect 620,000 Medicaid members, a much higher number than previously published. The GAO report, which includes many details about the programs in the five states, says the figure includes people who might qualify for an exemption, so it could reflect the total number of expansion members over three years; tens of thousands of members go on and off the program each month.