28% of Kentucky students were chronically absent last year, up from 18% before the pandemic; national increase was even more

By Al Cross

Kentucky Health News

Twenty-eight percent of students in Kentucky schools were chronically absent from classes during the last academic year, compared to 18 percent in the 2018-19 school year, according to a national study done at Stanford University with the help of The Associated Press.

But Kentucky’s increase was less than the national increase, so much that its figure is now about the national average instead of above it.

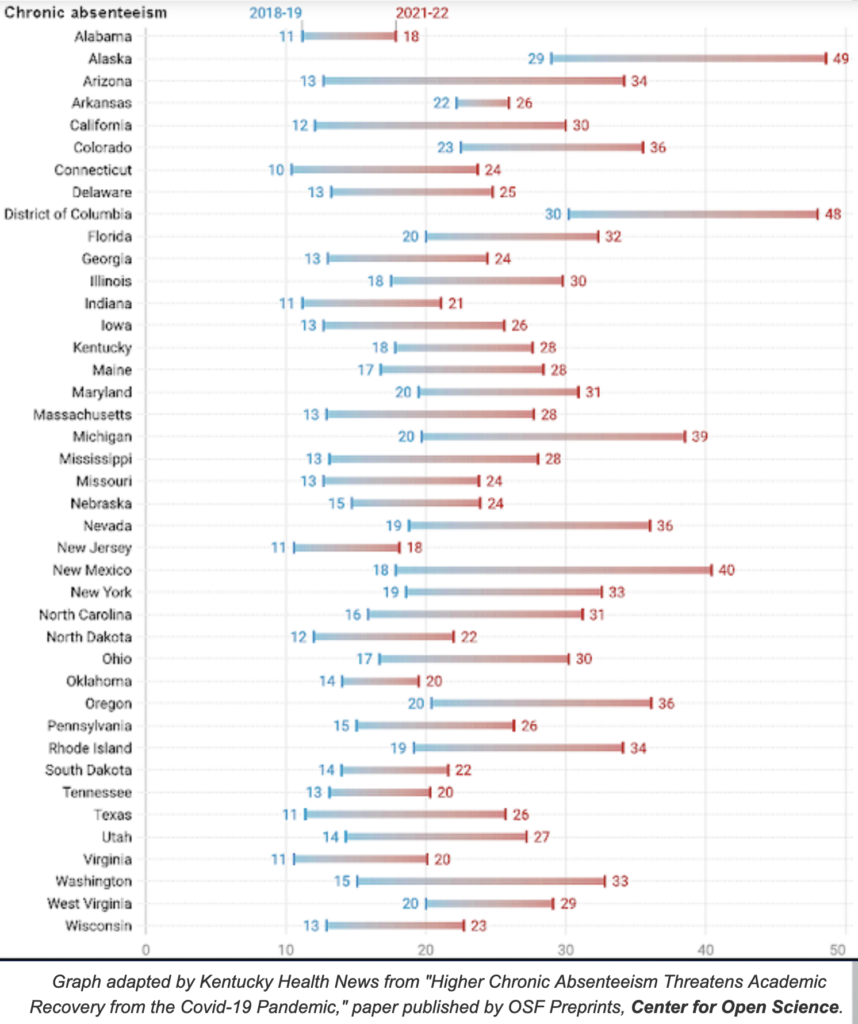

Kentucky’s rise of 10 percentage points was an increase of 56 percent. Nationally in 2018-19, 14.8 percent of students were chronically absent from school; in 2021-22, it was 28.3 percent. That increase of 13.5 percentage points was a rise of 91 percent from the last year before the pandemic.

“The large and broad increases in chronic absenteeism suggest many students are failing to re-engage in schooling as in-person instruction returned,” wrote Thomas Dee, the Stanford education professor who conducted the study.

“The data from 40 states and Washington, D.C., provides the most comprehensive accounting of absenteeism nationwide,” AP reports. However, Dee’s statistical analyses of the data were unable to find a pattern that explained the wide differences among the states.

Dee said he tested found little if any correlation between chronic-absenteeism growth and a state’s infection rate, its classroom masking policies, enrollment losses or differences in how “chronic absemteeism” is defined. Kentucky defines it as missing 10% or more of the year for any reason.

Kentucky’s chronic-absentee rate in 2018-19 was higher than the national average. Last year, it was about the same as the national average. (The report gave rates in whole percentage points, not tenths of points.)

The Economist reports possible reasons for increased truancy: “Having experienced remote learning, some students — and perhaps their parents — no longer think it essential or even worthwhile to sit in a classroom. ‘It’s the same thing as in the workplace,’ says a teacher in New Orleans. ‘Once you’ve gone down to only being there two or three days a week, coming back all five is hard.’ His classrooms are especially empty on Fridays, he says, so he avoids scheduling the most important lessons then. After the pandemic, people ‘started catering to their mental-health needs,’ says Tieshia Robinson, a principal at Chicago Collegiate, a public charter school in the city. For parents, that might mean allowing children who are unhappy at school to skip days. Pupils have also grown used to staying at home at the slightest sign of physical illness, says Greg Frostad of New Mexico’s education department.”

The highest 2021-22 chronic-absentee rates, 49% and 48%, were found in Alaska and the District of Columbia, which also had the highest rates in 2018-19, 30% and 29%, respectively. The third-highest rate, 40%, was in New Mexico; that was more than double its 2018-19 rate of 18%. Arizona’s rate also more than doubled, from 13% to 34%, the eighth highest in 2021-22.

Most of those leaders have high shares of miniority populations. “The pandemic growth in chronic absenteeism exacerbated pre-existing inequalities,” Dee writes, noting that the increases were larger “among economically disadvantaged students as well as Black students and Hispanic students.”

Other states where the rate doubled or more than doubled were Washington, 15% to 33%; California, 12% to 30%; Mississippi, 13% to 28%; Massachusetts, 13% to 28%; Texas, 11% to 26%; Iowa, 13% to 26%; and Connecticut, 10% to 24%. Dee reports that early figures for 2022-23 from Massachusetts and Connecticut show continued high absenteeism, and The Economist reports a like pattern in England and Australia.