Op-ed looks at ways to address loneliness, which is linked to a number of health conditions; Ky. is above average for loneliness

Kentucky ranks in the top 20 states for loneliness, which can involve far more than feelings of sadness from being alone. Research shows it is linked to strokes, heart disease, dementia, inflammation and suicide.

“It breaks the heart literally as well as figuratively,” opinion columnist Nicholas Kristof writes for the New York Times as part of a series titled “How America Heals,” aimed at finding ways to fix this problem.

The physical and societal harms that come from loneliness are so bad that America’s top public-health official, Surgeon General Vivek H. Murthy, issued a rare advisory with a framework to rebuild social connection and community in the U.S. in May.

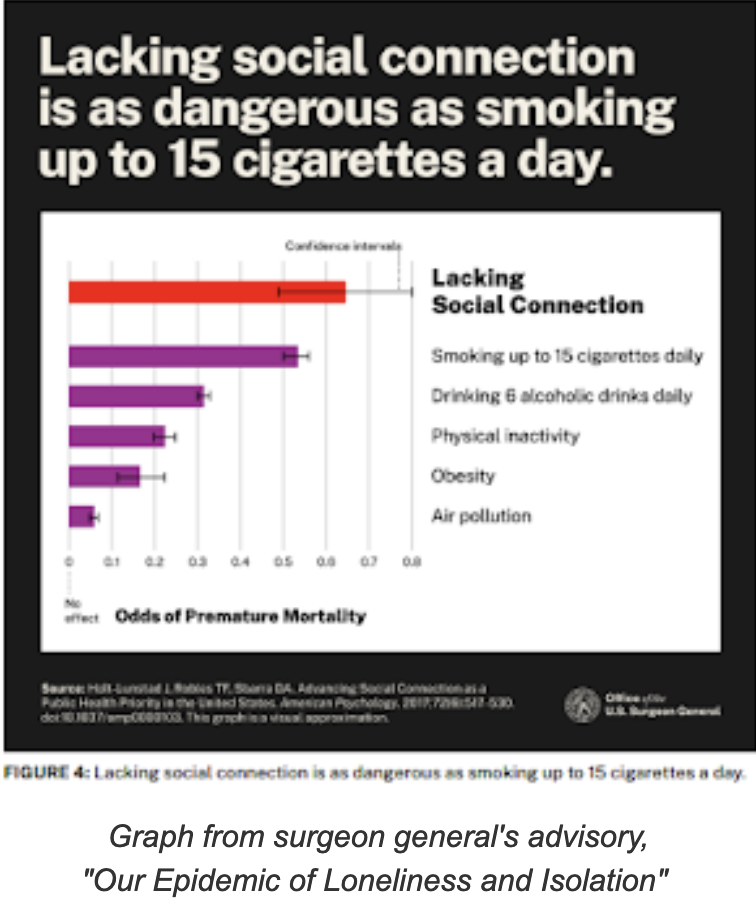

Loneliness is as deadly as smoking 15 cigarettes a day and more lethal than consuming six alcoholic drinks a day, according to Murthy. It is also more dangerous than physical inactivity, obesity and air pollution, he says.

Research also shows America has been growing lonelier. A majority of adults (58 %) report experiencing loneliness, according to a Morning Consult survey commissioned by The Cigna Group, a health-insurance company.

An Aging In Place study found that Kentucky tied with Arkansas for loneliness at 18th among states, with scores of 5.16 on a 10-point scale. Maine was first at 7.6, and Utah was best off, at 0.72. The study noted that more than half of Utahns identify as Mormons, which “may contribute to the low numbers of divorce and single-person households.”

The study looked at a range of factors, including the percentage of single-person households, number of people widowed, number of people divorced, searches for dating apps per 10,000 people and searches for friendship apps per 10,000 people, to determine which states struggle the most with loneliness.

Kristof writes that there are ways to build connections that bind us together and writes about some of those approaches taken by the United Kingdom, which he says “is the pioneer of these efforts, having established the post of minister for loneliness in 2018. Britain oversees public-private partnerships that collectively knit millions of people together with programs like nature walks, songwriting workshops and community litter pickups.” And, he adds, other countries have followed suit.

“That’s because if the researchers are correct, social isolation probably kills far more people in the West each year than terrorists and murderers, and it costs the public enormous sums in unnecessary health costs,” Kristof writes. “Countermeasures can make a huge difference: One review of 148 studies concluded that social connections increase the odds of an individual’s surviving over roughly the next seven years by about 50 percent.”

Kristof says he writes from troubles he’s witnessed: “More than one-quarter of the children who rode the No. 6 school bus with me in Yamhill, Oregon, have died from drugs, alcohol, suicide and other so-called deaths of despair. These pathologies are linked to social isolation.”

However, he notes that despite the economic devastation of during the Great Depression, mortality then didn’t rise but actually fell.” He attributes this to the “strength of community institutions — like churches, men’s and women’s clubs and extended families — that existed during that time.”

Ninety-odd years later, “Those community institutions have frayed,” he writes. “Now we’re on our own, and perhaps that’s why so many are also dying alone.”

Kristof says he recognizes that it’s not easy to rebuild such networks, but says we have to try, and offers some suggestions.

“The steps to tackle loneliness aren’t grand, high-tech or expensive. In fact, one of the strategies is simply to get people back into old-fashioned patterns like eating meals together, holding parties and volunteering to help one another out,” he writes.

He notes that the U.K. ministry has spent “some $100 million” to address loneliness since 2018, often to support local initiatives. One of those is a local, weekly family-style luncheon for women and children, many of them immigrants who struggle with English.

He says decline of religious attendance has left a gap in community building, but “church buildings can still provide a physical architecture for connections, even if the faith architecture has eroded.”

He also points to several community-wide events to combat loneliness, including an event held for King Charles’s coronation in May called “The Big Help-Out” to encourage people to come together and volunteer, and 6 million people, almost a tenth of the nation’s population, did so. “The response was so impressive that this may become an annual event,” he writes.

Why did loneliness increase? Kristof says the trends toward larger homes and longer working hours has left less time to share meals, and he notes studies that show social media has led to people being more lonely. Pets and talking robots have been suggested as solutions, he writes, but “It seems that there’s something to be said for friends who are living, breathing human beings.”

In his advisory, Surgeon General Murthy offered a strategy to address loneliness that begins with building up infrastructure that enables social connection: physical infrastructure such as parks and libraries, and social infrastructure to weave together volunteers or enthusiasts with similar interests.

Britain can serve as a model for this, Kristof writes. He points to a town that has has trained more than 1,100 volunteers to be “community connectors” who engage people and encourage them to join events or participate in programs. He also points to the idea of a “chatty bench” adopted in the U.K., Sweden and Australia, a bench with a sign encouraging strangers to talk to each other.

“Solutions to loneliness are like that — little nudges to encourage us to mingle the way we evolved to,” Kristof writes, suggesting that government do more: “President Biden, how about creating a senior government post analogous to a minister for loneliness? And mayors and governors, how about some chatty benches in American parks, along with volunteers deputized to bring us out for nature walks and sing-alongs?”