New nutrition labels use larger portion sizes and list added sugar, which can cause many health issues; here are ways to limit it

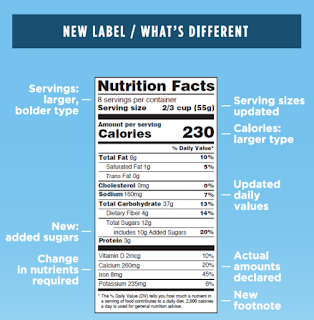

Nutrition fact labels are the primary source of information about what’s in the food we eat, and they recently got their first update in 20 years.

The Food and Drug Administration says it based the changes on “updated scientific information, new nutrition and public health research, more recent dietary recommendations from expert groups, and input from the public.”

Manufacturers with $10 million or more in annual sales were required to switch to the new label by Jan. 1, those with less annual food sales have another year to comply.

One of the biggest changes on the labels is that they now show a serving size based on the amount most people eat and drink, instead of a suggested serving size.

This change was made to reflect the larger portions people eat and drink now, compared to those in 1993 when the previous size requirements were published. For example, the new serving size for ice cream is 2/3 cup, compared to 1/2 cup on the old label.

And for products that could be consumed in one sitting, like a 24-ounce bottle of soda or a pint of ice cream, manufacturers must now provide a “dual column” label to show calories and nutrients for both “per serving” and”per package” amounts.

The labels also show the calories and serving size in larger and bolder type. This change was made to address the growing obesity problem in the United States, which is associated with heart disease, stroke, certain cancers and diabetes.

The new labels will no longer include calories from fat, but will instead show the types of fat a product contains. This change was made to reflect research that shows the type of fat you consume is more important than the amount.

The labels now include potassium and Vitamin D, along with calcium and iron. Vitamins A and C have become optional for listing, since most Americans get enough of those nutrients in their diets. They also reflect updated requirements for the amount of nutrients we need, shown in both the actual amount and the percent daily value. An updated footnote explains the meaning of percent daily value.

The FDA added Vitamin D and potassium because research shows these are nutrients that Americans don’t always get enough of, and when lacking, are associated with increased risk of chronic disease.

Added sugars have also been added to the label. The most recent dietary guidelines recommends you consume less than 10% of your daily calories from added sugars.

The American Heart Association recommends no more than six teaspoons of added sugar per day for women and nine teaspoons for men. The recommended rate for children varies between three and six teaspoons per day, depending on age and caloric need. One teaspoon of sugar equals four grams on the label.

Health risk of added sugar

Most people have no idea how much added sugar they consume, because it’s in nearly 70% of packaged foods and is found in breads, health foods, snacks, yogurts, most breakfast foods and sauces. Tara Parker-Pope reports for The New York Times. She says the average American eats about 17 teaspoons of added sugar a day — not counting the sugars that occur naturally in foods like fruit or dairy products.

A physician who was one of the first to raise the alarm about the health risks of added sugar told Parker-Pope that it’s not just about the added calories, but also about the many health risks that come with eating too much added sugar.

A physician who was one of the first to raise the alarm about the health risks of added sugar told Parker-Pope that it’s not just about the added calories, but also about the many health risks that come with eating too much added sugar.

“It’s not about being obese, it has to do with metabolic health,” Dr. Robert Lustig, professor of pediatric endocrinology at the University of California, San Francisco, told Parker-Pope. “Sugar turns on the aging programs in your body. The more sugar you eat, the faster you age.”

Parker-Pope writes that while many scientists believe added sugar is the leading culprit in the obesity epidemic, they also say that even people of normal weight can suffer the same health problems associated with eating too much sugar, including heart disease, Type 2 diabetes, cancer, stroke and even Alzheimer’s disease.

Too much added sugar can also damage your liver, similarly to the way that alcohol does, leading to a condition that is called “sugar belly,” in which your waist is bigger than your hips.

Parker-Pope points to the difference between the sugar, or fructose, found naturally in foods, which are good to eat, and those that have been added to foods.

She writes that our bodies can handle fructose when it’s eaten as a whole fruit because it comes with a number of micronutrients plus fiber, which slows the rate at which the sugar enters your bloodstream. But when we eat the fructose found in ultra-processed foods and beverages, it doesn’t have the fiber to slow it down and “your body gets a big dose of fructose that can wreak havoc,” she writes.

Further, she reports that high consumption of processed fructose can result in a dulled response to a hormone called leptin, which is a natural appetitie suppressant, leading to weight gain and that it can create changes in the brain similar to those found in people who are addicted to cocaine and alcohol.

Gary Taubes, author of The Case Against Sugar and an advocate of low-carbohydrate eating, doesn’t agree with the food industry’s recommendation that added sugars be consumed in moderation.

“If I start to allow sugars into my life, there is a slippery slope,” Taubes told Parker-Pope “I think for many people, getting control of their sugar habit is the most important thing they can do for their health. If they can’t do it through abstinence, then mostly-abstinence is a good thing to achieve.”

The New York Times has offered a 7-Day Sugar Challenge to help people reduce the added sugar in their diet. For example, the first day in the challenge offers tips on how to cut out sugar from your breakfast. Parker-Pope stresses that it’s not easy, and the cravings for sweets will be worse in the first five days — but the payoff is worth it.

Lustig recommends three weeks of no added sugar to get your brain’s dopamine system back to normal. “Then you can introduce something back in,” he told Parker-Pope. “But it’s got to be under your control, not the food industry’s control.”