Pandemic has thwarted vaccinations; many vaccine-preventable illnesses are more deadly to kids; schedule shots now, doc says

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

Some Kentucky children have likely fallen behind in their routine immunizations because of the disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic, putting them at risk for measles, whooping cough and other life-threatening illnesses. Health experts say now is the time to get them caught up.

“The risk of vaccine-preventable illnesses has not gone away due to the covid-19 situation and it is just as important now, if not more so, that we make sure that our children are protected from all of the infections that we can,” said Dr. Sean McTigue, medical director for pediatric infection prevention and control at Kentucky Children’s Hospital.

McTigue said many parents are afraid to bring children to a doctor’s office to get them vaccinated out of a fear of exposing them to the coronavirus, often not realizing that the illnesses prevented by vaccines can be more deadly to children than the virus.

“Unlike covid-19, the vaccine-preventable illnesses that we are talking about are the ones that are the most deadly for our infants and our young children,” he said. “Covid-19 is actually something that is not a big concern for young children. Younger children, specifically those less than 10 years of age, are far less likely to catch covid-19, to be positive for it, and are far less likely to have any serious consequences from it.”

As of June 6, the state’s covid-19 daily report showed that 234 children under 10 had tested positive for the virus, and one infant had died from it. However, Health Commissioner Steven Stack said June 3 that if not for the pandemic, the death would have been attributed to Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, but is counted as a covid-19 death because the infant tested positive for the virus.

The report does not show how many children have ever been tested for the virus. Four Kentucky children have developed a multi-system inflammatory syndrome that is linked to the virus, and all have recovered.

|

| Dr. Sean McTigue |

McTigue said most doctor’s offices have established practices to minimize the risk of exposure to the virus, like doing well-child visits in the morning and sick visits in the afternoon, or virtually; rigorous sanitation practices; and having patients wait in their cars instead of a waiting room.

“The risk of covid-19 infection and especially the risk of any serious consequences of covid-19 to children is very, very small,” he said. “Health-care providers are really doing everything that they can to take that very small risk and make it even smaller, such that it really is very safe to bring your child to the doctor and have them immunized right now.”

He stressed that it is especially important for children under the age of two to catch up on their immunization schedule, because they are supposed to have so many in those first two years.

“For a child who may have been born in the month or two preceding the health emergency, you could have a child who has received essentially no vaccines and is really unprotected against many infections that are quite deadly and are fully preventable by vaccine,” McTigue said.

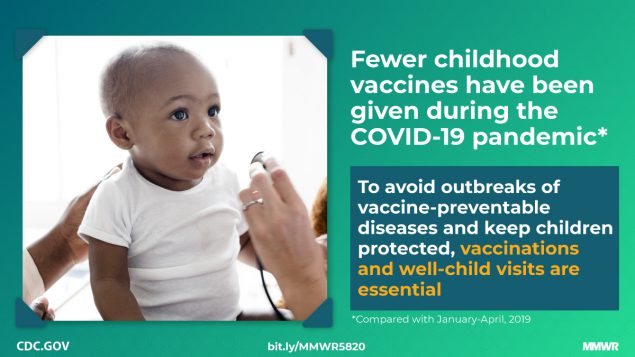

This is an issue across the nation, causing a concern that there could be disease outbreaks.

A study from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found sharp declines in orders for regular childhood vaccines, and in the number of measles vaccinations given since late March, about a week after the coronavirus was declared a national emergency. And while those drops are most notable in older children, they were also high in those under the age of 2.

The report warned, “The identified declines in routine pediatric vaccine ordering and doses administered might indicate that U.S. children and their communities face increased risks for outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases.”

The study looked at vaccine doses ordered by doctors in the the federally funded Vaccines for Children Program, which covers about half of U.S. children under 18, between mid-March, when the national emergency was declared, and mid-April. It found that about 2.5 million fewer orders than in the same period in 2019, and that the number of measles vaccinations given to children dropped from an average of about 5,000 per week before mid-March to about 1,300 per week the following month.

“What that really indicates is that we have a lot of children who are now either un-vaccinated or under-vaccinated depending on where they were at in the vaccine schedule when that change happened,” McTigue said about the study.

McTigue said university medical practices have also seen drops in their vaccination rates, despite the fact that they have been open and providing care throughout the pandemic. Health-care clinics and medical offices across the state were allowed to reopen April 27.

Dr. Sally Goza, president of the American Academy of Pediatrics, also urged parents to get their children’s vaccines caught up.

“Immunizing infants, children and adolescents is important, and should not be delayed,” she said in a statement. “As social distancing restrictions begin to lift around the country and people begin to circulate, children and teens who are not vaccinated will be at higher risk for contracting a disease that could be prevented by a vaccine.”

Kentucky is working toward reopening schools in the fall, under rules that will call for social distancing, among other things. But public-health officials caution that social distancing offers little protection, particularly from the measles and pertussis, the medical name for whooping cough, and both diseases are much more contagious than the coronavirus.

Without any interventions, a person with measles will infect nine out of 10 people around them if they are not protected, and a person with pertussis can infect 12 to 15, according to the CDC. A person with the coronavirus, without any interventions, is estimated to infect three more.

Immunizations also provide “herd immunity,” which occurs when enough people have been immunized against a disease to protect others who are not immunized. Some can’t get vaccinations because their immune systems are too weak to allow them to get shots, or because they are too young.

McTigue said it is pretty easy to lose herd immunity when you have such a big change in vaccination rates, “which is what we are really seeing now,” as opposed to the slow drop in rates that results from vaccine refusal that has happened over the past decade, which he said impacts herd immunity more slowly.

“Now we’ve got a large segment of the population of young children who are un-immunized or under-immunized, and that absolutely will affect herd immunity and put not only those children at risk, but also the other people that they are exposed to who may not be able to be vaccinated because of their own medical issues.”

Kentucky’s schools require students to provide up-to-date immunization records at the beginning of each school year, unless exempted for religious or medical reasons.

McTigue urged parents to make appointments to get their children vaccinated now, because providers have fewer daily patient spots to accommodate all of the new covid-19 rules and any last-minute rush to get children immunized in August before school starts could result in a further delay in your child’s vaccination schedule.