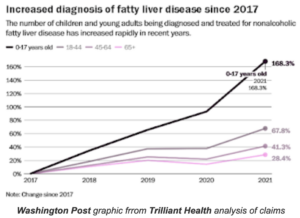

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease now common in children; experts at UK and elsewhere say causes include diet and lack of exercise

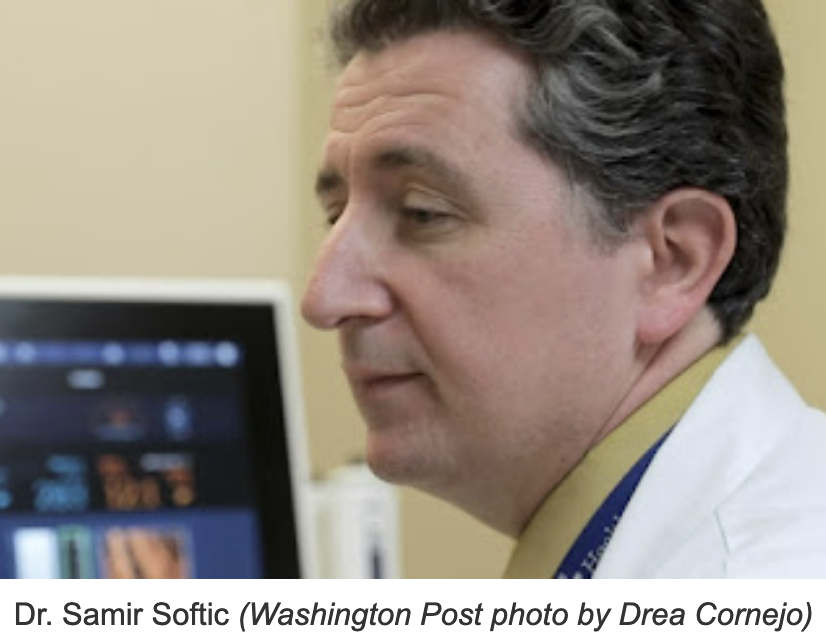

For uncertain reasons, nonalcoholic fatty liver disease has become more common in American children, especially in Kentucky, and “It’s the worst disease you’ve never heard of,” said Samir Softic, a pediatric gastroenterologist at the University of Kentucky Children’s Hospital, who specializes in the disease.

Softic is a main focus of a long story in The Washington Post about the disease, which is estimated to affect 5 to 10 percent of U.S. children, “making it about as common as asthma, Post reporter Ariana Eunjung Cha writes. A video with the story says Kentucky’s rate “is believed to be among the highest.”

Cha reports, “The crisis is especially acute in swatches of the Southeast, where rates of pediatric obesity are highest,” including Appalachian Kentucky. “But obesity is only part of the puzzle. Scientists have been surprised to find that not all kids with obesity have fatty liver, and not all kids who have fatty liver disease struggle with weight.”

Softic runs UK’s pediatric fatty liver clinic, which this spring was “often fully booked two to six months in advance,” Cha reports. The disease often has few symptoms until it becomes serious, at which point it can cause weakness, severe tiredness, weight loss, yellowing of the skin or eyes, spiderlike blood vessels on the skin and long-lasting itching,” says Johns Hopkins Medicine.

“For Softic, the fatty liver crisis is as much about policy as science. He has collected a stack of letters from insurers refusing to cover some patients’ treatment with a new generation of weight-loss drugs known as semaglutides, sold under brand names including Ozempic and Wegovy. The companies say the medications are not yet proven to help with fatty liver.

“While Softic believes that fundamental changes in how we eat and exercise are needed in the long term, he said lives could be saved in the short term if these drugs were widely and cheaply available. He’s lobbying state and federal regulators to help pay for the treatments — which can cost upwards of $1,300 a month — for patients younger than 18, who arguably have the most to gain because they have more of their lives ahead of them.

“While Softic believes that fundamental changes in how we eat and exercise are needed in the long term, he said lives could be saved in the short term if these drugs were widely and cheaply available. He’s lobbying state and federal regulators to help pay for the treatments — which can cost upwards of $1,300 a month — for patients younger than 18, who arguably have the most to gain because they have more of their lives ahead of them.

“Liver transplants in children diagnosed with fatty liver disease remain rare, but Softic recently referred a 6-year-old for a transplant evaluation. There has been a clear rise in transplants for fatty liver in people in their 20s and 30s, meaning if he can’t help his pediatric patients now, they may soon face a transplant.”

Softic told Cha the disease “goes unnoticed and unrecognized, and over time it catches up. For a good number of these young transplant patients, the disease process started in childhood,” he said. “On so many levels, we are not prepared to deal with this disease in children.”

A seven-minute video with the story includes the case of Sydney Woods, a Kentucky 15-year-old with fatty liver disease who improved her liver function by “cutting out soda and making other changes to her diet . . . but it’s not as easy for most families to buy less procesed food.” That’s especially true in rural areas, said her mother, Angela Woods, a physician’s assistant.

Softic says in the video, “Eating healthy requires time, it requires money, and not everyone has those resources.”

Cha reports, “Many doctors believe that our modern lifestyle — diet, the increase in sedentary activities related to technology and environmental exposures — is to blame. One of the liver’s jobs is to filter toxins, and when something in the body is out of balance, the organ can become damaged and fail. Some pediatric experts theorize there’s a mismatch between our genetics and the highly processed and sugary foods that have come to dominate childhood diets,” including some types of infant formula. The video says 67% of children’s diets consist of ultra-processed foods.

“It’s a major problem, and it’s been exacerbated by diet and inactivity,” Simon Fisher, director of UK’s Barnstable Brown Diabetes Center, says in the video.

Cha reports, “The escalation of pediatric fatty liver cases has unfolded in tandem with the presence among the young of other conditions once viewed as almost exclusively adult diseases: high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, even gallstones.”