State’s opioid-settlement money should be used for housing and transportation, other needs, speakers tell commission

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

More than 100 people attended the fifth town hall of the Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission to suggest how to spend the state’s $478 million settlement with opioid manufacturers and distributors.

Bryan Hubbard, executive director and chairman of the commission, told Kentucky Health News after the Oct. 26 meeting in Lexington that the recommendations were similar to earlier town halls and probably won’t change in the remaining three, to be held in Louisville, Bowling Green and Paducah.

“We seem to have good coverage when it comes to acute treatment within Kentucky; we’ve come a long way when it comes to making that available,” Hibbard said. “There’s a lot of work to be done when it comes to those things that people need to maintain recovery and to take ownership for their lives. Housing, transportation, second-chance employment opportunities, and the resolution of legal problems that continue to hunt down people down years after by have occurred, all of those things have emerged every place we’ve gone to.”

Half of the settlement funds will go to the state and the other half will go to Kentucky’s counties and cities. The county and city funds are to be used to support organizations that develop and implement programs to combat the opioid epidemic in Kentucky. The process to apply for a grant to fund such endeavors can be found at ag.ky.gov/OAAC. Hubbard said the commission had already received 102 grant applications through Oct. 25.

Asked how the commission will determine who gets the grants, he said, “We are going to sort applications into those areas that pertained to prevention, treatment and recovery. We will then match what are essentially the proposals to the needs. And we will figure out which organizations seem best ready and equipped to meet those needs and have deliberations and hand out money in accordance with those priorities.”

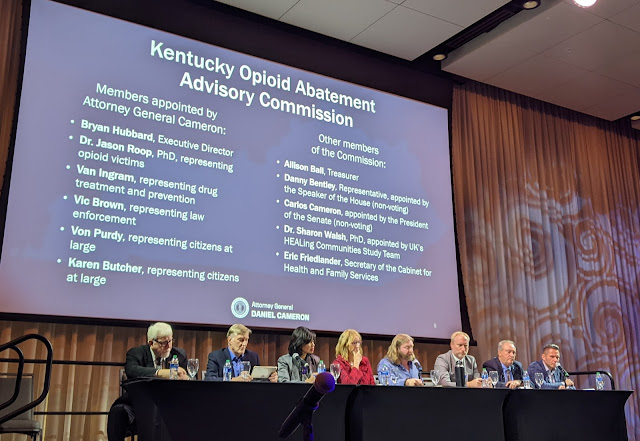

The commission, created by the legislature, has11 members, two of which are non-voting. The money will be paid out over 18 years with hopes of getting the first installment in December, Hubbard said.

“We’re going to be good partners to the cities and counties to make sure that we can be a resource of the allocation of the money to the areas where they are most needed . . . while also ensuring that we have quarterly financial reports, which verify and authenticate those expenditures for the intended purpose,” he told the Lexington audience.

The remaining town halls will be held in Bowling Green Nov. 9 and Paducah Nov. 29. The latest was held in Louisville Nov. 1.

The Lexington town hall lasted nearly three hours. About 30 people stood to tell their stories of addiction, recovery and loss before making their recommendations for how the settlement money should be spent. Here are some of their suggestions:

Need for safe and sober housing, call for better oversight

Several people talked about the need for safe and sober housing that is truly safe and sober.

“There’s a lot of them around, but there is not many of them that are dependable, that we know are safe and sober,” Thomas said. “I have had to tell people that I can’t find you a bed, only to get a phone call that they died.”

Commission member Van Ingram, executive director of the state Office of Drug Control Policy, asked Thomas what else needs to be done, noting that the state already requires recovery residences to be certified with the National Association of Recovery Residences.

To a big round of applause, Thomas said, “I think beyond the NARR certification would be to actually have some state regulations as to what qualifies as sober living.”

Larry and Nancy Blackford of Versailles told the story of their son’s overdose death in 2017. They too spoke to the need for safe and sober housing that is affordable, noting that there were times when their son was in housing where he “wasn’t comfortable.”

They also called for increased regulations for sober housing and treatment centers to ensure they are doing what they say they are doing and to ensure that they have medical staff on duty.

Need for more long-term recovery care

Several of the speakers talked about the need for more long-term recovery options, saying a 30-day treatment program is simply not long enough.

Charlotte Wethington told the story of her son Casey, who died 20 years ago from a heroin overdose at a time when there were few long-term recovery centers available and no laws that would allow them to keep a patient if they decided to leave. Further, she said that even when he was arrested, they couldn’t keep him if they wanted to leave.

After his death, Wethington was instrumental in getting “Casey’s Law” passed that allows families and others to file a petition to request involuntary, court-ordered drug treatment for their loved ones. The law has had varying success across the state.

Wethington’s request was for more long-term residential treatment. “I think we need to keep holding on to people, keep them in a safe place until their brain begins that healing process,” she said. “And we know that it’s going to take a while. It’s not going to be something that happens overnight. They need time.”

Need for pet care, transportation

John, who identified as a nurse practitioner who works in addiction care but did not give his last name, came with a list of needs: reducing stigma, more mental health practitioners, eliminating some restrictions on prescribing the treatment drug suboxone, and more transportation and housing, which he said are the “two biggest barriers we run into in this population.”

He also spoke to the need to provide pet care for people who are seeking long-term, in-patient treatment, calling this “a major problem that patients perceive as barriers” to treatment.

“Nine times out of 10, when I’m talking to a patient about inpatient treatment or getting higher levels of care, they are desperately worried about what’s going to happen with their pets,” he said. “It is a major problem.”

One man called for mobile methadone clinics to bring drug treatment and medical care to people who are houseless, noting that many people with drug addictions do not have access to transportation.

An infectious-disease doctor said lack of transportation is a huge barrier for his patients with substance use disorders who often don’t come back for follow-up care because of a lack of transportation. He also called for health care facilities that creates a culture that feels safe for people who use drugs. Further, he said there is a need for more adolescent treatment centers in Kentucky.

Other requests

Charles and Yvonne Byers and daughter Beth, who held her brother’s picture, told the story of son David, who died from a fentanyl overdose in August. He was 27. Their call was for efforts to stop the influx of the powerful opioid.

“We can’t bring David back, but perhaps we can bring our voice to this charge,” he said. “We must work together to solve this brutal attack on the children, on our friends, our loved ones, on our very way of life.” He closed by saying, “This is our son David and fentanyl killed him, because that’s what fentanyl does.”

One person asked for additional supports for grandparents who are raising their grandchildren because of the opioid epidemic. Several others pointed out that existing programs need financial support. Another asked for mental-health care for families dealing with addiction, and another asked that the commission only give money to programs that could prove their success with data.

In his closing remarks, Dr. Allen Brenzel, medical director for the state Department for Behavioral Health, Development and Intellectual Disabilities, summed up the recommendations as a call for recovery supports.

“We can do a lot with treatment, “he said. “But if we don’t support people in early recovery, we’re creating a revolving door.”