One mother’s story helps show how recovery from addiction, difficult anywhere, is even harder in much of rural Kentucky

Megan Simpson works after group class at Living Clean transitional housing in Manchester. She recently completed peer support training and passed her certification test. She started as a peer support specialist in Corbin and is scheduled to go to court in April to regain custody of her three children. (Photo by Silas Walker, Lexington Herald-Leader)

—–

The continuing struggle of Megan Simpson of Manchester helps show the difficulty that rural and small-town Kentuckians have getting treatment for substance-use disorder.

Simpson’s story of addiction, treatment, relapse and recovery has been told in two long installments by Liz Moomey of the Lexington Herald-Leader. The latest appeared Sunday, along with a story by Moomey about the limited access that rural Kentuckians have to treatment.

She reports, “In many rural areas, resources are often few and far between to get treatment and return to life after recovery. Sober living housing is scarce. Transportation is limited. Childcare is sparse. Broadband internet for telehealth appointments or for virtual recovery meetings is unreliable.”

“Many people don’t have all those stars aligned and they have a very difficult path ahead of them,” said Matt Brown, Addiction Recovery Care’s senior vice president of administration, who “struggled with substance use disorder for 18 years,” Moomey writes. “He considers himself fortunate to have a wife who stayed with him through his addiction, an education and a job.”

Rural areas not only lack a choice of providers for counseling and treatment, there is a lack of anonymity in small towns, Moomey notes, quoting Brown: “Everybody knows everything.”

|

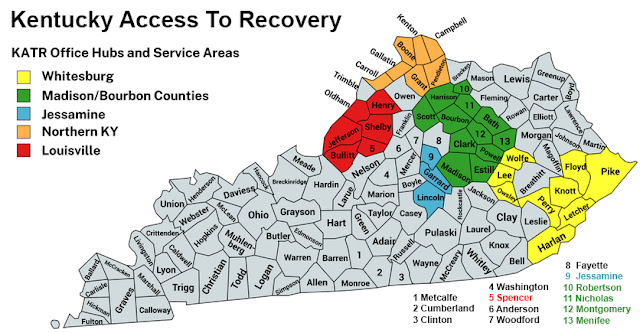

| KATR map via Herald-Leader, adapted by Kentucky Health News; to enlarge, click on it. |

Aaron Brown, a Western Carolina University professor who researches the issue, “said KATR wants to address the practical needs of rural Kentuckians that prevent people from accessing recovery,” Moomey reports. Brown said the types of jobs available and the benefits provided are more limited in rural areas. From his research on rural areas, good-paying jobs were often more taxing and didn’t always provide the option to take off work to participate in recovery opportunities.”