Frankfort power struggle, too few dentists and low Medicaid pay are all barriers to healing the pain in poor Kentuckians’ mouths

By Deborah Yetter

Kentucky Lantern

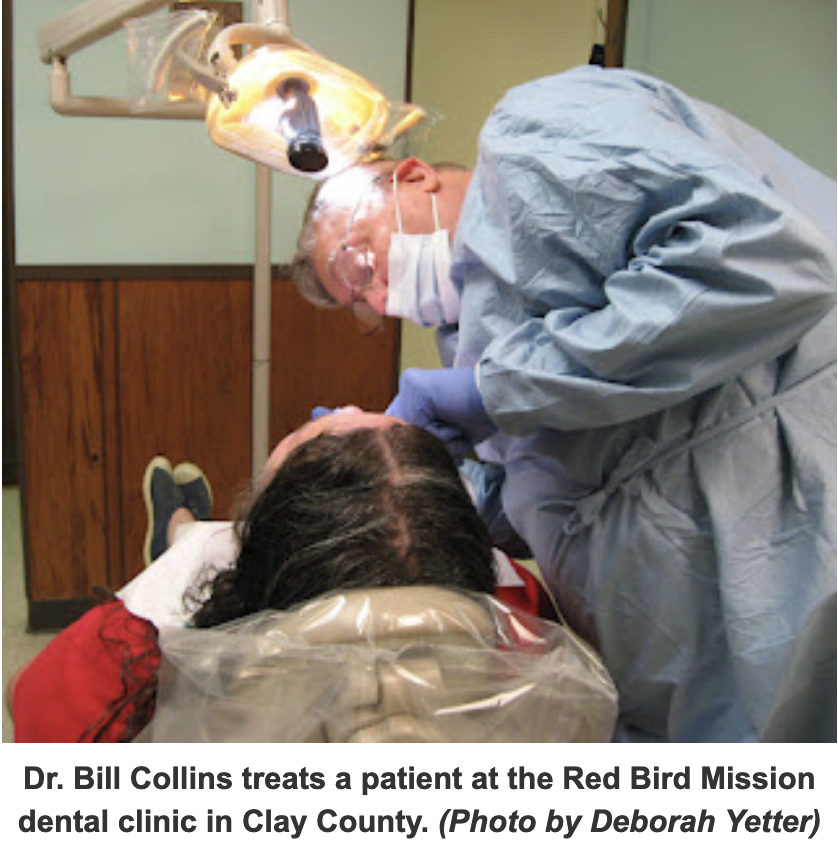

RED BIRD, Ky. — At the Red Bird Mission dental clinic in southeastern Kentucky, patients with few or no teeth now are eligible for dentures through an expansion of the state’s Medicaid dental services for adults.

“People are tickled to death,” said Dr. Bill Collins, the dentist at the United Methodist Church mission in a remote corner of Clay County. “We get patients who haven’t had teeth for 20 years.”

Dentures and other services newly covered by Medicaid have the potential to remake Kentucky’s image as a state of “toothless hillbillies,” said Collins, who has treated patients in the region for decades. “I hate that image.”

But a political fight in Frankfort over who has the power to enact the new benefits — that also expand vision and hearing services — could end the extra coverage advocates say is desperately needed.

Already the new benefits have started, stopped and started again amid a tussle between Republicans who control the General Assembly and Gov. Andy Beshear, a Democrat who enacted them Jan. 1.

“I’m not necessarily opposed to doing this,” said Rep. Derek Lewis, R-London. “There’s a lot of people in my district that could benefit from this. But the process matters.”

His southeastern Kentucky district usn’t the only one. The state ranks 49th in oral health and consistently ranks among the top states in the number of adults with no teeth.

“We really wish that the governor’s office and the legislature, working together, could find a way to get this done instead of being adversarial,” said Dr. Stephen Robertson, executive director of the Kentucky Dental Association.

Samone Gist, a Louisville woman suffering from multiple dental problems, says she just wishes someone would establish consistent, accessible dental care for people like her, who rely on Medicaid for health coverage.

A shortage of dentists — especially a lack of those who accept Medicaid, due to its notoriously low reimbursement rates — makes it difficult to find an appointment, health advocates say.

Recently, Gist said she managed to get one decayed tooth pulled but has others that need treatment. “I was in so much pain, it was unbelievable,” she said. “The pain is unbearable.”

Dental disease is linked to a host of health problems including infection, diabetes complications, heart disease and premature births — all significant health issues in Kentucky. It also is linked to addiction among those prescribed painkillers for dental abscess and decay, problems that too often send people to emergency rooms, advocates say.

Kentucky spends about $9 million a year in Medicaid funds on patients visiting the emergency room for dental pain, according to the Cabinet for Health and Family Services. In such cases, patients generally are prescribed antibiotics for infection and painkillers but don’t get dental care.

By contrast, the expansion of dental, vision and hearing benefits is expected to cost about $36.5 million a year, with $31 million covered by the federal government, which pays most of the state’s share of Medicaid. Beshear has said the state’s costs will be covered from savings in other areas in Medicaid.

Advocates argue that dental health, as well as good vision and hearing, also are essential in helping people get and keep jobs.

“Kentuckians need teeth. They need glasses. They need hearing aids,” said Cara Stewart, director of policy advocacy for Kentucky Voices for Health, a coalition of health groups. “It’s just a no-brainer.”

Gist, who recently attended a job-training program and is looking for work, agrees.

With bad teeth, “It’s embarrassing to do an interview or try to get a job,” she said. “It will definitely hold you back.”

There seems to be little dispute in Frankfort about the need for the expanded dental and other services for the 900,000 adults covered by Medicaid who could benefit.

But that’s where agreement ends.

For decades, adults covered by Medicaid were eligible only for an annual cleaning and tooth extraction. In a poor state where nearly 1.7 million people get care through the federal-state health plan, that led to inevitable results, said Robertson, the dental association executive.

“When the only benefit you’ve got is to have a tooth removed, that’s what the outcome is going to be,” Robertson said, adding that a recent study ranked Kentucky first in the number of toothless, older adults: “We’re number one”

So last October, citing the need, Beshear announced he was using executive authority to expand Medicaid dental, hearing and vision benefits for adults in the program.

Adults can now get dentures, fillings, crowns, and two checkups a year — as well as eyeglasses and hearing aids.

Republican lawmakers objected to Beshear’s move, saying he should have sought legislative approval. They passed Senate Bill 65 to stop the new benefits. But after the legislature adjourned, Beshear issued a new set of emergency regulations to again provide the expanded dental, vision and hearing services.

That restored the benefits but set up a new confrontation with Republicans who hold a supermajority in the General Assembly.

GOP lawmakers were swift to react, taking up the new version of the benefits at the May 9 meeting of the joint Administrative Regulations Review Subcommittee. They complained the new version looked much like the old version they had already rejected.

“I half expected Bill Murray to come to the table today because I feel like this is ‘Groundhog Day’,” said Senate Majority Floor Leader Damon Thayer, referring to the movie where Murray plays a TV news personality caught in a time loop. “The same thing kept happening over and over again.”

Beshear administration officials, including Medicaid Commissioner Lisa Lee, insisted the plan was within the bounds of a law that prohibits enacting regulations that have been rejected.

Besides, Lee said, with Kentucky’s abysmal ranking in oral health, it’s time to break out of the groundhog mode.

Since 2014, after Kentucky expanded access to Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act to include more low-income adults, the state has moved from 47th to 43rd in overall health rankings. “But we remain 49th in oral health care,” Lee said. “We have got to get something done here.”

Rep. Daniel Grossberg, a Louisville Democrat, agreed.

“Something has got to change,” he said. “We may be having an element of ‘Groundhog Day’ here but we’re living it over and over because neither side’s willing to give.”

Cabinet numbers show that the expanded benefits so far have resulted in dental, vision and hearing services for 196,000 people and about $12 million in payments to providers. About 4,000 adults have received dental services including 2,500 sets of dentures.

Republicans say they don’t necessarily dispute the need for those services, they fault the Beshear administration for failing to work with them.

“You kept coming back after we said no,” said Rep. Randy Bridges of Paducah. “We said no. We said no. You don’t want no. You’re going to do what you dang well please.”

Lewis, co-chair of the committee, said benefits aren’t the point. “I think every single person on this committee would be in favor of expanded dental services,” he said. “But our job on this committee is to protect the legislative process.”

The committee voted 5-2 to find the regulations “deficient,” with Democrats casting the two no votes, but the legislature can’t actually block them until it meets again in session in 2024 and enacts legislation to do so.

‘Last bastion of small business’

Meanwhile, Kentucky needs to work on other problems plaguing dental services throughout the state, especially in rural areas, dental officials said.

Medicaid reimbursement rates for dental services have not increased for 30 years to the point where costs of dental care exceed what the program pays, Robertson said: “For an office to decide to participate in Medicaid, they have to agree to operate at a loss.”

Of the state’s 3,200 licensed dentists, about 57% are signed up to treat Medicaid patients, but many either don’t accept them or limit those they see because of low reimbursement, he said.

The Medicaid reimbursement of $656 for dentures doesn’t cover the Red Bird clinic’s base cost of $1,100, meaning the nonprofit clinic has to make up the difference from other sources, Collins said.

The state’s latest proposed regulations include increased reimbursements for dentists.

The state also doesn’t have enough dentists and other staff, such as dental hygienists, to meet demand.

Even federally qualifed community clinics, long considered the medical safety net, have extended waits for dental care and few openings for patients, said Melissa Mather, chief communications officer for Family Health Centers in Louisville.

“I am for this Medicaid expansion big-time,” he said. “But when Jan. 1 hits, they’re going to come in here and stop it.”

When it comes to overall health, “The mouth is the gateway to everything,” he said. “We’re for finding the best way to move forward.”