How Medicaid came to cover 1 in 3 people in Ky., 1 in 5 in U.S., and how it could be changed despite health bill’s failure

|

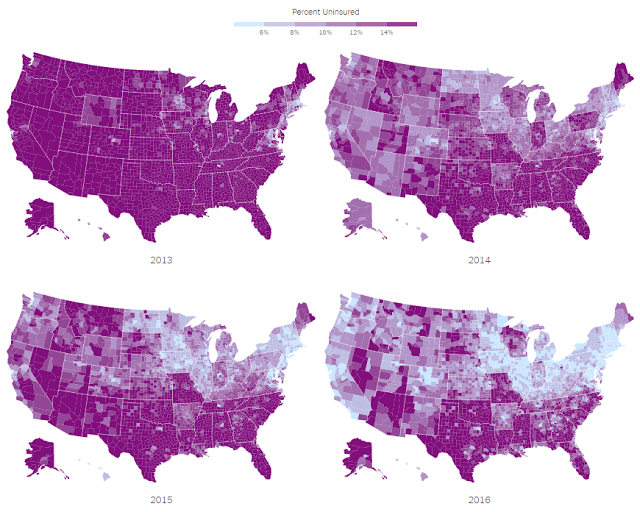

| Medicaid is the main reason many more people have health insurance, especially in Kentucky. These New York Times maps are interactive, with county data. For the interactives, click here. |

The failure of the Republican health-care bill in the U.S. House put a fresh spotlight on the importance of Medicaid, the federal-state program that covers nearly one in three Kentuckians, one in five Americans, four of every 10 U.S. children, almost half of all births and two of every three people in nursing homes.

“While President Trump and others largely blamed the conservative Freedom Caucus for that failure, the objections of moderate Republicans to the deep cuts in Medicaid also helped doom the Republican bill,” Kate Zernike, report Abby Goodnough and Pam Belluck of The New York Times. “Even some conservatives . . . expressed concerns about the number of Medicaid recipients who would suffer.”

Medicaid grew much larger with passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, because it allowed states to expand the program to people with incomes up to 138 percent of the federal poverty level, about $34,000 for a family of four, with the federal government paying the cost through 2016 and states’ share gradually rising to the law’s limit of 10 percent in 2020.

The bill would have stopped enrollment under the expansion, so Medicaid rolls would have gradually declined as people went off the program and people who formerly would have been eligible could not enroll or re-enroll.

“It also would have ended the federal government’s open-ended commitment to pay a significant share of states’ Medicaid costs,” the Times notes. Because Kentucky is a poor state, federal taxpayers cover about 70 percent of traditional Medicaid costs. The national average is 60 percent.

|

| Gov. Matt Bevin’s Medicaid idea resembles one Vice President Pence enacted as Indiana governor. (Courier-Journal photo) |

No matter what happens with efforts to write another bill, Kentucky, other states and the Trump administration are likely to make changes that would trim Medicaid. The administration is expected to approve Republican Gov. Matt Bevin’s request for a waiver that would allow the state to charge small, income-based premiums, impose work-related requirements on able-bodied adults who aren’t primary caregivers, and make other changes.

Then-Gov. Steve Beshear, a Democrat, expanded Medicaid in 2014. Most people on the expansion work, but Bevin argues it is a disincentive to work, because employment would push some beneficiaries’ income beyond the eligibility limit.

Almost two-thirds of Americans said in a 2015 poll that they were on Medicaid or had a friend or family member who was, but because “many of its beneficiaries are poor and relatively powerless, Medicaid lacks the uniform, formidable political constituency that Social Security and Medicare have,” the Times notes. Still, polling on the issue by the Kaiser Family Foundation has never found more than 13 percent of U.S. adults who want to cut Medicaid spending.

“The conventional wisdom that there’s a great deal of stigma attached to this program does not bear out,” Kaiser pollster Mollyann Brodie told the Times.

Trump said in his campaign that Medicaid should not be cut. But he endorsed the House Republican bill, which was the party’s third major attempt to end Medicaid as an open-ended entitlement, the Times notes: “The first was under President Ronald Reagan, the second was in 1995,” in conjunction with welfare reform. “But this was the first time Republicans tried it while the controlled the White House and both houses of Congress.”

Medicaid started in 1960 as “a small program to help the states treat the needy, as a way to stave off proposals for Medicare,” the Times reports. When the Medicare-Medicaid bill passed in 1965, the latter half “almost escaped notice” and wasn’t even mentioned in the Times. Congress gradually expanded it, sometimes as part of deals to cut Medicare, gradually decoupling Medicaid from the welfare system, said former Rep. Henry Waxman, D-Calif.

Then states began to expand the program, because “The assumption you could afford health insurance if you were an able-bodied adult was not true” any more, due to rising health costs, University of Chicago Professor Colleen Grogan told the Times. It reports, “Now that the law known as Obamacare has survived the effort to repeal it, more states may choose to expand Medicaid.” The Washington Post reported likewise.