State drug-control policy office’s legislative package will include putting overdose incidents into prescription database

Kentucky Health News

SLADE, Ky. — The executive director of the Kentucky Office of Drug Control Policy said Friday that his office is working on a legislative package that includes putting overdose incidents into the state’s electronic prescription drug monitoring program, and offered a comprehensive overview of the problem, saying it will take 20 years to solve.

“We hope to be releasing a 2017 plan very shortly,” Van Ingram said at “Covering Health: A News Workshop,” sponsored at Natural Bridge State Resort Park by the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues and the Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky.

|

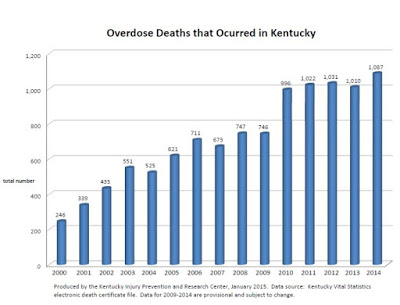

| Ingram’s PowerPoint presentation had many such charts and graphs. For a copy of it, click here. |

In 2015, 1297 Kentuckians died from a drug overdose. This was up from 1,087 in 2014 and up from 246 in 2000.

Ingram said approximately 28 percent of the 2015 overdose deaths had heroin in their system and approximately 34 percent had fentanyl, and most of them had a combination of drugs in their system.

“Almost every time you’ve got heroin, you’ve got a benzodiazepine also,” he said. “What a person generally dies of is drug toxicity.”

He added that 56 percent of the people who died from an overdose in 2015 had an opioid prescription written in the prior 6 months to their death, 33 percent had a current opiod prescription and 21 percent had an overlapping opioid or bezodiazepine prescription at the time of their death.

“They really need to know whether or not that person has had an overdose incident,” Ingram said of his offices plans to include this data in KASPER to better help physicians in their prescribing.

Ingram said that while there has been some decrease in heroin seizures in the state, fentanyl is on the rise.

“And that’s a trend that I predict will continue,” he said, noting that the “profit margin is amazing” for this drug, with dealers making up to $1.6 million dollars for a $6,000 investment or up to $6 million if they have the ability to create fake pills.

“This is a business model that is not going anywhere,” he said.

DEMAND, SUPPLY AND TREATMENT

Ingram said that while the United States has only 5 percent of the worlds population, it uses 99.3 percent of all hydrocodone combination products and 82 percent of the oxycodone.

“We lose 129 people in this country every day. That’s a small commuter airplane crashing every day. If we had a plane crashing every day, do you think we’d figure it out? . . . Of course we wouldn’t have anyone lobbying to keep plane crashes going. There are people lobbying to keep this number here. And they are a powerful lobby,” Ingram said. “If we don’t change these numbers nothing in this country changes and this opiod epidemic goes nowhere. We’ll just keep throwing Band-Aids on it.”

Ingram noted that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that providers only prescribe a three to seven day supply of pain pills after a procedure. He also said we need to start using opioids as a last resort for pain, that reimbursement rates must change to allow providers more time for evaluation and that reimbursement rates must also include alternative treatments for pain. And just as importantly, he said that we as a society have to stop wanting a quick fix for pain.

Ingram said the federal government has finally taken notice of this problem, but that he wished they had paid attention to Hal Rogers back in 2004 when “he was running up and down the halls telling everybody, but nobody would listen.” We need to “lay groundwork with good policy” that will make an impact over time, it took 20 some years to create this problem and it will likely take 20 more to solve it, he said.

Ingram pointed out that the solution to the opioid epidemic is greater than just saying, “Why don’t these people quit?” He explained that because of how opioids affect the brain, people who are addicted to them need the drug, just like we need food and water. And because of this, we need every available resource to treat it, including: medication assisted treatment, peer led recovery, intensive outpatient treatment and residential treatment.

“We need it all,” he said.

HISTORY

Ingram said it is important to recognize that conditions leading up to this “perfect storm” of opoid abuse have been in the making for the last 20 years.

He pointed out that it began with Purdue Pharma’s marketing campaign for OxyContin, which was heavily marketed in Appalachia. He noted that Appalachia had eight of the top ten zipcodes for the highest number of opioid prescriptions between 1998 and 2000.

“Appalachia was ground zero for this entire epidemic,” he said.

Ingram said the increase in lobbyists pushing for increased treatment of pain;The Joint Commission’s decision to establish pain as the fifth vital sign; and the decision to tie hospital reimbursements to patient satisfaction surveys, which asks patients if their pain has been adequately addressed, also contributed to the current problem.

In addition, he extended the blame to individuals wanting quick fixes for their pain; physicians who over-prescribed them; and the health insurance industries poor reimbursement policies for alternative treatments to pain.

Further, Ingram said the problem has been exacerbated by the introduction of abuse deterant formulas for pain pills; an increase in intravenous drug use; the increased awareness of prescribers; and the drug cartels recognition and response to the demand.

“All these things come together to form the perfect storm that we have today,” he said.

ADDITIONAL DETAIL

|

| Age of Decedents from overdose deaths in 2015 |

Ingram also pointed out that most people who overdosed in 2015 were between the ages of 45 and 54 (372), followed by 35-44 (341) and then 25-34 (288).

“This is not just a young person disease,” he said. “These are people who have probably had an opioid use disorder for a decade or longer.”

Ingram noted that the 2015 anti-heroin bill increased access to treatment, enhanced penalties for major drug traffickers and increased access to Naloxone.

He said the “Good Samaratin” provision of the law, which allows a person to seek medical help for an overdose victim and stay with them without being charged, was already “making an difference,” noting that the first months of 2016 were looking “a lot better than they did last year.”

“My early prediction on this is that this is making an impact,” he said, “I think more people are calling”

He also said that since the state has increased access to Naloxone, 1200 pharmacist are now trained to dispense it and that there are 300 locations dispensing it across the state. He added that the ODCP has recently launched an interactive website that connects zipcodes and counties with the closest places to get it.

Ingram recognized that syringe exchanges remain controversial, but said that after learning about them, he now considers himself the “poster boy for syringe exchange.” He pointed out that a lot more happens at needle exchanges than just the exchange of dirty needles for clean ones, including, medical treatment, HIV and hepatitis C testing and counseling.