Hard choices face Kentucky Republican tasked with recommending Medicaid cuts

By Jamie Lucke, Sarah Ladd and McKenna Horsley

Kentucky Lantern

As U.S. Rep. Brett Guthrie prepares to lead a debate on the future of Medicaid, his home state of Kentucky has more at stake than most.

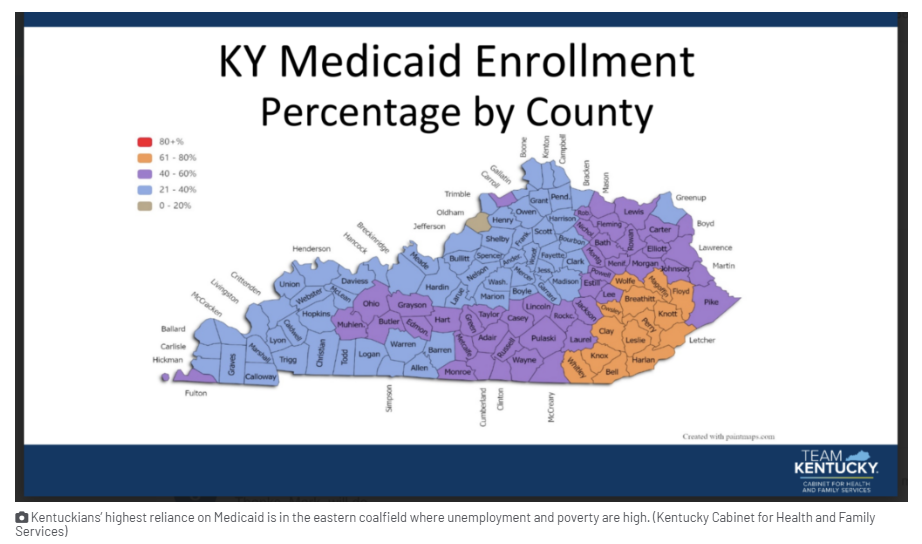

Guthrie, R-Bowling Green, is chairman of a House committee that on Tuesday is set to start proposing $880 billion in federal budget savings over the next 10 years. Guthrie’s assignment will be impossible, experts say, without cutting the federal-state program that pays for almost 1 in 3 Kentuckians’ health care and has become an underpinning of the economy.

“Medicaid has become important to local economies throughout the state and a key pathway to health care for many Kentuckians,” says the Kentucky Chamber of Commerce in a statement last week that also mentions the Chamber’s “long-voiced concerns about the impact of rising Medicaid costs on Kentucky’s finances.”

“Efforts to control Medicaid spending will be necessary,” says the pro-business group whose top recent priority has been continuing to lower Kentucky’s income tax. “Policymakers, however, will need to take a balanced approach with input from key stakeholders.”

Guthrie, a West Point graduate and former state legislator, is not publicly discussing specifics ahead of the markup, a spokesperson for the committee said Friday.

“Chairman Guthrie and Energy and Commerce Republicans are ready to strengthen, secure, and sustain Medicaid for generations to come and for the Americans the program was intended to serve,” said Matt VanHyfte, the director of communications for the House Energy and Commerce Committee.

Sounding a common GOP theme, he said Medicaid was intended “to assist the ‘traditional population,’ which are expectant mothers, children, low-income seniors and people with disabilities.”

Medicaid was expanded beyond that traditional role in 2010 when Congress — with no Republican votes — enacted the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, a law that became known as Obamacare.

By then, the number of uninsured had topped 46 million, nearing 1 in 5 Americans; medical bills were increasingly pushing sick people into bankruptcy as hospitals shifted costs onto the dwindling share of insured patients.

‘Salvation for small rural hospitals’

Kentucky, a poor state with lots of sick people, has aggressively embraced the new option, and that has “changed the dynamics considerably,” says Mark Birdwhistell, an expert on Medicaid and the University of Kentucky’s senior vice president for health and public policy.

The Medicaid expansion has been “a great benefit to the health care delivery system at the University of Kentucky and all over Kentucky, particularly Southeastern Kentucky,” Birdwhistell told the Lantern. “It’s been a salvation for small rural hospitals in Eastern Kentucky and good for health outcomes as well,” Birdwhistell said.

The rate of uninsured Kentuckians fell from 14.4% in 2013 to 6.1% in 2015, the year after the Medicaid expansion took effect. In 2023, 5.6% of Kentuckians were uninsured compared to 8% of the U.S. population.

Birdwhistell has been spending a lot of time in Washington sharing his knowledge with Kentucky’s congressional delegation and with the staff of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, which oversees Medicaid, Medicare and the Children’s Health Insurance Program.

In an interview with the Lantern, Birdwhistell discussed some of the Medicaid proposals the Republicans who control Congress are considering as they look for savings to pay for continuing tax cuts enacted in 2017 during President Donald Trump’s first term.

Lowering federal share would be $1.4 billion hit to Kentucky

The proposal that would be the “most problematic” for Kentucky, Birdwhistell said, is one to lower the matching funds the federal government pays for the Medicaid expansion. After paying 100% of the expansion for a few years, the federal match was lowered to 90%, leaving states to pick up 10% of the expansion cost.

By contrast, the federal government picks up 71% of the cost of insuring Kentucky’s traditional Medicaid population. (Kentucky receives a higher federal match than most states because it’s based on a state’s per capita income, and Kentucky’s is comparatively low.) Of Kentucky’s $19 billion Medicaid budget, almost $15 billion comes from the federal government and about $4 billion from state sources.

If Congress decides to lower the expansion match to the lower share for the rest of the program, Kentucky would have to provide an additional $1.4 billion to continue covering the almost 500,000 people in the expansion, according to an estimate by the Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services.

“It would be difficult for the General Assembly to come up with that amount of money,” said Birdwhistell.

Birdwhistell said he understands why some members of Congress question the more generous federal match for the Medicaid expansion, but said, “In Kentucky, in my opinion, the benefits outweigh the downside.”

Block-granting Medicaid would threaten traditional population

Another option being floated would impose per capita caps on federal funding for Medicaid, in essence a block grant based on the size of the covered population, which Birdwhistell said would likely cause negative impacts for the traditional Medicaid population, especially the disabled and frail elderly, new mothers and babies who need neonatal intensive care.

Under a cap, some patients could be denied care if their costs exceeded a designated amount, he said, making it difficult to administer and producing “negative policy outcomes.”

If a per capita cap is the Republicans’ chosen alternative, Birdwhistell said it would be better to apply it to the expansion population, who are healthier, younger and cheaper to insure.

Among the almost one million Kentuckians covered by traditional Medicaid is Caden Plemons, 19, of Bowling Green. He has Down Syndrome and autism and is “primarily nonverbal,” says his mother Rheanna Plemons, who worries lawmakers will subject Medicaid to “broad, sweeping cuts, without doing any research to ensure that it’s not decreasing the standard of care for individuals with intellectual disabilities.”

Caden also receives services through Kentucky Medicaid’s Michell P. waiver, which helps people who have intellectual disabilities live more independently. Caden’s community living supports include staff to help him with daily tasks like dressing, going to appointments and getting out to enjoy go-karts and other activities.

“He’s thriving in the community because of the services that we have received over the last 19 years,” Plemons said.

Caden’s waiver also covers respite care so Plemons and her husband can “take a break every now and then.”

“Sometimes people don’t realize: if you have a child who has a severe disability, such as my child, that’s 24 hours a day care, seven days a week,” Plemons said. “I work. My husband works full time. So if we want to take a break, even to go out to have dinner with just the two of us, then somebody’s got to be there with Caden, even though he’s 19 years old.”

Work requirement expands bureaucracy

Another option under consideration for trimming Medicaid costs is a work requirement. Birdwhistell estimates that more than half of able-bodied Kentuckians covered by Medicaid — the working poor — already hold low-wage jobs. The income limit for most working-age adults to qualify for Medicaid is 138% of the federal poverty level. That works out to $44,367 a year for a family of four, which “in some areas of the state is quite a few people,” said Birdwhistell.

Enforcing a Medicaid work requirement would require funding an expanded bureaucracy to keep up with new reporting demands and ensure compliance, Birdwhistell said.

The Republican-dominated Kentucky legislature this year enacted a Medicaid work requirement that will be up to Democratic Gov. Andy Beshear’s administration to bring online.

Critics view work requirements as a smokescreen for using red tape to push people off the Medicaid rolls.

Megan Rorex, a licensed clinical social worker and therapist in Bowling Green, predicts new reporting demands would snag her Medicaid-covered clients. Many of them work multiple part-time jobs, often in the restaurant industry, and would lack the time or bandwidth to keep up with an additional layer of paperwork in a program that she considers already overcomplicated. “Any bureaucratic policy that’s unnecessary is a problem to navigate if you’re already working multiple jobs. It adds another layer of stigma and stress,” she said.

Provider taxes and state-directed payments

Some Republicans, including Russell Vought, director of the Office of Management and Budget and an author of the Heritage Foundation’s Project 2025 agenda for the second Trump administration, want to limit states’ use of levies on health care providers — called provider taxes — to leverage higher Medicaid funding from the federal government.

Kentucky levies a number of provider taxes that bring additional federal Medicaid funds into the state and pay for state-directed payments that increase hospitals’ Medicaid compensation to levels that, on average, are what private insurers would pay for the same services. Directed payments bring $5.5 billion a year to Kentucky providers, most of it from the federal government.

So far, congressional discussion has focused on capping provider taxes at 5% of hospital patient revenue, which would not affect Kentucky because provider tax rates here are below 5%, Birdwhistell said.

Kentucky is using these payments to incentivize quality improvements, such as more frequent well-child visits and screenings for disease. Hospitals must meet the quality objectives to qualify for the extra funding, which Birdwhistell says has been “extremely successful” in transforming UK Healthcare into a “value-based organization.” He said he’s advising federal officials that Kentucky’s use of provider taxes to improve quality is a model worth replicating in other states.

Slow return on investment

A complaint voiced by some Republican state lawmakers during this year’s session in Frankfort is that Medicaid spending increases each year — almost $2.6 billion budgeted from Kentucky’s General Fund in fiscal year 2025 — without producing improvements in health outcomes.

Birdwhistell said it takes a long time to realize the return on investment in health care. “These are generational issues,” he said. “It takes a person’s lifetime before you can say what the savings were.”

And Kentuckians are inching out of the nation’s basement on some health indicators.

In 2024, Kentucky advanced to 41st among the 50 states — up from 45th in 2016-2021 — in America’s Health Rankings, an annual study by the United Healthcare Foundation based on a variety of health, behavioral and socioeconomic metrics.

On the upside,

- The rate of colorectal screenings in Kentucky rose from 20th nationally in 2022 to 10th in 2024.

- Kentucky’s obesity rank improved from 48th in 2022 to 40th in 2023.

- And Kentucky’s drug-related deaths declined from 47th highest among the states in 2022 to 45th in 2024. Medicaid has been the main source of funds for bringing down fatal overdoses and treating the opioid epidemic.

- Kentucky ranked 16th nationally in the availability of primary care providers last year, down from 11th in 2023.

The study also identifies plenty of room for improvement. Kentucky ranked 49th for adults with multiple chronic conditions in 2023 and 45th for the percentage of households experiencing food insecurity in 2024.

The politics

While Guthrie’s role in potential Medicaid cuts is not expected to hurt his chances next year for reelection to a 10th term, Republicans representing swing districts in Congress could face a voter backlash, and some are refusing to vote for Medicaid rollbacks pushed by more conservative colleagues. Republicans’ narrow margin in the House means even a few defectors could doom budget provisions, while a few midterm defeats next year could give Democrats control of the chamber.

Candidate Trump promised to protect Medicaid, and the White House reiterated that promise in March, but Trump is also urging Congress to enact the House budget blueprint that he calls the “big beautiful bill” — goals that appear to be in conflict.

Guthrie will be a “key player,” says Birdwhistell, as his committee works this week to move the House budget proposal closer to a vote by the full House.

Tres Watson, a former spokesperson for the Republican Party of Kentucky, echoed the talking point that Guthrie is working to return Medicaid to its original, pre-Affordable Care Act role, “reining in what many Republicans view as out of control entitlement spending, getting away from what was originally intended to be … a trampoline, not a mattress,” Watson said.

Kentucky’s top Democrat, Gov. Andy Beshear, has joined Democratic governors in calling on Congress to protect Medicaid funding. In a Democratic Governors Association press call last week, Beshear, the group’s vice chair, told reporters that “gutting Medicaid would impact families in a substantial way.” He said half of Kentucky children and 70% of long-term care costs in Kentucky are covered by Medicaid.

“Massive cuts to Medicaid is an attack on rural America, and if they do it, these Republican representatives and senators are saying they don’t believe that the people of rural America deserve the same access to health care as those in urban America,” Beshear said. “Certainly it would devastate my state, but it would devastate so many of our communities in every single state across the United States.”

‘The only system in the world like it’

The fate of rural hospitals is bound to weigh on Republicans who were sent to Washington from red states. Even if hospitals are not forced to close, Medicaid cuts could force hospitals to lose services, says Ben Chandler, who retired last year as president and CEO of the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky. Before that, he was Kentucky’s attorney general and auditor and represented the state’s 6th Congressional District from 2004 to 2013.

For Chandler, the debate highlights the need for broad reform that would move the U.S. away from relying on employers to provide health coverage through a for-profit insurance industry that wields enormous influence on Capitol Hill.

“It’s ridiculous we don’t have Medicare for all or whatever you want to call it,” said Chandler who voted against the Affordable Care Act in 2010 because a proposal for a government-run “public option” health insurance plan was removed from the bill as a concession to the insurance industry and its supporters.

Chandler called the U.S. system “accidental,” born of World War II wage caps that inspired employers to compete for workers by offering a hospitalization benefit.

The U.S. spends twice as much on health care per capita as other large, wealthy nations, while U.S. health outcomes are far worse than those in other nations.

Says Chandler, “It’s the only system in the world like it.”