“Estill Medical. This is Madisyn. How may I help you?”

It’s a few minutes before lunch at Estill Medical Clinic, in Irvine. The practice is owned by nurse practitioner and Estill native Donna Isfort. It offers many services, but, like every other medical facility in the county, no obstetrician/gynecologist.

Isfort said, “Many, many of my patients at least have to travel anywhere from 30 minutes to 60, 70, minutes just to get to obstetrical care. There’s just not any here. We have no nurse midwives. . . . I do family practice, so I do a lot of women’s health at my clinic, but not prenatal care.

Estill County does have a hospital, but a spokesman for Mercy Health-Marcum and Wallace Hospital said it hasn’t delivered babies since 1986, not counting unplanned births in the emergency room.

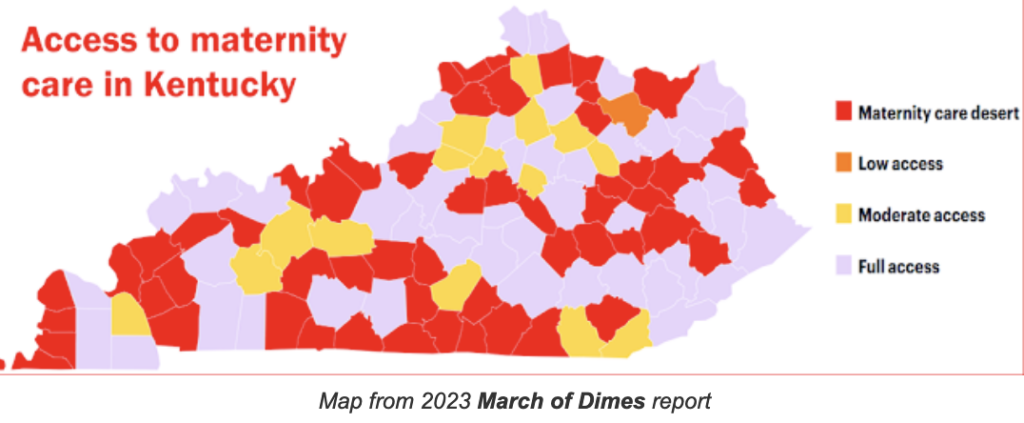

According to a 2023 report by the March of Dimes, women living in what some call “maternity care deserts” like Estill and several nearby counties must travel more than twice as far to get the care they need. Multiple studies conclude that greater distance puts women, expectant and otherwise, at greater risk.

Some think Kentucky’s maternity care deserts may spread. At a June 24 rally in Lexington to mark the two-year anniversary of the Supreme Court’s toppling of Roe v. Wade, second-year medical student Shriya Dodwani painted a bleak picture.

“The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education requires that OB/GYN residents have access to abortion training,” Dodwani said. “This isn’t about politics. It’s about ensuring that we have the comprehensive skills needed to provide the best possible care for our patients. Without this training in Kentucky, we’re left with no choice but to leave and pursue our education elsewhere.”

A week later, University of Kentucky HealthCare officials unveiled a plan that could help some women in rural areas. The outreach division of UK Women’s Health OBGYN announced they’d add services at 19 new sites, several in Eastern Kentucky, and expand telehealth services.

That sort of outreach could eliminate some of the long trips many women must make for routine care. Another program, funded in part by Medicaid and tobacco-settlement dollars, helps expectant and new mothers: HANDS, which stands for Health Access Nurturing Development Services. It’s available to all women during pregnancy through a child’s third birthday.

“We’re not coming in to look at your home. We’re not coming, you know, to tell you what t“o do, Talbott said. “We’re just coming in and giving you the information and helping you along with it.”

But Bingham says that when it’s time for her to leave for an OB-GYN visit, she makes the hour-long drive to Lexington.

The state Cabinet for Health and Family Services declined our request for an interview with the Department for Public Health’s director of women’s health.