There is evidence that social media hurt teens’ mental health, but the evidence is not definitive; what restrictions are reasonable?

By Katelyn Jetelina and Jacqueline Nesi

Your Local Epidemiologist

Strong bipartisan statements came out of a congressional hearing yesterday about the harms of social media use among children and teens. Parents of kids harmed by social media showed up in immense force.

“You have blood on your hands.”— Sen. Lindsey Graham to five social media CEOs.

“I’m sorry for everything you have all been through.”— Mark Zuckerberg to parents in the audience.

Is social media dangerous for children and teens? And, if so, what are our options?

Here is the nuanced public health data that (hopefully) congressmen/women are using to (hopefully) make meaningful and needed change. But, as we know by now, policy isn’t always based on science.

This was published eight months ago, and some things have changed since. As a parent, I still root for Option #4.

Protecting youth from the potential negative mental-health effects of social media is front and center in the mass media, in conversations around dinner tables, and in federal- and state-level bills.

According to diagnostic measures (structured interviews by a trained professional), depression has increased 7.7% in U.S. teens—and 12% among girls—between 2009 and 2019.

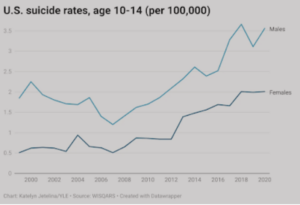

According to U.S. death certificates, suicide rates among youth ages 10-14 increased 139% for girls and 70% for boys since 2012. However, this is a bit difficult to interpret given low the rates to begin with for girls.

According to U.S. death certificates, suicide rates among youth ages 10-14 increased 139% for girls and 70% for boys since 2012. However, this is a bit difficult to interpret given low the rates to begin with for girls.

Is this rise due to social media? Teens use social media. A lot. Almost one in five teens use YouTube “almost constantly.” Nearly half of teens use TikTok (48%) and Snapchat (44%) several times per day. And the total hours of use have increased in recent years among teens.

But using social media doesn’t necessarily equate to mental-health problems. Correlation doesn’t always equal causation. And, to make things more complicated, there are harms and benefits of social media.

Correlational studies ask teens how much time they’re spending on social media, and ask them about mental health. In general, these point to weak but statistically relevant correlations between social media use and lower teen well-being.

In terms of causal evidence, we have a couple of studies:

Some studies randomly assigned people (both adults and teens) to stop using social media (and others not to stop) and then evaluated their well-being. The results of these studies are mixed. Variability seems to depend on the details of the design: How long did they stop using social media? Did they “detox” completely or just reduce the time spent? What are they using social media for?

Other studies have taken advantage of circumstances that naturally occurred in the world to mimic an experimental design. One study looked at when Facebook was introduced on different college campuses (which varied randomly) and found that after Facebook showed up, rates of mental-health concerns increased. A few others (like this and this) look at the introduction of high-speed Internet in different areas and found associations with poorer mental health after its introduction, but these studies do not address social media specifically.

What is clear is that we need more research with more rigorous designs.

- Helping them stay connected with friends

- Meeting like-minded peers

- Exploring their interests

- Learning

- Discovery

These benefits can be especially important for those who may be socially vulnerable in their offline lives, such as LGBTQ+ youth.

- Rising income inequality

- Wars

- Violence and access to firearms (suicides)

- Global financial crisis

- Racial inequality

- Academic and social pressures

- Political views on current events

- Climate change

- The opioid epidemic

- Unhelpful narratives around mental health

Option 1: Do nothing until research is “settled” on the issue before taking legislative action. Unfortunately, this may require a “burden of proof” that is rarely, if ever, established in psychology research. In this case, some evidence of harm, even if imperfect, may need to be enough to drive change.

Option 2: Put it on the parents. Parents certainly play a hugely important role in teens’ relationships with social media. Evidence supports parents’ active involvement in kids’ digital lives through ongoing conversations, reasonable limits, and appropriate monitoring. But can (and should) they manage it alone? If large-scale policy changes create safer social media platforms, individual disadvantages are minimized.

Option 3: Ban it among minors. Some states, such as Arkansas and Utah, have passed bills that limit social media use. In one case (Florida), it’s banned among kids under 16.

Option 4: Put reasonable protections in place. Social media is probably more like cars than drugs. We want protections in place (seatbelts, airbags, drivers’ ed), but an outright ban may go too far. Some options include: raising the minimum age from 13 to 15 or 16; requiring age verification of some kind; limiting recommendations of harmful or problematic content; limiting overall time spent (such as via forced “breaks” or overall time limits); and limiting targeted advertising.