Kentucky does well in national comparison of premiums and tax credits in new health-insurance system

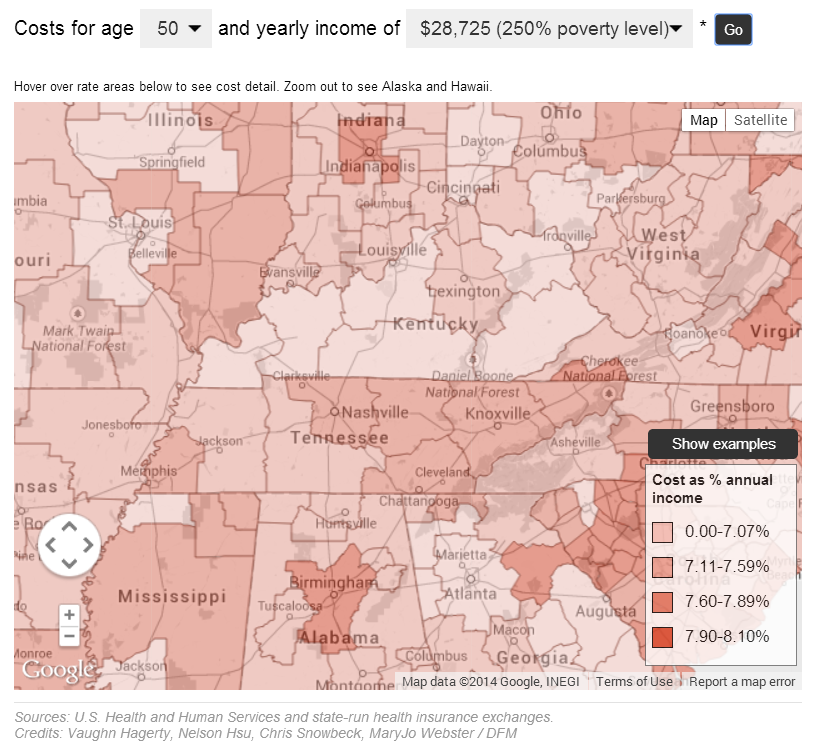

In more urbanized areas, where insurance competition is greater and prices are lower, smaller tax credits are needed, but more subsidy is needed in places with higher premiums—such as rural areas of the South. “Because there is so much geographic variation in cost, the government does have to pitch in a larger portion of premium in higher-cost areas to make coverage affordable,” said Cynthia Cox, a researcher at the California-based Kaiser Family Foundation.

Though some people feel that the law is unfair and that they don’t receive the tax credits as high as in other areas, the PPACA exists to ensure that “people at certain income levels pay no more than a set share of income to buy the midlevel ‘benchmark’ health plan where they live,” Snowbeck and Webster write. Some variation in price disappeared, though, because insurance companies can no longer refuse to cover people who have pre-existing health conditions, said Jonathan Gruber, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology economist who helped craft the law.

Coverage prices differ because of factors such as health status, cost of living and competition among insurance companies. However, though the same plan sells for $170 per month in Pittsburgh and $450 in areas of Georgia, federal subsidies based on income brign the latter cost below $300. “The tax credits can help us bring that premium cost down and say to people: ‘It’s now in the achievable range,'” said Tracy Brosius of the Wyoming Institute of Population Health.

Sometimes the tax-credit system actually allows people in higher-cost cities to pay less than those from lower-cost cities. “Assessing which consumers wind up with the ‘better deals’ can be complicated, policy experts say, because the lowest-cost silver plans available in different regions likely have different coverage details, such as deductibles and networks of doctors and hospitals,” Snowbeck and Webster write. Though some argue that the new system doesn’t offer incentives for regions that more provide more effective health care, Cox said “Insurers still have a financial incentive to keep premiums low to attract enrollees, particularly young enrollees who might not be tax-credit eligible.” (Read more)