59 percent of Ky. adults have experienced at least one adverse childhood experience, linked to physical and mental health issues

|

|

Robert Wood Johnson Foundation illustration

|

Kentucky Health News

Many health-care providers have started looking at adverse childhood experiences when assessing their patients’ poor health because ACEs have been linked to risky health behaviors, chronic health conditions, low life potential and early death, and because 59 percent of Kentucky adults were exposed to at least one such experience as a child.

“There are things that happen to us early that make a huge difference in what happens to us as we get older,” Dr. Connie White, senior deputy commissioner for the Kentucky Department of Public Health, said at a March 22 meeting in Frankfort to prioritize the state’s top health issues.

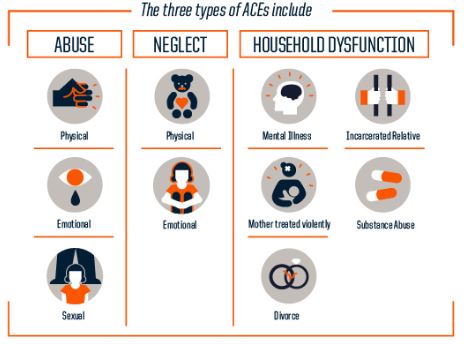

ACEs are “potentially traumatic events that can have negative, lasting effects on a person’s health and well-being, including early death,” the department says. They include: physical abuse, sexual abuse, emotional abuse, physical neglect, emotional neglect, a mother being treated violently, parental separation or divorce, substance misuse within the household, mental illness in the household, and having an incarcerated household member.

White said it is important for children to live in a secure and nurturing environment during the first two years of their life because this is when brains are “hard-wired” for social-emotional development. But she said it is just as important for children to grow up in an environment that is free of traumatic events.

“It’s like building a house,” she said. “There is a foundation, and if you don’t start out with a very good foundation you are going to have a very unstable house.”

White said children who grow up with ACEs often struggle academically and behaviorally.

White said children who grow up with ACEs often struggle academically and behaviorally.

“These children have impaired memory, they have an inability to concentrate, it’s hard for them to stay seated, it’s hard for them to follow directions, they are constantly on edge, they are easily provoked and they are impulsive because of the toxic stress they have at home,” she said. “So these are children that are hard to deal with and I think the folks in our judicial system see these children all the time.”

At least one program in the state is working to inform educators on how to deal with ACEs. The Louisville program, called the “Bounce Coalition,” provides training on ACEs and resiliency to school staff and out-of-school activity providers in two Jefferson County public schools and will soon expand to three more and more than 500 YMCA programs this spring. This work, funded by a grant from the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky, is expected to evolve into a state model for addressing ACEs.

Research shows that the impacts of ACEs don’t end in childhood. The original ACE study, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Kaiser Permanente, found a clear scientific link between many types of childhood adversity and the adult onset of physical disease and mental health disorders.

The report said that as the number of ACEs increases, so does the risk for things like alcohol abuse, chronic disease, poor work performance, financial stress, domestic violence, suicide and poor academic achievement, to name a few. It also found that people with six or more ACEs died nearly 20 years earlier than those without ACEs.

Kentucky just started surveying for ACEs on its 2015 Behavioral Risk Factor Survey. The poll found that 59 percent of Kentucky adults had experienced one or more ACEs, 64 percent had two or more and 17.5 percent had experienced four or more, higher than any other state that surveys for ACEs.

Kentucky’s survey found similar results as the original national study, showing that the more ACEs a Kentucky adult had, the more likely he or she was to have smoked cigarettes, use and abuse alcohol use, bear or father children in their teens, attempt suicide during adolescence, have chronic depression as an adult, have impaired work performance, and have many chronic diseases.

“So this is an issue that I think we all need to be cognizant of so that we are not asking people what’s wrong with you, but we start to think what happened to you and how did you get where you are right now,” White said, noting that it is never too late for a person to learn how to be more resilient.

She added: “We can’t go back and fix what’s happened, but we can work on trying to figure out where people are coming from and how we can help them be better.”