Rogers, citing treatment-bed increase, says E. Ky. is becoming U.S. drug-recovery capital; state has launched anti-stigma effort

By Al Cross

Kentucky Health News

Kentucky, especially its Appalachian counties, continues to be a hotbed of the opioid epidemic. But it is also a leader in fighting it, and getting people into treatment and recovery, the congressman who represents most of Appalachian Kentucky told the Kentucky Opioid Symposium Tuesday.

Rep. Harold “Hal” Rogers of the 5th District recalled a 2003 Lexington Herald-Leader headline that said Eastern Kentucky was the “nation’s painkiller capital” and said, After all the great strides that we’ve made from ground zero, and seeing the volume of treatment beds increase ten-fold over the last 20 years, I think it’s time for a new headline: Eastern Kentucky is now becoming the nation’s recovery capital, and it’s time to spread the message of hope in our commonwealth.”

Rogers said Dr. Nora Volkow, director of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, “tells me that Kentucky has had so much success that while other states appear to be making great gains, they’re merely catching up to Kentucky.”

Rogers, a Republican from Somerset, said the battle is “one of the few issues in Frankfort and Washington that is truly bipartisan,” and “shows what we can do when we put partisanship aside.” But that didn’t keep him from making two pointed compliments of Republican gubernatorial nominee Daniel Cameron, who as attorney general appointed most of the members of the Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission, which sponsored the symposium.

Rogers, a Republican from Somerset, said the battle is “one of the few issues in Frankfort and Washington that is truly bipartisan,” and “shows what we can do when we put partisanship aside.” But that didn’t keep him from making two pointed compliments of Republican gubernatorial nominee Daniel Cameron, who as attorney general appointed most of the members of the Opioid Abatement Advisory Commission, which sponsored the symposium.

The summit began Monday with a keynote address by Sam Quiñones, author of Dreamland and The Least of Us: True Tales of America and Hope in the Time of Fentanyl and Meth. He reiterated the message he has delivered before in Kentucky, that the solution for the opioid crisis lies in communities, not capitals.

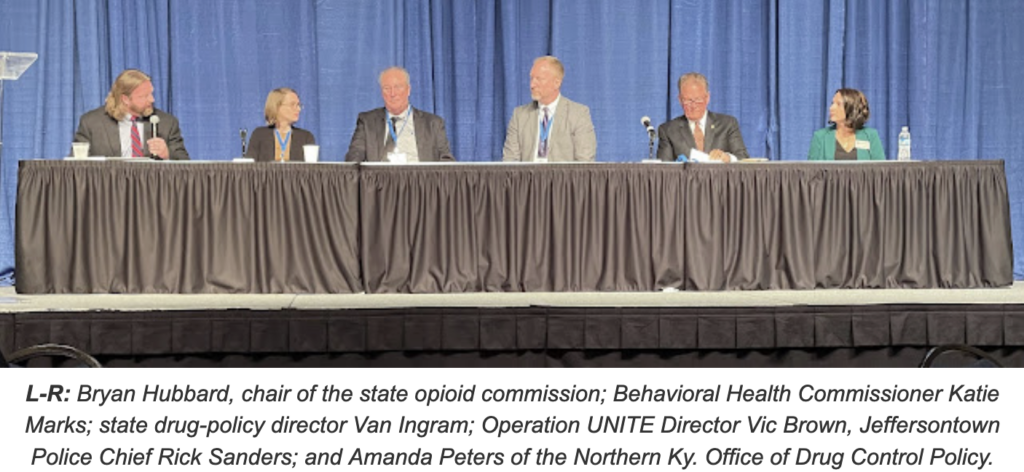

To that end, a panel discussion Tuesday about the course of the opioid epidemic included a local police chief, a regional drug-policy director, two state officials and the director of Operation UNITE, the Rogers-founded anti-drug nonprofit for Appalachian Kentucky.

Jeffersontown Police Chief Rick Sanders said he opened his department for addicts to seek treatment, then did likewise when he ran the state police. He said the idea met resistance from some officers “until we proved that it worked.” Now his departnent has three “embedded social workers.”

Sanders added, “Two of the biggest problems in law enforcement are addiction and mental health. We’re sending way too many people to jail that should be going to hospitals for treatment, and opening up those beds at the jail for people we really need to be afraid of.”

Amanda Peters of the Northern Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy said that as the region gained more treatment beds, it built a “long-term recovery pipeline” with employers and community organizations. She said that can also be done in rural communities, and cited the counties of Grant, Gallatin and Carroll as examples other rural counties could follow.

Van Ingram, director of the state Office of Drug Control Policy, said that 20 years ago, different regions of Kentucky had different drug issues, but “that distinction just doesn’t exist anymore.”

State Behavioral Health Commissioner Katie Marks outlined the basic steps to dealing with the problem, in succession: prevent initiation of drug use, prvent misuse, identify the need for treatment early on, provide treatment access and engagement, support completion of treatment, and sustain remission and recovery. She said the final step “is really important when we think about a community response.”

State Behavioral Health Commissioner Katie Marks outlined the basic steps to dealing with the problem, in succession: prevent initiation of drug use, prvent misuse, identify the need for treatment early on, provide treatment access and engagement, support completion of treatment, and sustain remission and recovery. She said the final step “is really important when we think about a community response.”

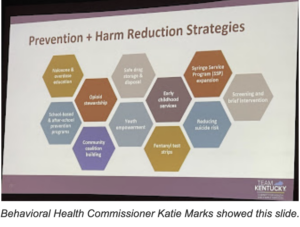

Marks also talked about specific stratgeies for prevention and harm reduction, including syringe exchanges, “vital infrastructure” that has still not been established in many Kentucky counties that the federal government considers at high risk for spread of disease among intravenous drug users.

Also, there needs to be more naloxone, the drug that counteracts overdoses, “in the hands of people most likely to witness an overdose or respond to an overdose,” Marks said, noting that the state is part of a national effort to determine how best to do that.

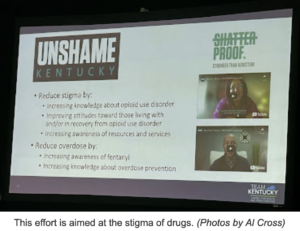

Marks promoted Unshame Kentucky, an effort to combat the stigma that many people still attach to the subject: “This is a community-driven, statewide anti-stigma campaign, developed by the voices of Kentuckians to say that we are going to unshame, we are going to reduce the stigma of addiction, of seeking treatment, of long-term recovery.”

Marks promoted Unshame Kentucky, an effort to combat the stigma that many people still attach to the subject: “This is a community-driven, statewide anti-stigma campaign, developed by the voices of Kentuckians to say that we are going to unshame, we are going to reduce the stigma of addiction, of seeking treatment, of long-term recovery.”

The state’s partner in the effort is Shatterproof, a national nonprofit that says it is dedicated to “revolutionizing the treatment system, breaking down addiction-related stigma, and supporting and empowering our communities.”