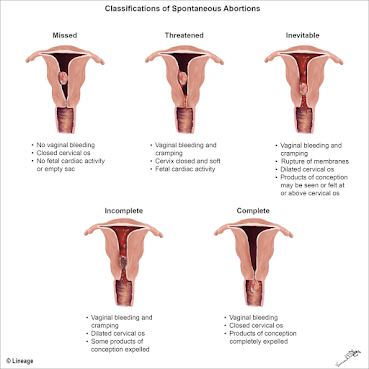

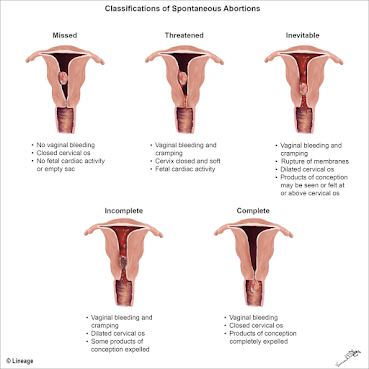

Uterus diagrams via Medbullets, an educational site; click to enlarge

—–

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

Federal officials have issued guidance in an attempt to clarify when health-care providers can perform an abortion in states that ban the procedure. It says that a physician must stabilize a patient who seeks treatment in a hospital emergency department, according to the federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act, passed in 1986.

“A physician’s professional and legal duty to provide stabilizing medical treatment to a patient who presents under EMTALA to the emergency department and is found to have an emergency medical condition preempts any directly conflicting state law or mandate that might otherwise prohibit or prevent such treatment,” says the

Department of Health and Human Services document.“If a physician believes that a pregnant patient presenting at an emergency department is experiencing an emergency medical condition as defined by EMTALA, and that abortion is the stabilizing treatment necessary to resolve that condition, the physician must provide that treatment. When a state law prohibits abortion and does not include an exception for the life of the pregnant person — or draws the exception more narrowly than EMTALA’s emergency-medical-condition definition — that state law is pre-empted.”

Kentucky’s abortion ban, triggered by the U.S. Supreme Court’s June 24 reversal of its

Roe v. Wade decision, has an exception for a threat to the woman’s life. It has been

blocked, at least temporarily, by a lawsuit.

Several Kentucky health-care providers have voiced concern about how the law doesn’t account for the complexities and complications that come with caring for women who need medical treatment for some miscarriages, Sarah Ladd

reports for the

The Courier Journal. Dr. Coy Flowers, vice chairman of Kentucky’s chapter of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, described a number of scenarios to the Louisville newspaper in which the law poses a challenge, such as when a woman is hemorrhaging heavily despite a fetal heartbeat showing up on an ultrasound.

Flowers told Ladd that while the law allows abortion when there is no longer a fetal heartbeat, he said a patient may suffer from a condition or event that creates an “inevitable abortion” scenario. “That means there is still a heartbeat, but the pregnant person has a condition, such as cervical weakness, that complicates the future of the pregnancy and the health — and life — of the patient,” Ladd explains.

“There are definitely scenarios, particularly in the middle to late second trimester, before what we consider as viability for fetuses, where there’s a lot of gray zone in our current trigger law that will put physicians at risk for liability, either monetarily or, particularly, a Class D felony,” Flowers told Ladd.

Ladd reports that in a press call on the day Roe v. Wade was overturned, ACOG President Dr. Iffath Abbasi Hoskins discussed the challenges of caring for women who are in the middle of an “incomplete” abortion, “where there is still a heartbeat and the woman is cramping . . . or bleeding or both.”

Now, when facing that situation, “Clinicians may be thinking that they have to wait,” she said. “They may be needing to get additional opinions, whether it’s a legal opinion, whether it’s another medical opinion.”

A

Kentucky ACOG statement that day voiced concern about the phrasing of the state’s

trigger law, saying it places Kentucky physicians and patients in jeopardy.

“The unclear language will, in all likelihood, force physicians to wait for a patient’s condition to deteriorate so severely that significant bodily harm or even death could occur,” the statement said. “Left to interpret ambiguous legal language in the middle of the night, Kentucky ACOG asserts that [the law] will deter physicians and hospital staff from providing life-saving interventions to patients whose health could worsen rapidly.”

Flowers said there could be confusion when deciding whether the life of the patient or the fetus must take legal priority, so physicians may pause in the middle of treating complex cases.

“I’ve been in a situation where a woman is wheeled in from the ER,” he told Ladd. “She’s been brought in in an ambulance. They rush her down to labor and delivery and you stand her up from the wheelchair to get into the bed. And you literally can hear … blood hitting the floor, bleeding that intensely. What if that happened? You stick an ultrasound on, and there’s a heartbeat. What do you do in that instance?”

At the 2022

Association of Health Care Journalists conference, Dr. Lisa Harris, an obstetrician-gynecologist at the

University of Michigan, also talked about the vagueness of abortion bans that make exceptions if the mother’s life is at risk, asking the question, “How much risk does someone need to take on to have an abortion count as life-saving?”

Harris continued: “For example, there are patients with cardiac disease who we will quote a 25 to 30 percent chance of dying if they continue the pregnancy and give birth. Is that enough of a risk of dying to have qualified, I guess, to use that word, to qualify for an abortion? Or does it need to be 50 percent or 100 percent? How are we to know this?”

In a

June 24 statement, Kentucky Attorney General Daniel Cameron said the state’s trigger law “has no application when a pregnant mother suffers a miscarriage. Nor does it prohibit medical treatment to help a mother in this circumstance.”

The HHS guidance addresses these issues and says that under EMTALA, physicians will be protected.

In a

letter to all health-care providers, HHS Secretary Xavier Becerra wrote, “The federal EMTALA statute protects your clinical judgment and the action that you take to provide stabilizing medical treatment to your pregnant patients, regardless of the restrictions in the state where you practice.”

Rachel Roubein

reports for

The Washington Post, “Doctors don’t need to wait for a condition to worsen or for the patient to be close to death before intervening, senior HHS officials told reporters yesterday. EMTALA also permits a provider to terminate a pregnancy when an emergency condition could seriously impair the patient’s health.”

HHS tried to make clear that it wasn’t writing new rules, saying near the top of the document: “This memorandum is being issued to remind hospitals of their existing obligation to comply with EMTALA and does not contain new policy.”

EMTALA requires that anyone who seeks care in an emergency department be stabilized, treated or transferred, regardless of their ability to pay. Violation could lead to the hospital being fined or losing its ability to get Medicare reimbursements for care, the guidance notes.