More action needed to protect patients from antibiotic-resistant infections, which kill an American every 15 minutes, CDC says

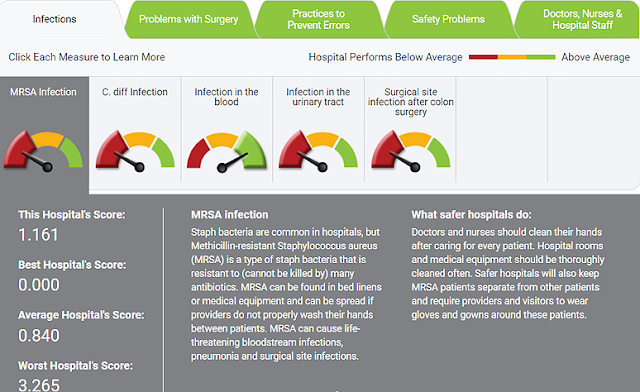

The University of Louisville Hospital got a D overall in the Leapfrog Group’s patient-safety ratings and was rated poorly in dealing with one of the major antibiotic-resistant infections, Methicillin-resistant staphlycoccus areus (MRSA), and C. diff, an infection related to the use of antibiotics. Click to enlarge.

—–

More action is needed to protect Americans from antibiotic-resistant infections, 2.8 million of which occur in the U.S. each year, killing more than 35,000 people, one about every 15 minutes, says the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

On top of that, 12,800 people died from an infection that is not drug-resistant but is “caused by the same factors that drive antibiotic resistance—antibiotic use and the spread of germs,” the CDC said in its report, Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States, 2019. “The number of people facing antibiotic resistance is still too high. More action is needed to fully protect people.”

Hospitals are a main battleground in the fight. The word “hospital” appears 188 times in the 148-page report, which was issued days after the Leapfrog Group‘s latest rankings of patient safety at hospitals nationwide, including 50 in Kentucky. The most common grade, on an A-to-F scale, was a C, and the report showed that many hospitals had difficulty dealing with resistant infections.

The report’s foreword, by CDC Director Robert Redfield, sums up the history of antibiotics in personal terms: “In March 1942, Mrs. Anne Miller of New Haven, Connecticut, was near death. Infectious germs had made their way into her bloodstream. Desperate to save her, doctors administered an experimental drug: penicillin, which Alexander Fleming discovered 14 years earlier. In just hours, she recovered, becoming the first person in the world to be saved by an antibiotic. Rather than dying in her thirties, Mrs. Miller lived to be 90 years old.

“Today, decades later, germs like the one that infected Mrs. Miller are becoming resistant to antibiotics. You could have one in or on your body right now—a resistant germ that, in the right circumstances, could also infect you. But—unlike the bacteria that threatened Mrs. Miller—the bacteria may be able to avoid the effects of the antibiotics designed to kill them. Unfortunately, like nearly 3 million people across the United States, you or a loved one may face an antibiotic-resistant infection.”

The use of antibiotics has a self-defeating element: the growth of genetically different bacteria and fungi that have mutated into forms that are resistant to the antibiotics or picked up resistance traits from other germs through mobile genetic elements. Also, antibiotic use encourages development of Clostridioides difficile, or C. diff., a bacterium “that can cause symptoms ranging from diarrhea to life-threatening inflammation of the colon,” says the Mayo Clinic. The CDC report says 223,900 cases of C. diff. occurred in 2017, killing at least 12,800 Americans.

“Dedicated prevention and infection control efforts in the U.S. are working to reduce the number of infections and deaths caused by antibiotic-resistant germs, but . . . CDC is concerned about rising resistant infections in the community, which can put more people at risk, make spread more difficult to identify and contain, and threaten the progress made to protect patients,” the CDC said in announcing the report. “The emergence and spread of new forms of resistance remains a concern.”

What is to be done? “Public-health prevention programs targeting resistant germs can and have worked to slow spread and save lives, but more needs to be done,” the report says. “The U.S. and global community must scale up these effective strategies and develop new strategies to prevent infections and save lives. In the United States, infection prevention activities have proven effective in slowing the spread of resistant germs. This includes:

- Strategies to decrease spread within healthcare settings (e.g., implementing hand hygiene)

- Vaccinations

- Implementing biosecurity measures on farms

- Responding rapidly to unusual genes and germs when they first appear, keeping new threats from spreading