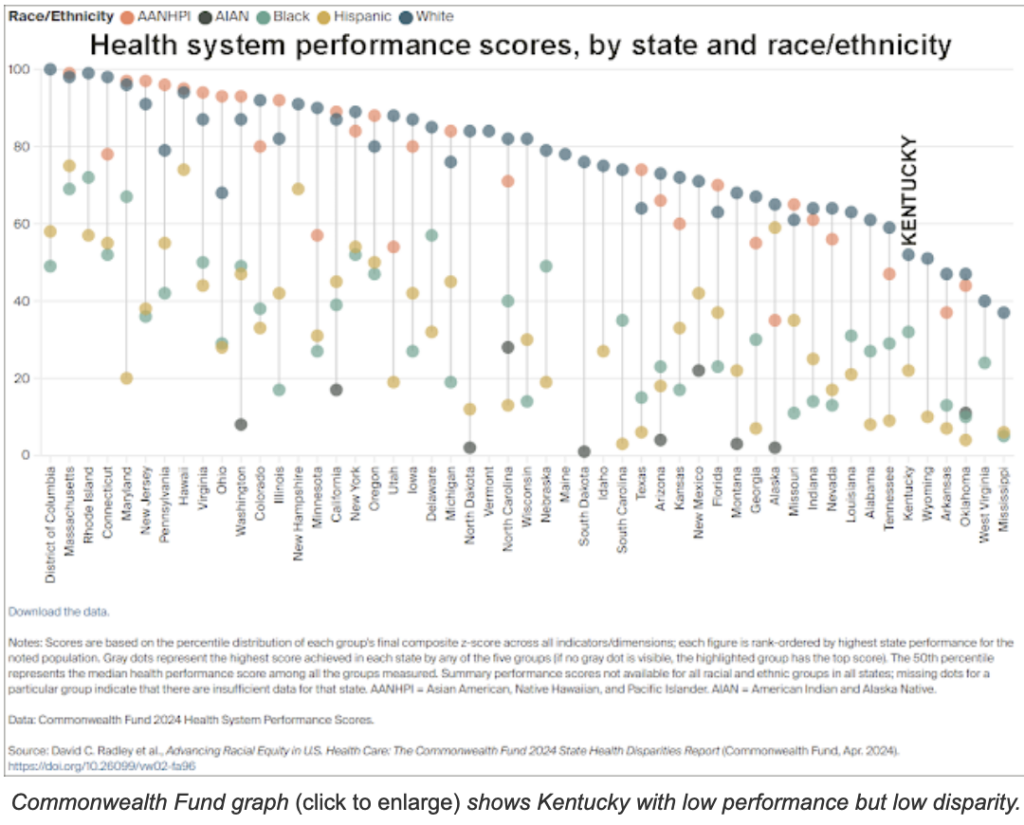

National report on health-system performance ranks Kentucky low, but disparities among its racial and ethnic groups are also low

Kentucky Health News

A new report from The Commonwealth Fund, a New York-based foundation, shows racial and ethnic disparities persist in health-care access, quality, and outcomes in Kentucky and across the nation.

“In every state, we find wide disparities in health and health-care experiences for people of different racial and ethnic backgrounds,” David Radley, a senior scientist for The Commonwealth Fund, said during an online press conference. “And that health system performance is markedly worse for people of color when compared to the experience of white people.”

The Commonwealth Fund, which says it aims to promote a high-performing health-care system, issued its 2024 State Health Disparities Report on April 18.

The report used 25 measures to determine health-system performance, evaluating states on health-care access, quality, use of services, and health outcomes for people of different races and ethnicities in each state. It then gave a health-system performance “score” for each racial and ethnic group.

In Kentucky, white people had the highest score, in the 52nd percentile among all population groups nationally, making them about average. Hispanic Kentuckians had the state’s lowest health-system performance, scoring in the 22nd percentile. Black Kentuckians scored in the 32nd percentile.

Despite those health disparities, when compared to other states in the Southeast, Kentucky has smaller disparities among its racial and ethnic groups. That’s largely because Kentucky’s whites rank lower than whites in all states except Wyoming, Arkansas, Oklahoma, West Virginia and bottom-ranking Mississippi.

The report says health disparities are influenced by a number of factors, including a lack of affordable, quality health-care options, and whether a person has health insurance or a primary-care provider. It is also influenced by social determinants, such as whether a person lives in an area of high crime, has access to transportation or lives in poverty. And it is also influenced by whether they have to deal with racism and discrimination in healthcare settings.

“Where a person lives matters, and this is especially true for people of color,” Radley said. “We also see big differences in people’s abilities to access care. Not only do uninsured rates vary from state to state, we also find big differences within states where we see large coverage gaps between people from different racial and ethnic groups.”

The researchers said their work points out that only looking at how a state performs overall can mask the “profound inequities” that many people experience.

Dr. Laurie Zephyrin, senior vice president for advancing health equity at The Commonwealth Fund, said improving health equity will require policy action and health system action.

“One key area is around insurance coverage and affordability. Insurance coverage is a key part of this. It is the floor in terms of ensuring that everyone has access to health care. And it is really critical,” Zephyrin said. “When we look at the data about 25 million people in the United States are still uninsured, and they’re disproportionately people of color. And even for people who are insured, about a quarter of working-age adults are underinsured.”

Kentucky made a big policy decision to increase access when it expanded Medicaid in 2014 to people with incomes up to 138% of the federal poverty line under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act.

Nevertheless, 28% of Hispanic adults in Kentucky have no health coverage, compared to 8% of Black adults and 6% of white adults. Having no insurance, or having plans that require high out-of-pocket costs relative to a person’s income, cause people to not seek care when they need it.

Two of the nine health-outcome measures that the researchers looked at were premature, treatable and preventable deaths before the age of 75.

In Kentucky, Blacks had the highest death rate for treatable conditions,171 per 100,000 people. This was followed by Whites with 119 deaths per 100,000, Hispanics with 57 per 100,000, and Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander (AANHPI), with 58 per 100,000.

Black Kentuckians also led the state for deaths before the age of 75 from preventable causes per 100,000 people, with 402 deaths per 100,000. This was followed by whites, at 328; Hispanics, 173; American Indian and Alaska Native, 111; and AANHPI, 104.

“Premature preventable mortality rates are higher for both Black and White residents in several Southern and South Central states — Arkansas, Mississippi, Louisiana, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Missouri — compared to most other parts of the country,” says the report.

Compared to other states, Kentucky’s health system performance for Black people was better than average, ranking 18th of the 39 states where the calculation of a Black rate was statistically reliable.

Kentucky’s health-system performance was ranked worse than average for Hispanics, ranking 29th of 47 states.

And with a ranking of 46th of 51 states, Kentucky’s health system performance for white people was considered among the worst compared to other states.

The researchers said the hope is that policymakers, health system leaders and community stakeholders will use this information to inform future policy that will ensure a more equitable health care system in the future.

The report offered four policy options toward this goal, with detailed suggestions for each of them on how to accomplish them. The policy options would ensure universal, affordable and equitable health coverage; strengthen primary care and improving the delivery of services; reduce inequitable administrative burdens affecting patients and providers; and invest in social services.

“This analysis will give policymakers and health-care leaders a critical roadmap to enact targeted policies and make the key investments to eliminate disparities and achieve health equity,” said Dr. Joseph Betancourt, president of The Commonwealth Fund. “Just as deliberate choices have been made that have put us in the situation, we can now be deliberate about promoting high-quality equitable health care for all. This undoubtedly will create healthier, more resilient communities that would ultimately benefit the entire nation.”