State Senate restores most Medicaid cuts made in the House

The state Senate has largely eliminated cuts to Medicaid that were proposed in the House budget. A top state official had warned the House plan would create a hole next year in the federal-state health plan that covers 1.5 million low-income Kentuckians, a third of the state’s population.

“We are pleased that the Senate’s proposed budget restores funding to Medicaid so patients can continue to access the necessary health care services they’re accustomed to,” said a statement from the Cabinet for Health Services, which manages the $15 billion a year federal-state program.

Cabinet Secretary Eric Friedlander appeared before the Senate Appropriations and Revenue Committee last month, along with John Hicks, budget director for Democrat Gov. Andy Beshear, asking the Republican-majority Senate to consider restoring the funds the House cut for the fiscal year that begins July 1.

“This creates a hole in the Medicaid budget for Fiscal Year ’25,” Hicks told the committee.

Advocates worry the House plan could force cutbacks in Medicaid services through more than $900 million in cuts to the amount sought by Beshear.

Republicans generally have expressed support for the Medicaid program, which pumps money into hospitals, clinics, pharmacies and other medical services throughout the state—with 70% to 80% of the funding provided by the federal government. But some have expressed concern that it has grown so large.

The Kentucky Center for Economic Policy told the Lantern last month that overall, the House plan cut about $139 million in state funds Beshear sought for Medicaid in fiscal 2025, which would cause the state to forfeit another $783 in federal matching money, for a total of around $922 million.

The Senate moved its budget bills through committee and to a final floor vote on Wednesday. Dustin Pugel, policy director for the center, said Thursday it appeared the Senate had restored most of the funds but made some cuts including a reduction in “waiver programs” for people with disabilities.

The House plan included about $200 million — about $143 million of that in federal funds — for 2,550 new slots in Medicaid “waiver” programs such as “Michelle P.” that provide housing, therapy or other supports for people with disabilities.

Thousands of people are on waiting lists for such services, which generally have been increased by only 50 or so each year.

The Senate version reduces the number of slots over the next two budget years to 1,925.

The Senate did not fund the proposed “mobile crisis units,” which were also left out of the House budget. They would provide an alternative to police intervention when someone is experiencing a mental-health crisis.

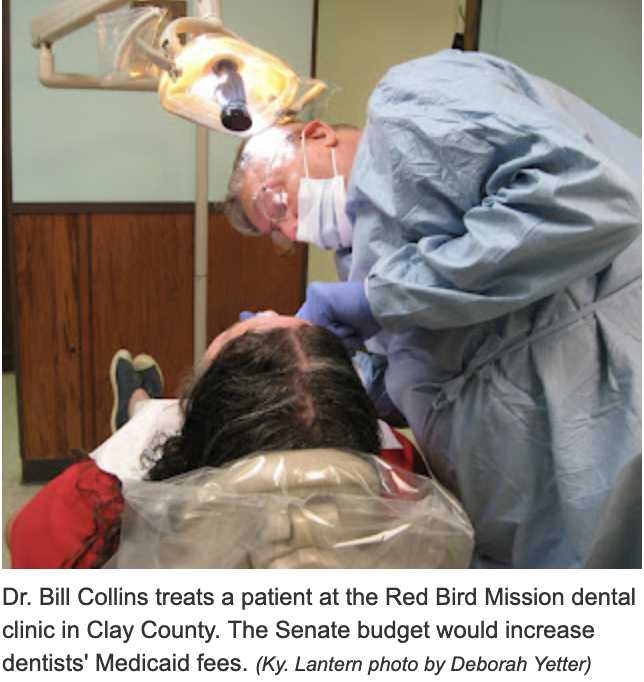

But the Senate did include an increase in Medicaid payments for dental services, which oral-health advocates say is urgently needed to attract more dentists to the program in a state with high rates of dental disease.

Overall, Pugel said, the Senate plan is “good news for the Medicaid budget.”

However, the budget process is far from over. The House will consider the Senate changes, and if it disagrees, as is usually the case, the budget will be decided by a House-Senate conference committee.