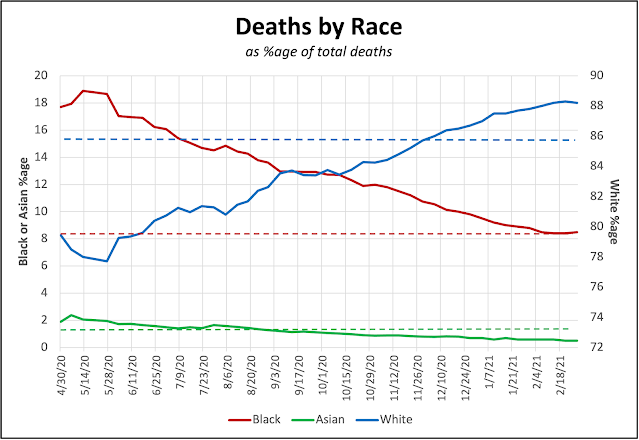

Graph by Bruce Maples (click to enlarge); dashed lines show races’ share of state population.

—–

Kentucky Health NewsAs the coronavirus pandemic took off, there was a striking anomaly in the data: African Americans were being infected, and dying, at a rate much greater than their share of the population.

The difference was so great, and so striking, that it drew frequent comment from Gov. Andy Beshear in his daily press conferences. A month into the pandemic, on April 11, he announced that Kentucky Blacks were dying of Covid-19 at a rate two and a half times their 8.4% population share; they were 21% of the deaths in which the person’s race was known (81% of cases at the time).

|

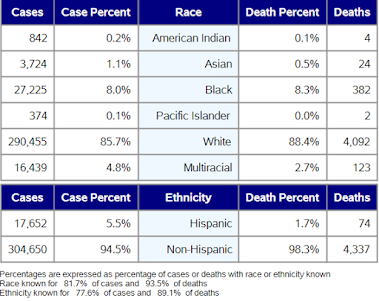

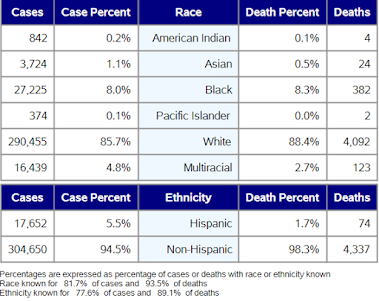

| Graph by Bruce Maples; dashed lines are races’ share of state’s population. |

Over the past year, however, the proportion of Blacks in the daily case and death numbers have steadily declined, to the point that they are now roughly the same, or less than, their share of the population.

At the same time, white Kentuckians’ shares of Covid-19 deaths have steadily climbed and are now greater than their share of the state’s population. Whites’ share of cases also rose.

Meanwhile, Asian Americans’ share of Covid-19 deaths in Kentucky is now less than their share of the population, reversing the pattern from early in the pandemic, when they were affected by some of the same factors as African Americans, one health expert said.

Dr. Sarah Moyer, director of the Louisville Metro Department of Public Health and Wellness, said many persons of color are “essential workers,” often in customer-facing industries such as restaurants and grocery stores, and thus could not work from home. So in the early days, while many people were able to be “healthy at home,” the Black and Asian populations in the state had to go into work, and thus were more at risk.

But as things began opening up, white institutions have been more aggressive about doing so, Moyer said: “More white churches went to in-person services. Black churches tended to stay remote. More whites started traveling. And, it’s been largely white-majority schools that have pushed to get back into the classroom.

“And, it’s just anecdotal, but it seems to me that whites are more willing to take risks.”

|

| State’s latest report on cases and deaths by race and ethnicity |

Donna Arnett, dean of public health at the University of Kentucky, said she suspects the early infection rate among people of color led to some “acquired immunity.”

“I don’t want to use the term ‘herd immunity,’ because we aren’t clear on just where that line is,” Arnett said. “But I do think that the large number of infections could have led to acquired immunity in that population.”

She added, “An Indiana study showed that for every reported case, there are about 10 more cases that are not reported and not counted. So, that early spike we see on the graphs actually represents an even larger spike of cases, which may have affected later infections.”

In Louisville, Moyer noted most of the people under 60 who are dying of Covid who are under 60 are Black or Hispanic.

One thing that has seemed clear over the past few months is that the rate of infection has dropped in the urban areas in the state, and increased in the rural areas.

The pandemic was later in getting to rural areas, but when it did, it found a vulnerable population that was sicker, older, and has less access to health care, several reports have noted.

|

| WFPL graph shows higher rates of new coronavirus cases in rural counties and one health district. |

For example, Louisville’s WFPL reported Dec. 23 that the November death rate in the Kentucky River Health District was 107% higher than the statewide rate, so deaths there were 4% of the state total though the district has only 2% of the state’s population. Out of 120 counties in Kentucky, only 18 had higher death rates in November than those comprising the Kentucky River district, based in Hazard.

|

| Daily Yonder graph |

This trend is national. The Daily Yonder does a weekly look at coronavirus cases and Covid-19 deaths in the rural U.S. Its latest graph clearly shows that the pandemic went from being an urban issue to a rural issue in August of last year, and that the divergence only grew as time went on, until recently.

Now vaccines are widely available, but

public-health experts worry that rural residents will be more hesitant to get them, or outright resistant to the idea. They say the same sort of targeted communication that has been directed at communities of color needs to be designed to overcome rural reluctance.