Annual study of Ky. kids’ well-being looks at role of race, income and location; includes lots of county-level data, graphics maker

By Melissa Patrick

Kentucky Health News

The annual Kentucky Kids Count report has measured the overall well-being of Kentucky’s children for 26 years, but this year’s report digs deeper and looks at influences of family income, race and location on these measures, and finds that they matter.

“We need to continue to implement policies and practices that help all children, and in order to do that, we must face some uncomfortable truths,” Terry Brooks, executive director of Kentucky Youth Advocates, said in a news release. “One of those truths is that the ZIP code in which children live, the amount of money their family earns, and the color of their skin are pervasive and powerful influences on the childhood they will have and the future they can embrace.”

The report paints a vivid picture of what Brooks refers to: “We know that a toddler growing up in a rural southeastern Kentucky county will have different opportunities than a toddler growing up in the suburbs of Northern Kentucky, just like a young girl whose family is in deep poverty will have different life experiences than a young girl whose family is financially stable. And a black teenager will experience high school differently than his or her white peer.”

|

| Overall child well-being: Counties grouped from high to low |

The Kentucky counties with the highest overall child well-being are Oldham, Boone, Spencer, Woodford, and Ballard. Wolfe, Clay, Martin, Owsley and Lee counties scored worst.

The report notes that the 2016 report can only be compared to the 2015 report because of changes made last year. Click here to see the full report. Click here for the Kids Count Data Center for access to national, state and county data.

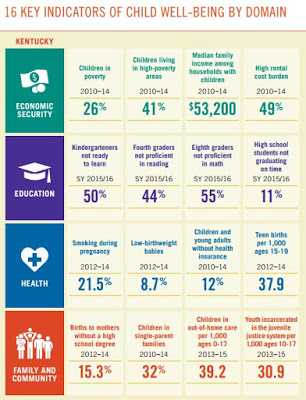

Most of the 16 indicators didn’t change much from last year, but the report found that income, race and location influenced every area of child well-being measured in the study. The report gives a detailed overview of these findings and offers solutions to address them.

More than one in four Kentucky children live in poverty: 26 percent. In several counties, the figure is more than 50 percent.

The report found that the state’s young children, those in Eastern Kentucky, and black and Hispanic children have a higher chance of living in poverty.

“There are several reasons why these groups face additional challenges in financial stability such as the high cost of child care for families with young children, job losses due to declining industries, and historical discrimination that prevented black and Hispanic families from building wealth and assets,” the report says. The study noted that race is a strong indicator of childhood poverty, with black and Hispanic children more likely to experience deep poverty, and to live in a neighborhood with concentrated poverty.

The report calls for “enhanced income and earning potential, building assets and rewarding personal responsibility through work supports” to help families find their way out of poverty. But it also lists specific legislation to decrease poverty, including paid family leave, a refundable earned-income tax credit, expanding access to child-care subsidies and limiting jail time for parents who have committed minor offenses to allow them to keep their jobs and support their families.

Education: rural-urban disparities

For more than 20 years, Kentucky has made gradual, steady progress on the percentage of fourth graders who are proficient in reading, which is important because studies show that a child who struggles to read proficiently in fourth grade is less likely to graduate. That trend continues, as the number of fourth graders not proficient in reading dropped to 44 percent in 2015-16 from 48 percent in 2014-15.

The rates varied greatly across school districts. The study also found that low-income children were half as likely as their higher-income peers to be proficient in reading by the fourth grade and that black and Hispanic students face greater barriers to reading proficiency.

The report also found that half of kindergarten students still don’t meet the standards that define “readiness to learn.” This measure is also influenced by income; 60 percent of low-income three- and four-year-olds in Kentucky are not in pre-school.

Young children in rural areas are less likely to attend an early-childhood learning program than those in urban areas, and “Research shows that children living in rural areas who start kindergarten with lower levels of reading achievement are more likely to fall behind their suburban and urban counterparts by third grade, even when controlling for household income,” the report says.

The report calls for communities to recognize and support parents as children’s first teachers, prevent summer learning loss and keep children healthy, which aids learning. It also suggests improved teacher training, more help for students and limiting discipline practices that remove children from the classroom. In addition, it calls for policymakers to increase investments in high-quality early learning programs, with a focus on reaching children who need it the most.

Fewer teen births, but smokers are a problem

The good news is that Kentucky’s teen birth rates continue to drop, to 37.9 teen births per 1,000 in this year’s report, compared to 40.6 per 1,000 last year.

But the report also points out that 8.7 percent of Kentucky’s babies are born with a low birthweight (less than 5.5 pounds) and that Kentucky has the second highest rate of births to mothers who smoked during pregnancy (21.5 percent), a known cause of low birthweight. Kentucky has the nation’s second highest smoking rate, 26.5 percent.

The report calls for tobacco-prevention programs for youth, smoking-cessation programs for pregnant women, and strong smoke-free workplace ordinances to reduce the rates of low-birthweight babies.

“Infants born at a low birthweight are more likely to face short- and long-term health complications and are 25 times more likely to die within their first year of life than those born at a normal weight,” says the report, adding that it is “also associated with impaired cognitive development, which impacts educational success, regardless of socioeconomic status.”

In Kentucky, the percentage of low-weight babies ranges from a low of 5 percent in Carlisle County, on the Mississippi River, to a high of 14 percent in Lee County, with the highest rates found in Eastern Kentucky. Babies born to low-income mothers are also more likely to have low weight.

The Kids Count Data Center can display comparative historical data for up to seven counties. Here’s a multi-line graph of births to smoking mothers in the Lake Cumberland region since 2004-06.

The graph shows that all seven have all exceeded the state average of births to smoking mothers, that Russell County has always led the group of seven, and that its rate has gradually declined since a jump a decade ago.

Family and community: crime and dropouts hurt

The report found that more than one in 10 Kentucky children have lived with a parent who has served time in jail or prison, the highest rate in the nation.

It also found that over the past 10 years, the share of Kentucky children whose head of household has at least completed high school has steadily increased. However, in 17 counties, at least one in four births was to a mother who did not complete high school.

“The more education parents have, the more likely their children are to be prepared for school, to succeed academically and complete high school by age 20, and the less likely they are to be born at a low birthweight, engage in unhealthy behaviors, and become a teenage parent,” the report says.

The report noted that adults in rural areas have consistently had lower educational levels and are more likely to be poor, regardless of education level, than those in urban areas; low educational levels are strongly linked to low incomes; and black and Hispanic children in Kentucky are more likely to live in a family where the head of household lacks a high school diploma.

The report calls for Kentucky to utilize a two-generation approaches that address both the needs of parents and children to help them attain needed educational levels and increased economic stability. It also called on workforce development efforts to provide benefits that help parents improve their skills and education.

Brooks said: “For kids in Kentucky, there are reasons why place, income, and race matter. Those reasons have been imbedded in us for years, and it is going to take time to change policies and attitudes to give every child a chance to thrive. We must learn, grow, and move forward together. It’s going to take all of us. Kids Count brings us the facts. Let’s face the facts and grow together to make Kentucky the best place in America to be young for all children. Our kids deserve no less.”