New oral-health plan includes expanded role for hygienists, soft-drink tax to fund loans to get more dentists in under-served areas

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

Kentucky’s new plan for oral health calls for the state to expand the role of public-health hygienists, find other ways to expand the dental workforce in under-served areas, and raise dentists’ Medicaid fees. And to pay for part of the plan, it calls for a tax on soft drinks that cause tooth decay.

The challenge is that all of these suggestions require action by the Kentucky General Assembly.

The Strategic Plan on Oral Health was assembled after more than 120 stakeholders and oral-health advocates attended a two-day summit and small-group meetings to set the state’s oral health priorities. The last plan was released in 2006.

One key strategy would require lawmakers to expand the scope of practice for public-health dental hygienists in Kentucky.

Current law says public-health hygienists have to be employed or contracted by a public health department. The state has only 18 hygenists, working in 10 programs in 33 counties. They largely provide preventive care, patient assessment and referrals for under-served children in public schools.

The plan calls for the hygienists to be allowed to practice in more settings, such as nursing homes, group homes, juvenile justice facilities and some correctional facilities, and to let them apply silver diamine fluoride, a liquid that stops tooth decay and reduces pain until the patient can see a dentist.

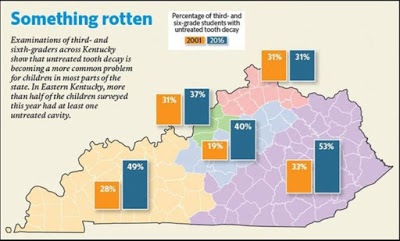

The proposals are aimed at the widespread tooth decay in Kentucky children. A 2016 study by Delta Dental and Kentucky Youth Advocatesfound that two out of five Kentucky third and sixth graders have untreated cavities, and the problem is “significantly greater” in Appalachian Kentucky, where more than half of the children in the study had untreated cavities.

The plan also calls for allowing public-health hygienists to use tele-dentistry, which would allow them to see more patients in a more timely fashion.

“To expand the ‘scope of practice’ would allow public-health hygienists to assist in arresting disease and pain, while still focusing on getting them care by a dentist,” Julie Watts McKee, dental director for the state Department of Public Health, said in an email. “It improves access. And access improves health.”

Expanding the scope of practice for public-health hygienists was widely supported at the two oral health summits, but a survey before the events found that only 24 percent of the dentists in the poll supported expanding hygenists’ scope of practice, compared to 97 percent of hygienists. The poll surveyed 64 dentists and 67 hygenists among 474 people defined as interested in Kentucky’s oral health.

Another goal of the plan is to find ways to entice dentists to practice in Kentucky’s under-served areas, such as tax incentives, educational debt reimbursement and increasing Medicaid fees.

The plan stresses that better data collection is needed to support its goals. It says one dentist who is listed as taking Medicaid patients made only 14 Medicaid claims in one year, indicating that the need for access to dental care is greater than is being reported. “Data drives good policy,” McKee said at an October health committee meeting about the report.

Kentucky offers the Kentucky State Loan Repayment Program, which is funded though the National Health Service Corps and administered by the Kentucky Office of Rural Health. However, such loans are offered to only a dozen or so Kentuckians each year, and are available to not only dentists, but to other health-care providers willing to work two years at an “eligible site.”

The strategic plan calls for a state-funded repayment program for new dentists who agree to practice in limited-access or under-served areas, a budget decision for the General Assembly. The report points out that Kentucky likely has enough dentists overall, but instead has a “maldistribution” problem: not enough of them in too many places.

Richard Whitehouse, executive director of the Kentucky Dental Association, said in an email that KDA supports the debt-relief proposal, and has lobbied the federal government for such funding, but “This is a difficult sell at this time.”

Whitehouse wrote, “A properly run program of debt forgiveness or loan repayment would greatly expand access to care. I have heard of studies suggesting that if a provider establishes a practice for at least three years, they are likely to remain. So, this investment could have a lasting effect on improving access to care and oral health outcomes.”

The plan notes that Kentucky Medicaid’s low reimbursement for dental services is a huge challenge in getting dentist to work in under-served areas. The plan calls for the state to compare current Medicaid fees to the regional “usual and customary rates” and adjust them accordingly, a suggestion made by a Medicaid official at the summit.

Whitehouse said Medicaid usually pays 30 to 40 percent of what is considered a “usual and customary rate.” He added that a practice can break even if its Medicaid patient base is below 25 percent of its total, but above that, “the dentist is actually losing money and the practice begins to suffer.” He added, “This accounts for why it is difficult to encourage new dentists with $250,000 of student debt to start a practice in areas of greatest need.”

The report says slightly more than a third of dentists in Kentucky do not accept Medicaid, and one in five report that fewer than a third of their patients are covered by Medicaid. Ten Kentucky counties, mostly in Western Kentucky, have no dentist who cares for Medicaid patients.

To help fund the loan-repayment program, the plan calls for the state to implement a soft-drink tax. This idea was referred to the nongovernmental Kentucky Oral Health Coalition, which said in an email that its members would discuss the proposal and determine if it’s a priority they want to tackle.

Whitehouse said KDA is in full support of a soft-drink tax, and has found a lot of stakeholder interest in it, but no support in Frankfort for it.

“Because of the correlation between soda and oral decay, this seems an appropriate response in order to improving oral health in Kentucky,” he said. “Earmarking the revenue from such a tax to loan repayment or increasing Medicaid reimbursement would also expand access to care. We believe, if we can get off the bottom of national rankings relating to oral health, this will also have an economic benefit in terms of our workforce and tax base.”

The report also calls for the Kentucky Oral Health Coalition to lead the effort in finding ways to improve the oral health literacy of non-dental health professionals, the general population and especially policy makers.