Improving Kentuckians’ health will require education, fighting poverty; poor and less educated have poorer health, study shows

Kentucky Health News

Increased access to insurance is just one part of the equation to improve the health of Kentuckians, improving poverty and increasing education levels are disparities that must also be addressed if Kentucky ever hopes to improve the health of its citizens.

“We believe that health disparities can be eliminated, and that they must be eliminated,” say the authors of a recently released report, Money Matters: Health Disparities in the Commonwealth – a Report on Socioeconomic status and health in Kentucky. “The first step towards eliminating health disparities is to understand and monitor where they exist.”

The report was released by the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky and the University of Kentucky College of Public Health.

Using 2011-12 data from the Kentucky Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (the most recent data available), this report looked at the relationship between health, income and education and found that poverty and lower education levels are consistently associated with poorer health.

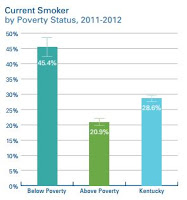

The data show that people who live in poverty and those with less education are more likely to be smokers. Smoking is a known cause of cancer, heart disease, stroke and other chronic conditions.

In 2011-13, the smoking rate in Kentucky was 28.6 percent, with almost one in three adults smoking. Of this group, almost half of the smokers (45.4 percent) were below poverty, while 20.9 percent were above poverty; and more than four in 10 (44.6 percent) had less than a high school education and about one in 10 (11.9 percent) were college graduates.

Obesity, which contributes to heart disease, stroke, type 2 diabetes and cancer, was also found to be more prevalent among the poor and uneducated.

The report found that 30.8 percent of Kentuckians were obese. Of this group, 38 percent lived below poverty and 30.9 percent lived above poverty; and 33.6 percent of those with less than a high school degree were obese, compared to 25.5 percent of college graduates.

Two-thirds of Kentuckians were considered overweight in the survey, and this was consistent across socioeconomic and education groups.

Poor, less educated Kentuckians in the survey also reported that they were less physically active and that they had increased activity limitations than those who lived above poverty and with more education.

Another health indicator among poor, less educated Kentuckians was that they were more likely to describe their health as fair or poor. Of the 23.1 percent of Kentuckians who described their health as fair or poor, 44.6 percent were below poverty and 17.6 percent were above poverty; and 45.2 percent of them had less than a high school education, while 9.1 percent of them were college graduates.

This finding was also true for people reporting poor physical health and poor mental health.

Of the 16.8 percent of Kentuckians who said they had poor physical health, 36.5 percent lived below poverty and 12.3 percent lived above poverty; and 30.8 percent had less than a high school education, while 7.4 percent were college graduates.

Of the 15.9 percent of Kentuckians who said they had poor mental health, 33.9 percent lived below poverty and 11.1 percent lived above poverty; and 28.2 percent had less than a high school degree, while 7.8 percent were college graduates.

Poorer, less educated people in Kentucky were also found to have increased levels of asthma and diabetes.

While the study also found that poorer Kentuckians have less access to health care, often forgo medical care due to the cost, and are less likely to have health insurance, it must be noted that this data was collected prior to the implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, which has since provided health coverage to more than 500,000 Kentuckians. The percentage of uninsured in Kentucky has dropped to 9 percent, compared to 20.4 percent in 2013, prior to the law’s implementation.

That being said, “one-quarter of consumers who buy insurance on their own still have problems being able to afford needed care,” according to a Families USA report.

“Simply having

health insurance is

no guarantee that

consumers can afford

to pay for health care,” the report said. “Health

insurance involves different types of costs that consumers

must pay out of pocket—ranging from a health plan’s

deductible to co-payments at a doctor’s office. These

expenses add up, and research has shown that even

nominal cost-sharing can deter people from getting

needed care.”

“Economic opportunity is the cornerstone of getting people jobs and employment. That then requires good education. Those two combined set the stage for people to pay more attention to their own health and the health of their community,” Dr. William Hacker, former state health commissioner and current health chair of Shaping Our Appalachian Region, said at a recent advisory council meeting. SOAR is a bipartisan, nonprofit effort to improving the economy of Appalachian Kentucky.

The importance of getting families out of poverty was also noted by Dr. Terry Brooks, executive director of Kentucky Youth Advocates, in response to the 2014 Kids Count report, which ranked Kentucky 32nd in economic well-being.

“Here’s the bottom line from this year’s report: If we as a commonwealth want to get serious about improving the lives of our children, there is one overriding and persistent challenge: poverty,” Brooks said. “You can’t talk education or health without talking family economics. And we can begin to tackle persistent poverty only when economic well-being policy stops being political and starts being about the common good.”