“Communities are hesitant, and we do understand their concerns, but I would encourage any and all communities to educate themselves, along with their policymakers and even the citizens in the community, to find out exactly what a harm reduction/syringe exchange program is really all about,” he said. “It is about getting dirty needles off the street and off of our playgrounds and off of the places we go, certainly that’s a huge part of it. But it is also a program that is about helping the people in our community as well that need help because they are addicted to drugs. Be open minded and get educated.”

Such programs have been able to stay open through the pandemic because the Department of Public Health designated them an essential service.

“To ensure public safety, programs adopted strategies including face coverings, moving to outside stations, creating distance in their spaces, some appointment-only programs, limiting hours/days and decreasing number of infectious-disease testing times,” the department said in an e-mail.

Harm-reduction programs are designed to prevent outbreaks of HIV and hepatitis C, which are commonly spread by the needle sharing among intravenous drug users. They also provide health screenings and vaccines, and connect drug users to treatment.

They were approved in Kentucky under a 2015 law that requires approval by the county health board, the fiscal court and the city where the exchange is to be located.

Five added since last round-up

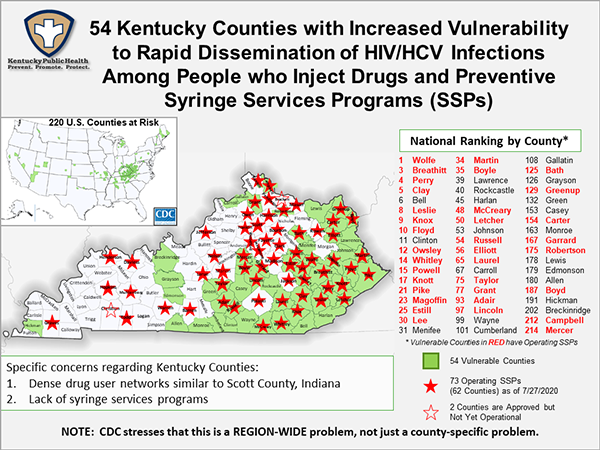

Kentucky has 74 operational syringe exchange locations in 63 of its 120 counties. Since mid-July 2019, when Kentucky Health News did its last syringe exchange

roundup, five more counties have been marked on the state Cabinet for Health and Family Services map of exchanges and the counties deemed most vulnerable to HIV and hepatitis C outbreaks.

Besides Bracken, the new counties are Christian, LaRue, Marion and Martin.

|

| Bracken County Health Department photo on Facebook |

Christian County’s program is the latest to be approved, but is not yet operational. Bracken County’s exchange is still marked as not yet operational on the state’s map, but it started operating July 8.

Among the 54 Kentucky counties that the

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has identified as being most vulnerable to outbreaks of HIV and hepatitis C among IV drug users, 34 have operational exchanges.

The vulnerable counties that have not approved an exchange include Bell and Clinton, which rank sixth and 11th on the national list of 220 vulnerable counties; Cumberland, Casey, Edmonson, Harlan, Johnson, Lawrence, Lewis, Menifee, Monroe, Rockcastle and Wayne, also in Appalachian Kentucky; and eight in the rest of the state: Carroll, Gallatin, Green, Breckinridge, Grayson, Green, Allen and Hickman.

Harm reduction and the pandemic

Christie Green, public health director of the Cumberland Valley District Health Department, said their program saw a brief dip in participation in March and April, and it has since increased. Early in the pandemic they only offered services every two weeks as a way to limit interactions, she said, but have since gone back to their weekly schedule.

“As restrictions were lifted,” she said. “most of our participants preferred to come every week.”

Green said they also increased usage of their mobile harm-reduction unit in Clay and Jackson counties. “So, instead of bringing them into the van, which is set up kind of like a little lab on the inside, we shifted it all to outside, under a canopy with a table beside the van,” she said. “If someone wants a test, then we mask them and bring them inside.”

Scott Lockard, public health director of the Kentucky River District Heath Department, which has a program in each of the seven counties in the district, said its use has held steady or better.

“People are still thankfully coming in and getting the supplies they need, because the last thing we would have wanted to see was a big uptick in HIV or hep C right now too,” he said. “Our services are being utilized more than ever.”

John Moses, harm-reduction team leader at the Lexington-Fayette County Health Department, said it has seen a steady increase in participation, with record numbers in the last month.

“The good thing about our program is that we were able to continue all of our services through the syringe exchange with really minimal interruption because of covid,” he said. “We simply moved our program outside and are using our mobile unit to see our clients.”

Jamey Whaley, harm-reduction and peer-support specialist with the Buffalo Trace District Health Department, said that one of the biggest changes he’s seen in its program since the beginning of the pandemic is a shift from methamphetamine to heroin, because limited meth supply has driven its price up.

“So I have seen more people who have gone in the direction of heroin, which is a little unsettling because of the risk of potential overdose,” Whaley said. He added that he has seen some of the program’s former participants relapse since the pandemic hit, and that he has added a good number of new participants.

Whaley said Buffalo Trace shut down its program down for six weeks at the beginning of the pandemic and re-opened in mid-May. Since then, “I’ve been very busy, especially the last month I have really been steady.”

Only a few in the works

Logan County has received approval from its Board of Health for a syringe exchange program, but still needs the approval of the Russellville City Council and the county Fiscal Court.

Alexis Bigham, who was the public-health educator at the

Barren River District Health Department when interviewed, and now works on harm reduction in Edmonson County through the

University of Kentucky, said two of the district’s eight counties (Warren and Barren) have exchanges.

The agency wants Logan to be next “because we have a lot of people traveling from Logan County to here in our Warren County program.” she said. But the pandemic has put that push on the back burner because everyone at the health department has been working on covid-19.

The Lincoln Trail District Health Department is based in Hardin County, but its efforts to start a program there haven’t been successful. In the meantime, Marion and LaRue counties have joined adjoining Nelson County in the program, largely due to local support, said Melissa Phillips, a harm-reduction specialist.

“You really need both pieces, you need your buy-in from your policymakers, and data is usually what sells them, and knowing that there is no cost associated with it,” she said. “And when you have a local champion, it makes the process so much smoother. They really do a lot of the leg work for us.”

She said the need in Hardin County is supported by data on drug arrests, HIV and hepatitis C, but the pandemic has slowed the effort, largely because they aren’t able to participate in face-to-face meetings with policymakers and the community, which she said is an essential part of the process.