State, far behind on nursing-home inspections, focuses on responding to complaints, but that often takes too long

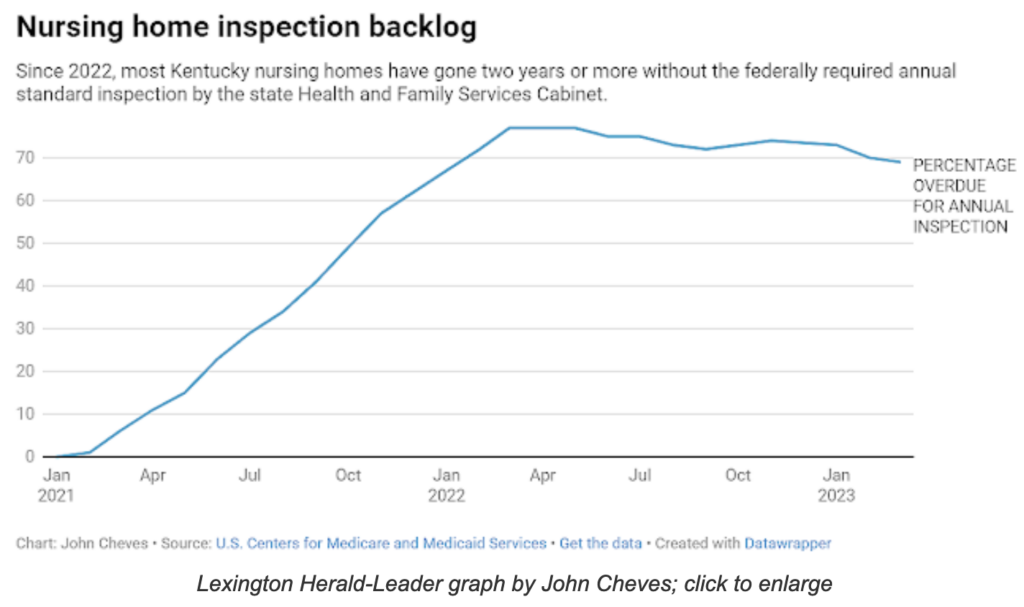

“As of June, 73 percent of Kentucky’s 277 nursing homes were listed as going more than two years without a so-called ‘annual’ inspection. It’s putting patients at risk,” the Lexington Herald-Leader reports. The national average is 11%.

The federal government, which “essentially funds the American nursing home industry,” requires annual, multi-day inspections “to catch problems early, before they get serious enough for residents to be hurt, sickened or killed,” John Cheves reports. “But because of a dangerous shortage of inspectors — the worst in the United States, according to one report — Kentucky hasn’t reliably performed standard surveys since the Covid-19 pandemic shut down the state in spring 2020.”

All this means “scant oversight at long-term care facilities, typically owned by for-profit corporate chains and where many thousands of vulnerable Kentuckians live every day,” Cheves writes. “The delays also erode the accuracy of Nursing Home Compare, the quality rating website” of the federal Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. “It’s based largely on state inspections. Families consult this website before picking a nursing home for their loved ones. They are referred to it by the state health cabinet and respected experts at AARP and the National Institute on Aging. Even before the current inspection backlog, Kentucky nursing homes had among the worst collective ratings in the country. In 2018, 43 percent were rated ‘below average’ or ‘much below average’ by CMS.”

Officials of the state Cabinet for Health and Family Services declined to be interviewed, and “also declined to answer most written questions the newspaper submitted over the next two months about Kentucky’s nursing home inspection backlog and the reasons for it,” the Herald-Leader reports. “In a brief statement, health cabinet spokeswoman Susan Dunlap said the cabinet acknowledges an inspection backlog has been created in Kentucky since the pandemic.

Dunlap said the state is working to address the backlog “by raising salaries for inspectors in an effort to boost hiring and retention,” Cheves writes, and is concentrating on “complaint surveys,” which are more focused visits “to look at a specific grievance about care that can be filed by residents, their families or others. . . . However, it can take two to three years for complaint surveys to work their way through their own separate backlog, said nurse Barbara Lear, a Kentucky nursing-home inspector who quit last summer. By the time inspectors finally arrive at a facility to investigate an old complaint, Lear said, residents involved in the case likely have died, and the employees no longer work there and might not want to speak to state officials about the allegations.”

Cheves reports, “State records show that last year, Kentucky inspectors received more than 1,700 of the most serious kinds of complaints, classified as ‘immediate jeopardy,’ up from about 1,000 in 2018. The percentage of complaint surveys started in the ‘federally required time frame’ — within a matter of days — fell from 85 percent to less than 4 percent during this period.”