Sen. Rand Paul makes inaccurate remarks about virus, vaccines and ‘naturally acquired’ covid-19 disease, FactCheck finds

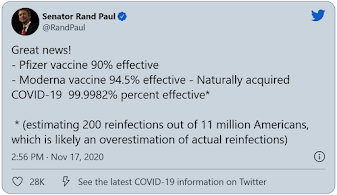

U.S. Sen. Rand Paul’s Nov. 17 tweet

—–

U.S. Sen. Rand Paul of Kentucky is being taken to task for a series of remarks he has made about the novel coronavirus, vaccines and immunity. FactCheck.org, a nonpartisan, independent unit of the Annenberg School of Communication at the University of Pennsylvania, found several inaccuracies in his statements.

Paul made his claim in a Nov. 17 tweet in which he listed interim efficacy figures from two ongoing vaccine clinical trials and then provided his own calculation of the “effectiveness” of natural infection with the coronavirus.

In a follow-up tweet, the Kentucky Republican shared a link to a New York Times article about a new unpublished study that found evidence of some immunity to the coronavirus in most people for at least six months. He commented: “Why does the left accept immune theory when it comes to vaccines, but not when discussing naturally acquired immunity?”

Paul, who has previously spread misinformation about childhood vaccines, has inaccurately argued during the covid-19 pandemic that parts of the U.S. have reached herd, or community, immunity because of pre-existing immunity to other coronaviruses. Herd immunity is when enough people in a population are immune to prevent spread of the disease.

Public-health experts, however, have said that threshold is still a ways off — and that allowing the virus to spread uncontrolled would lead to many needless deaths. A better approach, they say, is to stave off the spread of the virus until a vaccine is widely available.

A Paul spokesperson told us that the senator was not suggesting that immunity through natural infection with covid-19 is better than getting immunity from a vaccine, but rather, “highlighting research that says immunity is real.”

We were directed to subsequent tweets, including one in which Paul said he was not “arguing against vaccines” but that covid-19 patients “can celebrate immunity if lucky enough to survive,” as well as Paul’s support for alternative options to speed along access to covid-19 vaccines.

Still, the efficacy figure Paul provides for natural covid-19 infection isn’t accurate. And the juxtaposition of the numbers implies a kind of superiority of natural infection over vaccination — a dangerous notion, given that contracting the virus poses a serious risk.

As University of Florida biostatistician Natalie Dean pointed out in response to Paul’s tweet, “The key distinction is that vaccines are a safe way to achieve immunity. Getting sick with covid-19 is inherently unsafe. We would never ever tolerate a vaccine that carried even a fraction of the risks of natural infection.”

While Paul purports to offer a precise percentage for how “effective” natural infection is relative to vaccines, experts told us that the comparison is premature and faulty.

The efficacy figures for the vaccines come from interim results released in press releases by the two companies, Pfizer and Moderna, and refer to the ability of the vaccines to prevent symptomatic covid-19 infection in phase 3 trials. (The day after Paul’s tweet, Pfizer announced additional data reflective of the full trial, which showed 95% efficacy.) But the number for natural infection is a broad-strokes calculation Paul made based on reinfections.

“We don’t really know how many reinfections there have been,” virologist Angela Rasmussen said in a phone interview, adding that many reinfections have not been confirmed and that efficacy of naturally-acquired immunity “isn’t a thing.”

“It’s just really ridiculous to try to use the way that efficacy is calculated in clinical trials for vaccines and apply that to epi[demiologic] data across the entire population,” she said.

Dr. Paul Offit, director of the Vaccine Education Center at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and a member of the Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee, agreed.

“Clearly, there are people who can be reinfected. As a general rule, it’s usually more mild reinfection,” he told us. But, he added, “most people aren’t tested, so you don’t really know who’s getting reinfected and who isn’t.”

It’s true that reinfections so far appear to be rare, which bodes well both for a vaccine and for people who may have immunity as a result of infection. But no one knows yet how the immunity from each will compare.

Most vaccines do not offer quite as good protection from a pathogen as a natural infection will — but of course, a person has to survive or suffer through the infection to get that future protection, sidestepping the entire function of a vaccine. It’s therefore largely irrelevant whether or not vaccine immunity is superior to that from natural infection.

There are some instances in which a vaccine does elicit a better immune response. That’s the case for vaccines against human papillomavirus, or HPV; tetanus; Haemophilus influenzae type b; and pneumococcus.

Whether covid-19 will be one of them remains to be seen. Rasmussen said it was possible, but still hypothetical at this point. “We don’t really know. We only know that these vaccines typically induce levels of neutralizing antibody that are comparable to the higher levels of neutralizing antibody that’s been observed in convalescent patients,” she said, referring to the type of antibody that can prevent cells from becoming infected with the virus.

Based on the performance of the shingles vaccine, Offit speculated that some of the later-arriving vaccine candidates that include powerful adjuvants, or chemicals that are added to vaccines to boost the immune response, such as those from Sanofi-GSK or Novavax, might be better than natural infection.

For both the vaccine and natural infection, important questions about covid-19 immunity remain.

“We do know that most people who get covid-19 do develop some kind of measurable antibody response, but we don’t know what that really means in terms of protection against either reinfection or whether you will mount protective immune responses upon a re-exposure,” said Rasmussen.

As a result, public health officials have cautioned that for now, even if people have previously contracted covid-19, individuals should still follow the standard recommendations.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, for example, advises all people, including those who have recovered from covid-19, to continue to physically distance, wear masks, wash their hands and avoid crowds.

Similarly, the CDC notes that it doesn’t yet know “if or when” it will stop recommending masks or physical distancing after vaccination.

This is in contrast to Paul’s assertion that people “can celebrate immunity.” In a Nov. 12 interview on Fox News, Paul used similar language and advocated that people drop these precautions.

“We have 11 million people in our country who’ve already had covid. We should tell them to celebrate,” he said. “We should tell them to throw away their masks, go to restaurants, live again, because these people are now immune.”

A huge question is how durable immunity will be. Although the study Paul highlighted suggests that most people will be protected for at least six months — and might mean they are protected against severe disease for many years — it’s still not definitive, and doesn’t mean that those timeframes will apply to everyone.

Shane Crotty, an immunologist at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology and one of the senior authors of the paper, noted on Twitter that the team observed a wide range of immune responses in people, including a lack of a measurable response in some people.

“That led us to speculate,” he said, quoting his manuscript, that “‘it may be expected that at least a fraction of the SARS-CoV-2-infected population with particularly low immune memory would be susceptible to re-infection relatively quickly.’”

The CDC, notably, has said that people who have had covid-19 may still benefit from a coronavirus vaccine. And some experts envision a future in which multiple vaccines are on the table for everyone.

“It strikes me as not unlikely that we will learn what the duration of protection is and people will need — whether naturally infected or vaccinated — to have booster shots over some period of time, once a year, once every two years, once every five years,” Barry Bloom, an immunologist and global health expert at Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, said in a press call.

In his tweet about the new immunity study, Paul also suggested that Democrats were somehow denying realities about immunity from natural infection.

“Why does the left accept immune theory when it comes to vaccines, but not when discussing naturally acquired immunity?” he asked.

Scientists, however, objected to Paul’s characterization.

“I don’t think anybody’s dismissing [immunity following natural infection]. I think what people are saying is, it’s a bad idea as a strategy for dealing with infection,” said Offit, who noted that 30% to 40% of the population could be considered at high risk for covid-19.

Both Offit and Rasmussen also pointed out that historically, there isn’t a lot of precedent for building herd immunity through natural infection.

“People were getting smallpox for millennia,” Rasmussen said, and “the herd immunity threshold was never really reached.”

The much safer way of getting to herd immunity is to use a vaccine instead, especially when multiple candidates are on the horizon.

“Trying to achieve herd immunity [without a vaccine] would result in hundreds of thousands more — if not millions — of unnecessary deaths and debilitating illness for millions more,” Rasmussen said. “So I think it’s not really right to talk about vaccine-induced herd immunity versus naturally-acquired herd immunity without mentioning the fact that one of them has a very, very large price tag in human lives and quality of life attached to it.”