Your Local Epidemiologist says gun violence is public-health issue

OPINION By Katelyn Jetelina

Your Local Epidemiologist

On June 24, U.S. Surgeon General Vivek Murthy declared gun violence a public-health crisis. Many narratives immediately pushed back that this isn’t public health’s lane.

Let me say this loud and clear: Gun violence is absolutely in the purview of public health. And until society accepts it as such, we will continue to lose tens of thousands of Americans annually, leaving behind massive ripples in the community. Thankfully, momentum is changing.

Public health is everywhere—think seat belts, non-smoking areas, vaccines, airbags, clean drinking water, cleaner indoor air, food security, and cancer prevention. Experts are in health departments, nonprofits, government agencies, academic institutions, and the private sector. That’s because public health is most effective when combining science, education, policy, advocacy, and innovation.

Epidemiology, one subset of public health, is charged with finding patterns: Who is impacted? What predicts certain health outcomes? Because if it’s predictable, it’s preventable.

Violence epidemiology was born out of a case study a few decades ago, which showed that clusters of cholera in Bangladesh mirrored clusters of gun violence in Chicago. This meant gun violence wasn’t random; certain factors predispose a person or community. The field has grown to study suicide, child abuse, domestic violence, and, yes, gun violence.

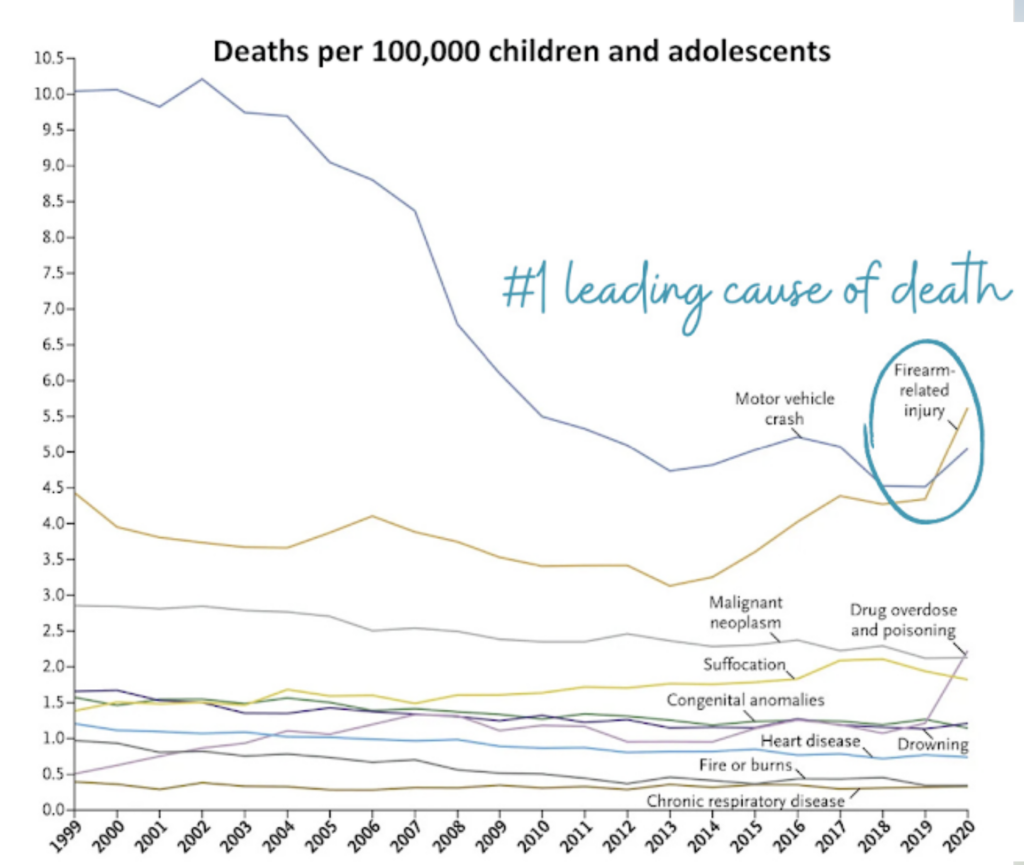

- Firearm injuries are the leading cause of death in children. It surpassed motor vehicle crashes in 2020 for the first time.

- 2 out of 5 homes have at least one firearm.

- 4.6 million kids live with unlocked, loaded gun.

- 1 in 3 youth suicides and unintentional deaths can be prevented by securing guns.

- 8 out of 10 children that used a firearm say it belonged to a family member.

These patterns suggest safe storage and education for parents, for example, could (and are) move the needle.

Suicides account for most gun deaths, followed by homicides. This is why some states have passed bipartisan legislation, like red-flag laws, to temporarily remove firearms from people who have been deemed a threat to themselves. It’s estimated one suicide is prevented for every 10–20 red flag orders issued.

Cause and risk are not uniform. Gun injuries and deaths differ by race/ethnicity, physical location, age, and many other factors. This suggests who and how we engage with matters to make an impact.

There are ripple effects. A single neighborhood murder can impact as many as 200 people in a community. Randomized control studies have shown that community-level interventions, like replacing vacant spaces with green spaces, break cycles of violence.

Finding answers has been a slow crawl. Although we’ve found some patterns, we’ve only scraped the surface. Progress has been plagued by an unfortunate series of events.

Rewind to 1993. A famous study published in the New England Journal of Medicine found that having a gun in the home increased the risk of homicide in the home. This set off a political domino effect, and three years later, Congress inserted the Dickey Amendment into the CDC spending bill. The provision stated, “None of the funds made available for injury prevention and control at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention may be used to advocate or promote gun control.” The language was unclear; the epidemiologist on the 1993 study famously said, “Precisely what was or was not permitted under the clause was unclear. However, no federal employee was willing to risk his or her career or the agency’s funding to find out. Extramural support for firearm injury-prevention research quickly dried up.”

This set gun violence research back decades, as it was completely reliant on nonprofits and philanthropy support. This is helpful but not enough to match the scope of the problem.

- Engagement from the bottom up. A plethora of public-health experts have partnered with groups directly impacted by gun violence. For example, working with gun owners and gun ranges to curb suicide or communities (see Cure Violence) to build solutions.

- Funding for research. In 2020 —for the first time in 25 years—our federal budget included $25 million for the CDC and NIH to research reducing gun-related deaths and injuries. This is a start, but to be clear, it’s estimated that we need $1.4 billion to curb this epidemic. (For context, NIH gets $6.56 billion allocated for cancer research.)

- State and federal initiatives. For example, the Office for Violence Prevention was established in 2023 to focus on key legislative actions. You may be surprised to hear that many policies have bipartisan support. Earlier this month, the office hosted 160 hospital executives and leaders to discuss the importance of using health system data to better understand patterns.

Gun violence is absolutely in the public-health lane. This is what we do. We’ve been able to do unimaginable things and save millions of lives by approaching problems with a public-health lens, like cigarettes and motor-vehicle crashes. Public health can help reduce gun violence in the U.S., and we will. But only at the speed at which society recognizes and supports it.