If you have a Kynect policy, or are buying one, shop around to get the best deal; prices and tax credits change each year

“More than 70 percent of people currently enrolled in Affordable Care Act health-insurance-marketplace insurance can find a 2015 health plan offering the same level of coverage at a cheaper premium,” reports Jason Millman of The Washington Post, citing a report from the federal Department of Health and Human Services. The report says 80 percent of current enrollees could likely “find a health plan with a monthly premium lower than $100 after tax credits are applied.”

The reason, according to the department, is that premiums for the benchmark “silver” plan, the second-lowest cost plan in each area, are increasing an average of 2 percent this year. The benchmark plan is used to calculate how much a tax credit a consumer can receive on any plan, and it may have changed in each area, causing a change in the tax credit in 2015.

Most people generally stick with their health insurance, even if it means passing up a better deal, and the Obama administration “is begging” people to shop around to make sure they have the best plan available to them, Milliman reports.

Shoppers have until Feb. 15 to pick a health plan, but they only have until Dec. 15 to choose a plan for coverage starting Jan 1.

The health-reform law is working well, but “One fundamental challenge remains: If Obamacare is to succeed in holding down premiums over the long run, it needs consumers to shop around,” rather than treating health insurance like finance or a utility, and falling victim to “consumer inertia,” James Surowiecki writes for The New Yorker magazine.

|

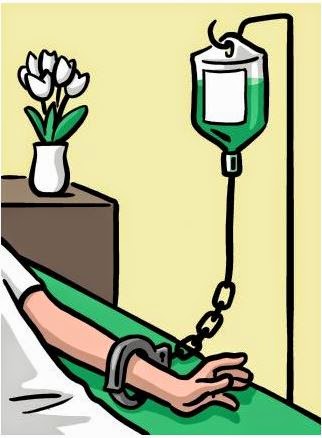

| “Consumer inertia” in health care New Yorker illustration by Christoph Niemann |

“People have no difficulty comparison-shopping and changing allegiance when it comes to, say, automobiles or consumer electronics. Companies in those markets face huge pressure to keep quality high and prices low,” Surowiecki writes. “But there are also markets where consumers tend to stick with the same choice forever, even though switching could save them quite a bit of money. Energy bills are a classic example. We’ve long been told we can save money by leaving incumbent providers for newer upstarts, but the vast majority of us haven’t. Economists call it consumer inertia, and you can see it in many fields, including banking, credit cards, and health insurance.”

Surowiecki elaborates on several factors that cause this inertia: the complicated and confusing nature of health insurance, which often offers complex and multiple options; the time and energy it takes to do enough research to make an informed switch; the added complexity of factoring in subsidies and taxes that comes with Obamacare; and the greatest one, the very real fear of changing doctors if you change insurance.

This inertia benefits insurance companies, making it easy for them to raise prices, Surowiecki writes. He offers this example: If you have a storage unit, you may well have been lured by an attractive monthly rate, only to find that it soon started rising by significant increments. (What are you going to do? Move all your stuff?) “Similarly, even though there are lots of affordable new Obamacare plans this year, many of last year’s are raising premiums substantially,” he writes.

Surowiecki says Obamacare both limits and encourages this inertia. It limits through the influx of new customers who pay attention to price, pressuring insurance companies to keep premiums reasonable. He also suggests that people with lower incomes, as many using the law are, will scrutinize the price of their insurance. But the automatic renewals of insurance built into the law, for those who don’t change plans, encourages the inertia.

One study found that “fully informed” consumers saved a couple of thousand dollars compared with those who were less well informed, as long as they are confronted with the information, Surowiecki reports.